Ben Massey. Backpacking enthusiast, creator of this site, former writer of sports articles for several websites and one magazine, all-round handsome guy, and writer of his own blurbs.

1,757 words · Alberta, General topics, Hiking and backpacking "policy"

Everyone knew it was going to happen. The town of Jasper is… was? in a forest of trees killed by the mountain pine beetle, Dendroctonus ponderosae, over recent decades. Dry, hot summers, prone to lightning at all times of year, and filled with tinder. Now it sounds like the town is burned to the ground. Inevitable, but no less sad for it.

Naturally, blame is being cast. It’s the provincial government’s fault. It’s the federal government’s fault. It’s Parks Canada’s fault. The simple fact is that forest fires happen there, always have, massive ones, and when civilization came and started putting them out it did not eliminate the conditions but let them accumulate until they were past human control. Alberta, and Canada, are a long way from the only places to see this happen.

Vanity of vanities, says the Preacher,

vanity of vanities! All is vanity.

What does man gain by all the toil

at which he toils under the sun?

A generation goes, and a generation comes,

but the earth remains forever.

Never miss a ramble

Ben will hike to your inbox! New posts and nothing else.

1,626 words · General topics, Hiking and backpacking "policy"

On the night of September 29, Doug Inglis, Jenny Gusse, and their seven-year-old dog were killed in their tent by a grizzly bear on Banff’s remote Red Deer River.

There is no sign that the victims made any mistake. They were highly experienced in the outdoors. In that region of Banff National Park there are no bear hangs or lockers but bearproof food containers are mandatory and the park says they hung their food properly: if the park could tell that, it implies the bear didn’t get it. They carried bear spray, and emptied a can of it. They had a satellite messenger and the presence of mind to send an SOS, but the weather made it impossible for rescue by helicopter and even if it hadn’t, it would have taken a miracle to save them. While responding Parks Canada killed an older, underweight, aggressive female grizzly, and while the area of the attack is still closed to travel in case she wasn’t the bear responsible, the profile fits: it was late in the season, a cold spring has made for a bad berry crop, and bears jumping a camp is virtually always a predatory attack from an animal who is desperate for food before winter.

Small comfort, probably, to their families. It was the worst of all possible luck. Twitter comments were happy to write fan fiction about how it was probably their fault in some unspecified way but it wasn’t. It had probably been a couple days since the hikers had seen another human. Their ebooks were out. They were in their tent reading, waiting out crummy weather before bed. Any backpacker can see the scene in his head without having met either victim or knowing a thing about them besides where they were and what they loved to do.

2,811 words · Hiking and backpacking "policy"

I am a train enthusiast who hates flying. If I can reasonably take the train, I shall, and if it’s not reasonable I might do it anyway. Especially when hiking: you can’t fly with stove gas or bear spray, never mind checking your backpack and wondering if it’ll meet you on the other end.

This is not a politics post, but it starts that way: the National Post‘s Chris Selley recently reposted a July 2022 article about Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault’s rash promise to “cross the country by rail listening to people’s ideas about climate change,” reminding us of the Liberals’ 2019 campaign promise to “partner with VIA Rail to make [camping at national parks] accessible and affordable for more families.”

Neither trains to national parks nor a whistle-stop eco-tour happened, because Quebec-Windsor elites don’t know what the rest of Canada is. 95% of Canada has less frequent, less reliable, and slower passenger service than before the First World War. The High-Frequency Rail plan is peeling off the parts of Canada’s passenger network that get attention into a public-private partnership and the rest of the country will do what it can with a roll of quarters and 70-year-old train cars. When a politician says “I’ll take the train to Banff, how long could it be, six hours?” he’s not even lying, but ignorant.

Which is funny, because the trains are responsible for the mountain parks. The Canadian Pacific Railway built many of the trails in Banff, constructed hotels and tea houses, and literally opened Yoho’s Twin Falls with dynamite, but you’re not taking the train to Yoho anymore unless you work on one. In 1991’s The World of Lake Louise, one of Don Beers’ iconic Canadian Rockies hiking guides, he laments that “passenger train service is confined to weekends in the summer months. The trains stop only at Calgary, Banff, Kamloops, and Vancouver; the rail station at Lake Louise is closed.” In 1991 this seemed like an unbearable cutback; in 2023 we shout “RETVRN!”

You can still get to national parks by train. The adventurous can do a little more. Here’s what there is.

2,493 words · Gear, General topics, Hiking and backpacking "policy"

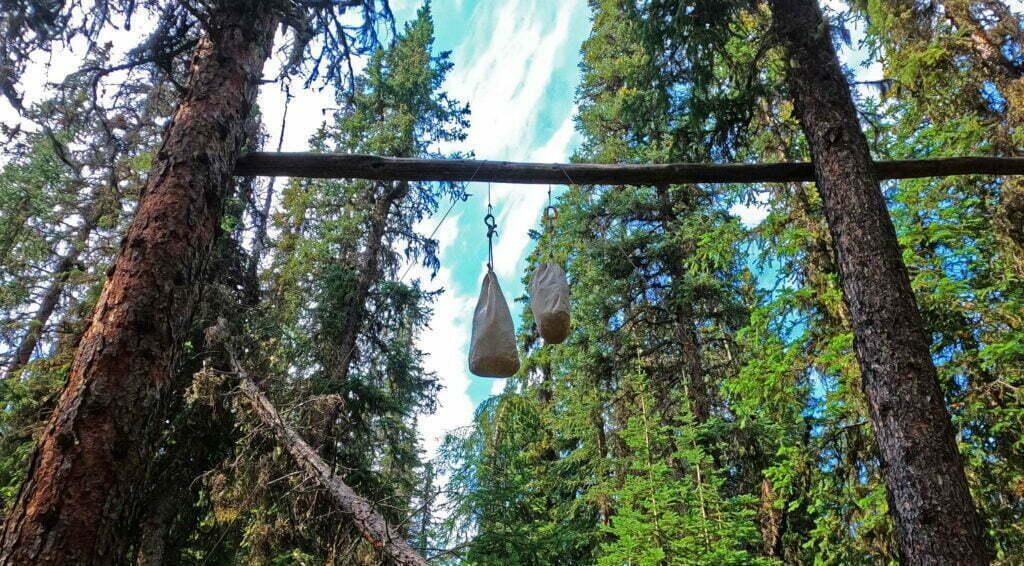

Bears are smarter than many people, and stronger than most. This past August another Problematic Bear at Garibaldi Provincial Park learned the knack of shimmying up BC Parks’ official bear hangs and bringing the bags down. Several hikers lost whole backpacks until conservation officers shot the bear.

This is the second-best recent British Columbia “bear defeating bear-proofing” story. The winner was at Akamina Creek in 2021, where a bear was caught non-chalantly opening bear-proof lockers right in front of several hikers (private video on the Great Divide Trail Hikers Facebook group). A few years ago Andrew Skurka shared a spreadsheet on Yosemite bears getting food from the portable hard-sided bear canisters. Most incidents involve user stupidity, but far from all. Given time, a cliff, a manufacturing defect, a slight fault in procedure, a plastic container weakened by UV, or just one that’s smarter than the av-er-age bear, that food is gone.

Traditionally this is when the author brags that he does it right. My food is all dehydrated meals and packaged snack bars, kept in an OPSAK resealable odour-proof bag that’s in turn tied inside an Ursack, hung on or stored in permanent infrastructure whenever available. Sure enough, a bear has never eaten my food (raccoons ate some once).

Except OPSAKs pick up odours from handling even before the openings fail, which they always do. Ursacks can be defeated when overfull, tied improperly, or a bear has four hours to work on the thing.

The author of this post is neither a bear expert nor highly experienced. In the wild he does what seems like it ought to work well enough. However, like most people who’ve lived in the world the past few years, he has a well-developed contempt for the narcissism of the expert. Responding to the Garibaldi incidents, the CBC quoted unnamed “advocates” whose words had no relevance to a bear climbing up the bear hang. Whenever a bear gets away with someone’s food wiseacres say “he probably didn’t do it right” and insist that if you follow these fourteen weird tips faultlessly every time you’re sure to be safe. It amounts to endlessly trusting the plan.

1,199 words · Alberta, General topics, Hiking and backpacking "policy"

Jasper National Park’s North Boundary Trail is a dream hike. From Celestine Lake to the Berg Lake trailhead in Mount Robson Provincial Park, it is much-discussed but not often-hiked. This year Thompson Valley Charters started a bus between Kamloops and Edmonton stopping at Mount Robson. I would have made it if not for Heat Dome, whose melt flooded these trails. BC Parks closed the Berg Lake Trail beyond kilometre 7 in August.

Also closed was a bridge over Twintree Creek, one of the few remaining on the North Boundary. Stuart Howe’s 2019 video shows horrible rushing blue-white water and Parks Canada has officially closed that bridge on pain of a $25,000 fine.

Berg Lake is closed for 2022 while under repair, but the North Boundary is long-neglected. Reservations are refused until September because Blue Creek bridge washed out in 2014 and they want hikers to wait until water levels go down. By all accounts Twintree Creek is tougher; it’s probably safest to consider the trail closed.

Would Jasper National Park lose a marquee trail for want of a bridge? Well, it keeps happening. The Fortress Lake trail into Hamber Provincial Park has been cut off since 2014 because of a washed-out bridge over the Athabasca River. The Athabasca Pass trail, leading to a National Historic Site of Canada, has been nigh-unreachable since the winter of 2016 due to a lost bridge at Simon Creek.

This is normally when an author bemoans Parks Canada’s budget and suggests the reader somehow vote our way out of it. Yes, Parks Canada should have the money far more than other things all politicians treat as higher priorities, but they ain’t quite broke. Earlier this year they built a 113-metre suspension bridge above Logan Creek on the West Coast Trail. A safe existing route has received a spectacular upgrade that will save hikers from what was once a morass of ladders and a shorter, still-memorable suspension bridge. The contract was valued at $840,122.

Bridges can be built, when they’re a priority.

1,113 words · General topics, Hiking and backpacking "policy"

Pandemics are boring. My home office in Vancouver, British Columbia looks out on a beautiful sunny day I am powerless to enjoy. Snowfields stare at me from the North Shore mountains while my snowshoes gather dust. Running around my neighbourhood only does so much; I miss nature. I miss the fresh air. I miss content for my hiking blog. I miss trees. I miss campsites and dehydrated food and reading a book on a lightweight chair and worrying about the rain and putting on three layers of jacket as I finish up the last camp chores while a gentle white light swings placidly within my tent. I miss being sweaty and stinky for days on end and not caring. I miss it all.

On the list of problems in the world today this is, to be sure, not number one. We’re all in the same boat and I think we all understand why we’re doing it. At risk of sounding controversial, if we all died of coronavirus that would be sad. Probably all of us who can are social distancing in ways which would normally seem ludicrously anti-social and feeling pretty good about ourselves.

And while we all want to get outside, outside can be crowded. Smart people are avoiding busy beaches and crowded trails. The District of North Vancouver has closed down the ultra-popular Quarry Rock and Lynn Valley Suspension Bridge trails. The big Vancouver-area resorts, Cypress Mountain, Grouse Mountain and Mount Seymour, are shut down, along with every zoo, water park, or other outdoor playplace.

1,872 words · General topics, Hiking and backpacking "policy"

This August I’m off hiking in Jasper and Banff National Parks. Take the train in to Jasper, camp for a night in the frontcountry, hike a trail, take the bus to Banff, another frontcountry night, more hiking, camp at Lake Louise, then head home. Since I am the sort of person who enjoys planning trips almost as much as going on them, I had this planned out, with routes researched, campgrounds picked, and schedules ready, before Christmas.

Good thing. I needed a night in a frontcountry campsite in Jasper; reservations opened up January 7. The largest campground in the park is under renovation for all of 2020 so I played it safe, got up early to snag my spot. This was smart. Parks Canada’s database server failed under the strain of us early-risers; as errors and “processing…” queues kept me waiting I could watch the sites I wanted turn from green to red. Luck was on my side: I got in. But that was merely the first battle in a long war, a campaign of all against all between thousands of fellow-travelers from Canada and around the world, for the right to go camping.

The worst part is, there isn’t a better way.

My Victoria Day long weekend was spent at Golden Ears Provincial Park near Maple Ridge, British Columbia. I’ll diarise about that another time; suffice to say it was a bust. There were clouds and bugs but most of all there was a crowd; a happy, rowdy pain-in-the-ass. At a spacious campground 45 minutes from the nearest parking lot people gave up and went home by three in the afternoon. The survivors seemed like nice people; the problem is that they were there. Enjoying the outdoors in their own way so, just by being around, we made that enjoyment a bit less for each other.

This was obviously going to happen. Golden Ears is a popular park, being gorgeous, easy to access and getting easier, and possessed by that enormous mass popularity of many local nature spots. Golden Ears, like Garibaldi and Alice Lake and oh God I’m going to stop listing them before I get depressed, is going to be too popular to be fun a lot of the time. The same applies for many day-hiking spots in the Vancouver area, and here I’m particularly thinking of the Lynn Canyon Suspension Bridge and the beautiful Quarry Rock viewpoint. The /r/Vancouver Reddit thread on Quarry Rock Victoria Day gave me all the bad feelings. And, going not that much further afield, the world-famous West Coast Trail is renowned as a hotspot for all the bad things the phrase “world-famous” implies in hiking culture.

Of course, backpacking in Golden Ears is an immensely popular overnight experience, so there is a cost attached. That cost is, um, $5 a night. Paid, by the way, essentially on the honour system.

About the Author

Ben Massey. Backpacking enthusiast, creator of this site, former writer of sports articles for several websites and one magazine, all-round handsome guy, and writer of his own blurbs.

Unless otherwise noted, all content copyright 2016—2024 Benjamin Massey. All rights reserved. Any icons or trademarks used are the sole property of their respective companies. Powered by Wordpress.