I like food (response from anyone who’s met me: we know), and backpacking cuisine is a frequent topic. From the cruise ship passengers who gawk in awe when I say I’m going off-grid for three nights and ask “what do you eat?“, to big-time through-hikers who get really good at assembling weeks worth of reasonably nutritious meals at gas stations, everyone’s got questions and some people have answers. It’s a very personal topic. Most beginning backpackers pack their fears, and in no case more than food: there is a fairly irrational terror of going hungry in the woods, when really all of us are fine if we hike and fast for a day. The authorities always recommend that we pack at least a day’s worth of extra food when we’re in the woods, and even allowing for that, it’s very easy to overestimate how much we actually need.

Today we can go to any outdoor store and buy lovely prepackaged meals of dehydrated deliciousness, which most backpackers do. However, those meals are expensive and their convenience comes at a cost beyond money. I’ve taken to making my own meals at home and packing them along. When I mention this in conversation, the next logical question is “oh, you got a dehydrator?” and the answer there is no: dehydrators are expensive single-use appliances, but there are loads of good dehydrated ingredients on the market today which anybody can use to assemble meals that are cheap, nutritious, filling, and yummy.

When packing food, and everything else, you make tradeoffs. However, after all these years, I’ve hit a system that works for me. I do not hike as hard and fast as a real through-hiker, but I do pretty well and am used to packing and hiking for two weeks between resupplies.

When backpacking, I eat two real meals every day: breakfast before I leave camp in the morning, dinner when I get to camp in the evening. A “real” meal is one where I get out the pot and the spork, and usually the stove. Some people like hot lunches but I’ve never felt one necessary. Digging into the backpack and busting out all my kit in the middle of a hike is a pain in the rear that I’d go to quite a bit of trouble to avoid. For mid-day nutrition I have two snack bars tucked into my hip belt, which I nibble on a break whenever I feel lunch should be. It doesn’t sound like much, but it’s all I need when I’ve got the two real meals in me, and has the advantage that on a really miserable day, I can hide in the tent and skip a hot meal without starving. Fairly often I come back from even long trips with a lunch or two left over, from days when I got to camp fairly early and didn’t really feel like I needed it.

When I got started backpacking I did what most people do and bring the big dehydrated meals from Mountain House, Alpinaire, and the other companies you might be familiar with. These have several advantages:

-

They’re easy. Grab package, go. Pour boiling water into package. Stir. Wait some period of time, like ten to fifteen minutes. Eat. Shove empty bag into trash bag. The cooking pot never does anything other than boil water so it stays clean, and you’ll probably lick the spork pretty spotless.

-

They’re trustworthy. Many of these are aimed at the survivalist market and, left unopened, have multi-year shelf lives. Their ingredients are inherently stable and they’re well-packaged. You don’t need to worry about them going off in transport or deteriorating if you’re hiking in the sun for ten days before you eat them.

-

They reduce planning to triviality. However many dinners and breakfasts you need, go buy that many from the local outdoor store before you get out. If you hike a lot, why not buy a case of something you like online? There’s nothing to think about harder than counting.

-

The calories-to-weight ratio of a prepackaged dehydrated meal is hard to beat. My favourite prepackaged dehydrated meal is slightly more energy-dense, calories per ounce, than my favourite made-at-home meal.

-

Many of them are very tasty.

There’s a reason experienced and competent hikers stick with these types of meals. However, over the years, I have found that their disadvantages are decisive.

-

Most significantly, they are expensive. If you go to the Mountain Equipment Company today, you’ll find that a dinner starts at around $13, with the good ones at $15, and breakfast is never less than $10. Not less than $23 a day, plus whatever you do for lunch. Not outrageous, but not trivial.

-

A pair of such meals over the course of a day is usually not really enough. When I hiked with them I found that I always wanted something else over the course of a day. When I did the Juan de Fuca Trail, in 2017, I had two dehydrated meals a day plus bars for lunch and got quite hungry, so in the future I’d pack along something like a Mr. Noodles that added bulk both to my belly and my pack. Packing my own meals, on the other hand, I am always hungry before dinner but never walk off the trail feeling like I’m starving.

-

They’re bulky. Those packages, meant for long-term storage, survival, and cooking in, tend to be around six inches by six inches in area. They don’t fold up that well. Over the course of a long trip, they take up more space than you think, and then of course you get to pack the trash out, replete with stray bits of sauce in odd corners of the foil to attract the critters.

-

They offer less room for customization. When hiking, I am always glad for more protein, so I have an ounce of vanilla protein powder in my cereal instead of (or as well as) some powdered milk. I like fruit, so I throw some dehydrated berries into my cappuccino oatmeal. I like whole milk, not skim; I like fresh cheese, not powdered, and I can have all these things when I pack my own food.

-

Finally, when buying food off the shelf, you are at the mercies of supply chains and the other hikers who got to the shelf before you. Many a trip of mine has been made slightly worse because the local stores were out of the meals I like and I was stuck eating borscht or something1. If you stock your ingredients and make your meals at home, not only do you save money, but you get what you want, at least until the supply chains really turn nasty and the stores are out of cheese.

When I make my own backpacking meals, I get most recipes from Andrew Skurka. Skurka is an accomplished through-hiker turned guide who is used to making meals in massive bulk for varied, but experienced, parties of clients on trips that last between three and eleven days. His recipes, which I do not reproduce here as they are his intellectual property, are designed for his needs: they have to be affordable, quick, light, nutritious enough for hard days (harder than those most backpackers seek out), and stable enough to be assembled months in advance, shipped to Alaska, put on a bush plane, shoved into a backpack, and carried for a week and a half without getting anybody sick enough to sue Andrew Skurka Adventures LLC into the ground. Best of all, he then surveys his clients on which meals were good and which ones weren’t, meaning the research really is done for all of us.

This lines up nicely with a backpacker’s requirements. I also have a few of my own favourite recipes, particularly for breakfast which is sort of easy, but where I’d be without beans and rice or mushroom bacon ris-oat-to I don’t care to think.

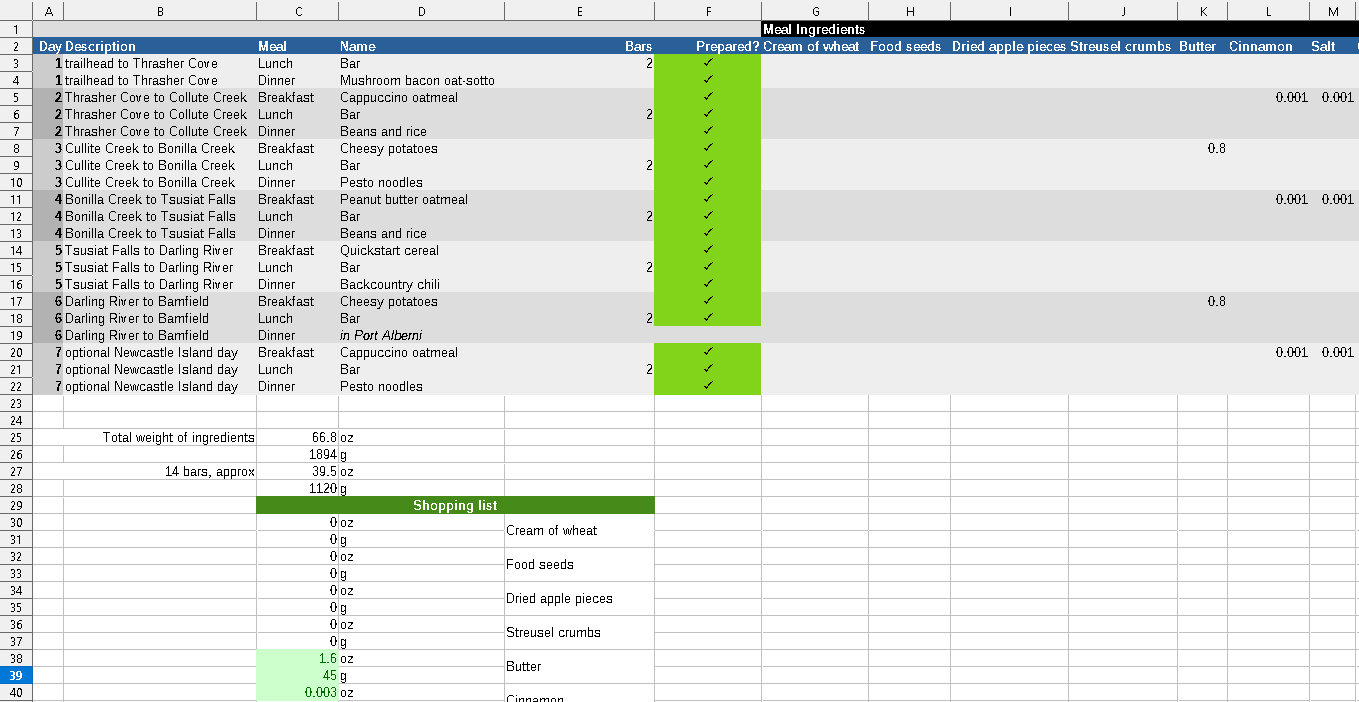

My system is simple. I have a spreadsheet with the recipes and their ingredients laid out for me, and for each trip I create a new tab listing out the days of hiking and the meals I plan to have, giving me a quick-and-dirty grocery list, a calculation of the weight, and letting me pack and plan. Of course I don’t actually eat the meals on a fixed schedule, I have what I’m in the mood for when I’m in the mood for it, but planning this way lets me make sure I don’t miss a day and recalls the requirements of the trip to mind: “this day will be a fifteen-miler over a mountain pass, I should probably have something pretty filling for that morning.” This consciousness of what you’ll be doing and eating is a further, slight advantage to packing your own meals.

A household food scale and a bowl is all you need for prep; who cares about nailing the quantities to the tenth of an ounce? Dry ingredients go into sandwich-sized freezer bags, one per meal. Most of Skurka’s recipes have something which should be added at cooking time: corn chips, grocery-store parmesan cheese straight out of the Kraft shaker, real cheese, olive oil, butter. These ingredients are put into their own resealable bags; freezer bags work but I like the sturdy and reusable Stasher bags for these cases. Butters, peanut or otherwise, go into the classic Nalgene jars, and for liquids such as olive oil I like the Humangear GoToob squeeze bottles, though be warned that if you’re packing at low elevation and moving to altitude, the contents will expand in transit, so I wrap them in a cheap sandwich bag to control leaks.

On the outside of each bag I write the recipe and the fraction of what I need to add when cooking in permanent marker. For example, if I bring three meals requiring fresh cheese, I write “⅓ cheese” on the outside of each bag that uses it. Much easier than trying to weigh out quantities on-site, no thinking in camp required. Snack bars are just snack bars, they’re easy to pack; I like Hornby Organic and GORP bars, both made in Canada, though for the sake of variety I tend to add fruitier bars off the grocery store shelf from the big brands for long trips.

By this means I get a lot of food, in a way that’s very conveniently-accessible when I need it, into a tiny amount of space. For my 14-day 2022 trek, my food filled one Ursack XL and one standard Ursack. When I finished that hike, I was not particularly hungry, though out of tradition I still demolished an entire pizza by myself in Jasper along with fifteen beers.

They are delicious, they are filling, they are cheap. Comparing and contrasting the costs of a breakfast and a dinner makes the advantage clear (all prices in Canadian dollars, and except where linked are online-grocery-store non-sale prices for normal-sized packages: if you really did this you’d get better rates). It’s definitely possible to use reusable bags or containers for these, but if you’re not, add twenty-five cents a throw for a good, name-brand freezer bag in the big box:

| Breakfast | |||||

| Cheesy potatoes | Alpinaire Strawberry Granola |

||||

| Instant mashed potato | 1.3oz | $0.88 | One packet | 6.5oz | $11.95 |

| Nutritional yeast | 0.1oz | $0.22 | |||

| Dried onion | 0.05oz | $0.53 | |||

| Cooked bacon | 1.0oz | $1.80 | |||

| Cheddar cheese | 1.0oz | $0.60 | |||

| Salted butter | 1.0oz | $0.41 | |||

| 537 calories | 780 calories | ||||

| 4.5oz (119 cal/oz) | 6.5oz (120 cal/oz) | ||||

| $4.44 (120 cal/$) | $11.95 (65 cal/$) | ||||

| Dinner | |||||

| Beans and rice | Mountain House Lasagna with Meat Sauce |

||||

| Dehydrated refried beans | 2.0oz | $2.20 | One packet | 3.6oz | $15.95 |

| Instant rice | 1.5oz | $0.45 | |||

| Cheddar cheese | 1.0oz | $0.60 | |||

| Corn chips | 1.0oz | $0.60 | |||

| Taco seasoning | 0.2oz | $0.47 | |||

| 668 calories | 440 calories | ||||

| 5.7oz (117 cal/oz) | 3.6oz (122 cal/oz) | ||||

| $4.32 (155 cal/$) | $15.95 (28 cal/$) | ||||

All four meals are stomach-pluggers, the sort of thing I want in me for good hard hiking. The caloric density of the made-at-home meals and the storebought meals are very close; actually, slight advantage to the storebought. But the price comparison is overwhelmingly in favour of doing it yourself, even factoring in the cost of your time (these really do not take long to put together at home for a big trip). Moreover, and this is very personal, but the Andrew Skurka meals feel more filling than their calorie counts: the trail food makers are good about protein but tend to neglect fat. Mountain House boasts that their lasagna has 22 grams of protein, which is a lot on the trail: beans and rice has something like 27, and more fat. Carbs are easy, a snack bar is all carbs, but proteins and fats are what you really want when you’re cooking.

The case for making your own meals is therefore, objectively, very strong. However, there are some disadvantages.

-

Bringing non-dehydrated ingredients into the outdoors. These recipes will often call for something like cheese, or bacon, or butter, or some other ingredient that you know will spoil if you don’t refrigerate it for weeks at a time. If you’re hiking in the mountains the cool nights will help but it’s still not a fridge. To some degree, you can mitigate these risks with good packing: storing cheese in fairly opaque, reliably-resealable containers, for example. However, our generation has become more fastidious about food safety than our ancestors, and you do need to push through that mindset. When I packed hard cheese for two weeks in 2022, it developed moldy bits. I shaved them off and ate the rest. Many of my meals have bacon in them, which I fry up at home, pack, store in the fridge, and eat without worrying about it. I’ve never had a real problem. I did, once, have one instance of intestinal distress, but it didn’t recur and could have been anything. You have that sometimes with prepackaged meals too, to say nothing of at home. Salted butter keeps pretty well in a sealed container, mass-market peanut butter is so full of preservatives that it’ll go bad way after you do, but you sort of need to trust. This is a hard habit for some of us to get into.

-

Cooking in the pot means your pot has food in it, which means it has to be cleaned. How cleanliness-focused are you out there? I make a fairly watery meal which leaves little residue, and I chase most of it down into my stomach with a potful of cold water. Living like this, my pot is always sufficiently clean that I don’t have to make a special cleaning trip, and I never taste the previous meal in the next one. This is good enough for me.

-

The ingredients can be harder to obtain. In Canada, Good2GoCo sells wonderful #10 cans full of dehydrated ingredients that keep in the cupboard for years. Other esoteric ingredients can be found on Amazon, or in your local bulk section, but you need to shop around a little. However, this is offset by the fact that, once you find a source, you’ve got many, many trips worth of food on hand. It took me more than two years of steady hiking to finish off one can of dehydrated refried beans. Most of the ingredients are probably things you will have at home anyway.

-

Hey, it is work. Time is a cost. You have to prepare and bag all these meals yourself at home. I usually get my meals ready over the two weeks before I go in moments I’d otherwise spend on YouTube or writing an unremunerative blog, and keep them in the fridge. In the field, there is no time difference. “Just add water” sounds quicker than “add to water, then add cheese and corn chips,” but when you’re actually using those pre-made packages there’s a lot of stirring the weird hard bits out of the corners and cutting the top of the bag off so your spork can get the food out; nothing significant, but neither is tossing two more things into a pot.

That is what I do. Neither pre-made meals nor meals made at home are wrong, and if you’re well-off and never going for more than a week once a year, the storebought ones might make more sense. Here are some things I have seen people do that I for one do not bother with.

-

Electrolytes. People say that hiking is a marathon, not a sprint, but that’s a metaphor: it really isn’t a marathon either. Sure, you sweat a lot when you’re hiking on a hot day, but nothing compared to a big run, and the best answer is “go slower, dunk your hat in the stream, and do what it takes to sweat less.” Electrolytes are great when you can’t stop, won’t stop, can’t even slow down, and your shirt is sticky-wet with perspiration: these are not normal hiking conditions. Rather than mess around with gels and capsules, I replace salt at meals. Never had a problem.

-

Vitamins and supplements. Another silly thing to mess around with. Yes, all backpacking meals are necessarily short on fresh greens, but you have to go more than a month without any vitamins, working hard, to worry about dietary deficiency. You won’t get scurvy. The only way you’ll get beri beri is if you’re drinking yourself into unconsciousness every night. Vitamin capsules are usually just an expensive way to pee vitamins out anyway. They’re a faff, they’re weight, they’re messing about with your body chemistry. If you’re hiking for four months, eat an orange on your town days. If not, don’t worry.

-

Drinks other than water, caffeine, and booze. Fresh stream water tastes mighty grateful on the trail. I’m not sure why you’d ever flavour it. “Oh, I don’t like fresh water.” Are you sure? Do you really not? Have you really tried skipping dumping the Kool-Aid pack into your bottle? Hey, if you like it, go for it, hike your own hike, but buying a fancy scientifically-formulated drink mix is another waste of cash, weight, and time. Tea or coffee, and the flask full of liquid relaxation, are acknowledged comfort items rather than dietary requirements, so don’t really fit into the category of this post, though I’ve noticed that while I caffeinate every morning at home, I’m having tea on fewer and fewer mornings in the backcountry…

-

Snacks. Good ol’ raisins and peanuts! Delicious! Who would argue? If the food’s there you’ll eat it, but there are advantages to sticking to a fixed ration. I am really fat, and I carry a heavy bag, and two meals and two bars is honestly all I need for weeks at a time. I don’t want to tempt myself into carrying more food than I actually need. That only makes hiking and packing harder, all for the sake of grazing through the snack bag for calories that, when push comes to shove, I don’t actually need to haul on my back. People doing routine 25-mile days are an exception here: there’s a point of exertion where you really need all the calories you can get, but more backpackers think they fall into that category than actually do. Also, if you’re backpacking with kids, you need to keep them happy, so in that case bring all you have to, but otherwise…

-

“Civilian” off-the-shelf ready-to-eat meals. You can make good backcountry meals with pasta, or stovetop stuffing, or instant soups, of course you can, but they’re short on caloric value and tend to be very carb-heavy. Grabbing grocery store boxes of just-add-water is a good way to go hungry and is penny-wise, pound-foolish. Most ordinary convenience foods are, essentially, bulk, or appetizers meant to go with your chicken thighs, and while you don’t need to be obsessive about vitamins and minerals for an average backcountry trip eating Kraft Dinner and Mr. Noodles just won’t do: you need to watch your macros. Get some protein and fat in there, and at that point, what you have is a recipe.

More people should be making their own meals out there. Yeah, I don’t like paying Parks Canada $15 a night for a backcountry site they don’t maintain either, but if you’re bringing storebought meals you’re throwing more than that away. It’s not hard, it’s not expensive, you don’t need new appliances, you need an $18 box of freezer bags you probably already own anyway. Give it a shot. You might like it.