Of Canada’s government-created problems, the poor state of some backcountry trails is not a major one. It affects thousands of people rather than millions and ruins vacations rather than livelihoods, safety, and society. Getting outside is good for you, physically, intellectually, and spiritually, so there are real consequences, but not quite as bad as the day-to-day Canadian experiences of unemployment, wage stagnation, price increases, and societal collapse. Hiking is not, in any properly-calibrated order, a very big deal.

However, it’s an interesting one. Parks Canada might be the electorally safest part of our government. There are institutions like the CBC or VIA Rail which defenders call underfunded and critics want abolished; their are quangos like the Canadian Forces or health care which everybody promises to improve and nobody does. But Parks Canada, though certainly criticized, is as close to a universal National Good Thing as we get. Nearly everyone wants Parks Canada around. The Libertarians would sell it, but they’re the only ones. Even the separatists object to the “Canada” part, not the “Parks.”

Yet it is clearly going downhill. Nearly everyone seems to want protected wild places that Canadians can access, except sometimes those responsible for providing it.

There are many types of government malice, using “government” in the proper, wider sense. The judges who write our most important laws, the bureaucrats by whose whim anything ever happens, the array of cultural and financial interests whose power would be so much simpler to deal with if it was all or even primarily about money.

You would hope that Parks Canada exists to do the best it can. Resources are finite, it has to prioritize, and sometimes priorities to you and me are not priorities to the nation; that is unfortunate, but healthy. Nonetheless, while Parks Canada’s dollar stretches only so far, we suppose it wants to do its best with every dollar it has, and taken all in all the organization will want the best for the country.

Friend reader, the example of the Simon Creek bridge to Athabasca Pass in Jasper National Park shows it is not so.

Other examples could be used. Did you know, for example, that it is no longer practical to complete the historic Chilkoot Trail, or the world-famous Pacific Crest Trail, since Canada has stopped letting hikers cross the border?1 Did you know that in British Columbia it’s now common to close popular provincial parks for weeks or months at a time because tribes want them to themselves and BC Parks wants to encourage them? None of that is Parks Canada’s fault, but they are major issues that have nothing to do with money and everything to do with culture. They point to a trend.

Simon Creek is a watercourse in Jasper National Park which effectively separates the ordinary hiker from the historic and beautiful Athabasca Pass backpacking route. It is probably the single most dangerous river ford shown on an official trail map in this country: fast, opaque, deep, and long enough. In the fall it is possible on foot, in the sense that wardens and extremely experienced backpackers have done it, but it is way above the odds on what is otherwise a rather docile trail that families could manage given time.

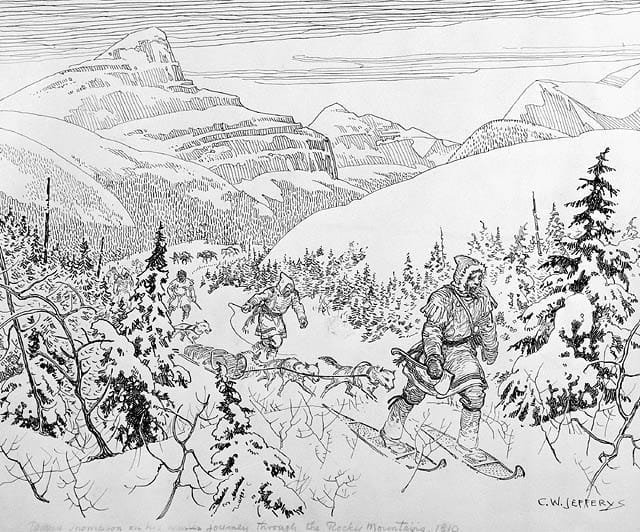

Athabasca Pass is a National Historic Site, honouring David Thompson’s opening the route in 1811 for the North West Company. The North West Company was the less famous but more enterprising rival to the Hudson’s Bay Company, formerly a department store and even more formerly a fur trading empire. Early in its history the HBC made its bones by, to oversimplify, sitting in their bases, having trappers bring them furs, and shipping them out of York Factory, their field headquarters on Hudson Bay. It was a harder and more adventurous life than that sentence makes it sound, but they generally objected to in-depth field work. This gave the North Westers their opening. The smaller, less-capitalized, but more enterprising North Westers took the trade to the trappers, blazing routes across the West and opening fur posts near where the trappers actually lived. Unsurprisingly the trappers preferred that, and the HBC reacted with hostility that blazed into violence.

In 1807, Thompson discovered Howse Pass, giving the North West Company access to what is now British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon from the east. Typically for Thompson, it did him no good at all. The Peigan Indians who lived there smelled commerce and demanded stiffer tolls than the usual plugs of tobacco, while the pass itself wound up with the name of a Hudson’s Bay man who only visited two years later.

Thompson was on his way home in 1810 when the NWC ordered him back west to find a new route from the prairies to the Columbia River, racing John Jacob Astor’s American Pacific Fur Trading Company to the coast. Thompson couldn’t, or wouldn’t, buy off the Peigans at Howse Pass, so he went north, knowing from his guides that another pass would exist if he was patient enough. The Athabasca is a tougher, higher pass than the Howse, but it was further from the threat of the Americans and, more importantly, free. From there Thompson became the first white man to boat the length of the Columbia River from the headwaters to the sea. The Americans got to the Pacific by ship two months before Thompson, and actually helped him home, but it hardly mattered: the North West Company won that particular fur trading war and though Thompson was long dead before his place in history was widely recognized, his is now a household name.

When the Hudson’s Bay and North West Companies were merged by government decree, it left the new HBC with the largest commercial empire in history and a more adventurous mindset. Their governor, Sir George Simpson, was no man to avoid a hard overland journey himself, let alone permit his subordinates to do so. The North West Company’s approach of getting near the sources of the trade had been proven sound, but the HBC was still centralized and corporate with one headquarters in London, one in Montreal, and one in York Factory. They would adopt the North West policy of far-flung trading posts, but those posts had to be managed by orders and personnel dispatched from Hudson’s Bay to Fort Vancouver2 and points in-between by the man they called the Little Emperor, ceaselessly driven and attentive to detail. To do so by sea, with York Factory icebound most of the year and Montreal scarcely better, was impossible. A regular overland route was therefore necessary, not to move furs or supplies, but commands and men.

Thus was born the famous York Factory Express which provided communications across the great expanse of Rupert’s Land. From Hudson’s Bay to the Pacific, two convoys a year followed Thompson’s route over Athabasca Pass. Even once the territory around Fort Vancouver was given to the Americans in 1846, the Company still had interests in British Columbia and Fort Victoria, and Athabasca Pass remained the most important overland route between the Canadian Prairies and the Pacific until the Canadian Pacific Railway. From a historical perspective, Athabasca Pass is one of the most important places in the western interior.

Since then Athabasca Pass has declined even recreationally. This was sped up by the 1964 Columbia River treaty dams and in particular the Mica Dam, which buries much of the old route under Kinbasket Lake and cuts the western side of Athabasca Pass off the road network. This coincided with the temporary downturn in backcountry usage across the mountain parks, as the horse-riding generations dwindled but lightweight, long-distance backpacking had not yet come of age. It was a very easy trail to skip, and skipped it was; as early as the 1980s, despite its bridges, Athabasca Pass was known for solitude.

But in recent years volunteers have been cutting out trail and building bridges on the British Columbia side. For the would-be thruhiker, the hardest part is arranging a boat across Kinbasket Lake, simply because few powerboaters will take the charter with waters at their September minimum. During higher water powerboats can bring hikers near Valemount, Revelstoke, or the Mica Dam site in style, and if Athabasca Pass was regularly visited year-round one of the outfits on Kinbasket Lake would take the money. Probably Athabasca Pass could never be Skyline. But it could be another South Boundary, relieving a strained trail system while giving Canadians one more walk to a piece of their common heritage.

The key barrier to crossing Athabasca Pass on foot today, then, is not really Kinbasket Lake, for that barrier will go away given a commercial excuse. Nor is it the hiking on the British Columbia side, which has been compared to a well-guided bushwhack but is bridged, signed, and provided with campgrounds, and where the Alpine Club of Canada clears every year or two. In the national park, by all accounts, the hike is pretty much fine, with the solitary and glaring exception of Simon Creek.

Watch the video where Stuart Howe and Scott Meadows failed to cross Simon Creek in early September 2022, or for that matter Marc of the Trail successfully fording it (twice!) in late September 2023. All three of these men are better outdoorsmen than most, and Marc in particular has a record of fording rivers others turn back from. Stuart and Scott looked hard for a safe crossing but did turn back, and very wisely; Marc made it but had a real good time, and late enough in the season that, as he found out, Athabasca Pass had its own set of hazards. At no time of year is Simon Creek anything but a crossing for the real expert. However, as Marc saw, once across the creek the Athabasca Pass trail is not too bad on the Jasper side, better than most half-abandoned trails in the park. Parks Canada keeps it open-ish for their own purposes on a roughly annual basis. The trail is a bridge away from being thoroughly accessible.

Only a bridge, but there are many demands for the park’s dollar and bridges aren’t free. But what if it was?

In 2022, a group led by Calgary’s Trevor Willson proposed to Jasper National Park that a bridge over Simon Creek be paid for and installed by the public, at no cost to the park. It sounds too good to be true but this was an extremely serious proposal. Willson is a professional engineer of formidable backcountry experience, including spearheading the restoration of the BC side of the Athabasca Pass trail. He has designed and built several backcountry bridges and had a concrete plan rather than just ideas. In terms of professional qualification and delivered achievements, he is hard for even trail bosses to argue with.

Willson’s first request, addressed to Jasper superintendant Alan Fehr in February 2022, was as moderate and reasonable as it gets. Funding had been obtained, regional tribes and governments were in favour or had no objection; would Parks Canada kindly expedite the bridge’s installation and move its camera visits earlier in the year for the convenience of hikers?

And at first all was well. Rejection came but it was prompt and civil, and one expects a certain amount of give-and-take with a national park. Jasper’s reply came with the feedback that “conducting an impact assessment, project management, construction and routine inspections and many years of ongoing maintenance” were burdens the park was not prepared to shoulder. So resolve the stated problems and, if parties are negotiating in good faith, the bridge gets installed.

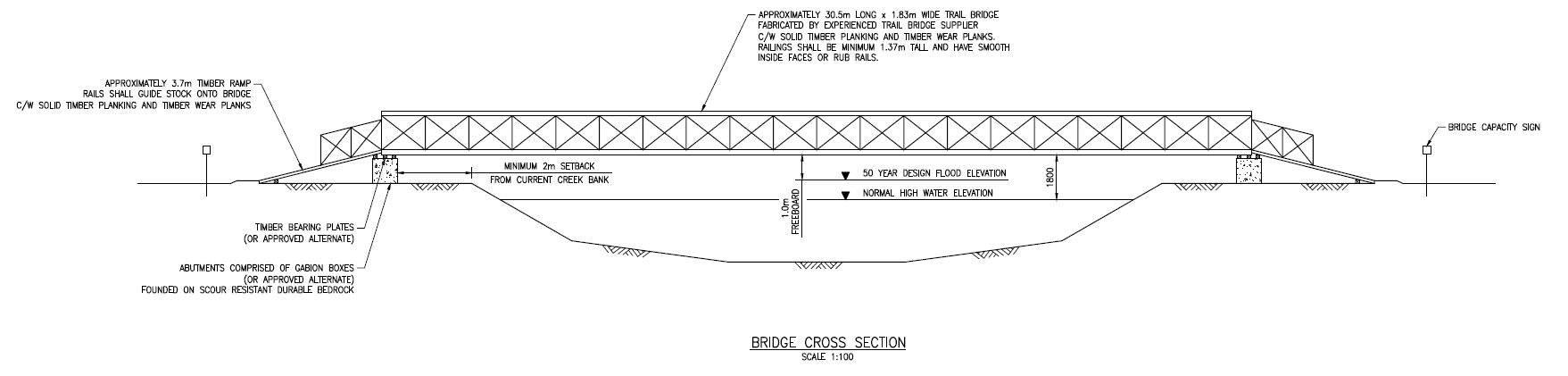

The second application did so. Willson and his friends spent eight months assembling their case in detail, while actually performing the required trail clearing on the BC side. Available online in two parts (part one, part two), the application was addressed to the Governor-General but came with the support of three area members of Parliament, two MLAs, the president of a wilderness group, and the president of both an area historical preservation society and tribal coalition. The forms were filled out, the project was costed, the budget was set, the funds were raised. The bridge itself, signed off by a certified engineer, was based off fielded-tested design that should fifty years with no disturbance of the creek. A heavy helicopter that would be in the area would lift the pre-fabricated bridge to the site at a significant discount. The project was costed at $336,527, down to food for the qualified volunteers who had already enlisted. The full amount was already pledged or expected, provided work could start in spring 2023 to exploit that bargain on the heavy helicopter (a charter would have more than doubled the budget). It’s an impressive document and proposes an impressive bridge, not some timbered span or humble, cheap suspension bridge like most but a blue-chip bridge for hikers and horses that would have been one of the two most elaborate in the Jasper backcountry.

The second rejection letter was a “no” that somehow managed to be both blunt and long-winded. The slender excuse offered was that while the bridge’s construction was funded, its eventual removal was not. At this point those familiar with the typical Jasper backcountry bridge removal, chucking the remains into the woods, were entitled to roll their eyes. Nevertheless a final effort was made, including raising $25,000 to decommission the bridge via a legacy and the cost of annual inspections by public donation, while observing once again that the proven and low-maintenance materials and design would make such costs low-risk anyway.

Even as a devil’s advocate, it’s hard to argue with this. The park had no reason to worry about the budget to install the bridge. Their risks were the opportunity costs of doing some paperwork. The proposal was serious and came from proven people with high-quality endorsements. Even if something goes wrong, when a bridge is to be prefabricated and delivered by helicopter, if the money turns out not to exist then neither will the bridge. The worst-case scenario was losing the bridge in sooner than fifty years and not getting the legacy to remove it after all, but bluntly that is no reason to turn it down, and if you’re worried about something particular you get it clarified in a hurry because this is a glorious opportunity with a time limit and the counterparty has proven willing to meet you more than halfway.

Jasper sat on that letter for six months. The cheap helicopter came and went. In July 2023, Parks Canada gave the inevitable flat no, making it clear they were not interested in any solution. “The bridge replacement,” they wrote, “may result in an increase in human use and impact in this remote area.”

Well, yes it may. That’s sort of the idea; that trails are for hiking, not for admiring on the map. Athabasca Pass has had human use and impact for centuries. It’s not virgin wilderness; a campsite commemorates the sawmill that had built and shipped out railway ties for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. The Canada National Parks Act states that “maintenance or restoration of ecological integrity, through the protection of natural resources and natural processes, shall be the first priority of the Minister when considering all aspects of the management of parks,” and as ever this first priority is loose when Parks Canada wants to build a massive frontcountry complex for the tour buses, and very rigid indeed when people want to open a trail to our national heritage.

One feels for Willson, who had given time and expertise to the nation, gratis, only to hit obstruction that began with passive-aggression and ended very deliberately. Whiling away the time while the cheap helicopter was available was a typically dirty trick. At the very least Jasper National Park could have saved time and heartache by saying “under no circumstances do we want regular people on Athabasca Pass” right away, but so clearly declaring your goals is foreign to the ways of bureaucracy.

In Jasper this is the rule, not the exception. At Parks Canada’s open houses in Jasper, there are regular questions about the backcountry. With equal regularity the answers, from superintendent Alan Fehr down, are bureaucratic and negative: one paraphrase I’ve heard is “no and stop asking.” The natural assumption is that it’s about money but the real problem is culture, and especially culture from on high that can only be addressed from higher channels still.

Allowing backcountry use is work. Not just in obvious ways, the trail clearing and bridge building and campsite maintenance. Those are relatively insignificant, and to a degree optional. In the case of Athabasca Pass, wildlife camera visits means the essentials are taken care of anyway. But a friendly culture in the park is mandatory, and harder to put into deliverable action items.

Tour buses are easy. You throw millions of dollars at problems then people buy trinkets, stay at nice hotels, and eat at fancy restaurants. Ecological megaprojects like caribou breeding programs are easy. The money flows like water, people see the necessity of the inevitable closures, and the work goes on with experts drawing steady paycheques and no pain-in-the-ass paying public to get in the way of your artfully-drawn plans.

The backcountry is hard. You need to institutionally know your trails in your bones, keep people informed of them and safe on them, and track priorities while reacting to reality’s surprises. You need to face the certainty that trails which had previously been little-regarded will grow through social media and word of mouth, and plans will have to shift. The Great Divide Trail once attracted single-digits of would-be thruhikers every year; now it’s in the hundreds. More and more people are visiting the South Boundary in Jasper, or the random zones in Banff, to test skills they acquired in the easier areas and escape the crowds. Backpacking is getting easier as equipment gets lighter and better, and is a cheap family-friendly vacation in tough times. It’s never been more popular, while the backcountry trails have seldom been worse. You need a culture that welcomes those challenges, and without it you’re Jasper National Park where, even when opening up a trail is cheap or free, it would be so much easier to just not.

Money is a problem, but hardly the most important. Trail clearing is often done anyway by passing wardens and can be handed off to relatively unskilled volunteers. Good campsites attract visitors, but experienced backcountry users get by without and some even prefer wilder camping. You can have Skyline, with bear lockers and three-hole throne toilets, and you can have the North Boundary Trail, with neither privy nor bear pole guaranteed, and people will enjoy both if they can. You can even have difficult river fords. They are common in the United States, including on wildly-popular trails, but only up to a point.

A successful example of Jasper backcountry culture is their horse program. One might think horses are an anachronism, and indeed helicopters, trucks, and improved communications have reduced their importance. Today Parks Canada’s mountain horses now have one year-round home from which horses are trucked when needed. However, most trails are impassible to ATVs and on these a combination of horses and helicopters is more economical than just helicopters. More importantly, people in the parks care about horses. Jasper has a dedicated equine boss who sees their value and advocates for them. When the fire of 2024 burned down some of Jasper’s horse corrals, little time was wasted rebuilding them. It’s a happy combination of a genuine public interest and people within Parks Canada who are passionate about it that keep the beancounters honest.

The parks need to be made to recognize that backcountry hiking matters, that it’s a good thing which can be safely done even with modest resources. Banff National Park, once the backcountry pariah of the Rockies, today keeps essential bridges in good repair, and has built dozens of cheap, cheerful 4×4-and-a-railing bridges across watercourses that might be trouble. Hundreds of their trail miles are first-rate, with elaborate campsites, and they’ve deregularized much of their backcountry where permits are required but camping is now random. There is plenty of challenge in Banff if you want it, but there are few examples of what is common in Jasper: extreme hazards on once-popular old trails.

How do you fix a culture? From below? Fat chance. That doesn’t happen. It has to come from above. But come it can, and come it should.

Calls to action

It is fair to say that Jasper National Park will not restore the backcountry on its own. In the immediate term that’s fair enough. Jasper’s recovery from the wildfire is, rightly, top priority, but then again, rebuilding trails could never be a project for 2025, but for 2026, 2027 and beyond, when the town is back on its feet and eager to welcome visitors such as those who would hike its legendary trails.

Hikers cannot seem to persuade Jasper’s bosses, and boy have they been trying. So the next thing to do is to persuade the bosses’ bosses.

-

Sign the Canadian Backcountry Trails Preservation Society’s online petition. A petition is a bellwether. Jasper’s backcountry woes are occasionally in the news, and it’s a great help when applying pressure to say that so many thousands of people have signed their names, urging improvement.

-

Write to your local member of parliament, especially if you live in a riding near the Rocky Mountains. Enter your postal code in the text field, select the current MP, and click the “Contact” tab for their e-mail, office phone, and mailing address. There is no constituency in Canada where nice parks, summer jobs for kids, and improved health aren’t popular. Make that point.

-

Write to the office of the Prime Minister and the office of the Leader of His Majesty’s Loyal Opposition. This is an unusually good summer for it. The new government’s Canada Strong Pass has been noted in the press as something of a fiasco, motivating camping in parks that have been reserved solid since January. The beauty of Canada’s wild places, and a desire for people to experience them, is virtually the only point of genuine patriotism which the government supports, but thanks to neglect (that did not start with this administration and would not have ended had it been defeated), it is getting more and more difficult.

The government’s priorities usually differ from of the ordinary Canadian. On big files, we all see how badly things are going. But backcountry trail usage is not a big file. There are no property values to protect, no companies to propitiate with low labour costs. The money involved is relatively insignificant, and the alignment with the government’s announced priorities obvious. Backcountry adventurers tend not to win high office, however, and as when a cabinet minister promises to tour Canada by train or something, it is obvious they literally don’t know how bad things are. They can be told. Cheap wins are the best of all, and if winning happens to lead to a politician helping Canada, what a happy coincidence.

- Specifically, both Canada and the United States now forbid border crossings at Chilkoot Pass, while the United States has always forbidden entry on the Pacific Crest Trail and Canada forbade it starting in 2025. I cannot imagine a problem with illegal immigration at Chilkoot Pass, which both starts and ends in the middle of nowhere; an issue on the PCT is barely more conceivable since it only starts in the middle of nowhere, but not issuing hiker permits wouldn’t solve it. It reeks of politics.

- That’s Vancouver, Washington, not Vancouver, British Columbia nor still Vancouver Island.