Sir Ranulph Fiennes is not everyone’s favourite adventurer, though he is mine. When the Guinness Book of Records calls you the World’s Greatest Explorer, people resent it. He has never feared positive publicity and has always been honest that he adventured to earn a living. Every year or two he releases a book, often hashed-together bits of his old ones. His attitude towards telling a straight story, as seen with his 1991 true-story-turned-fiction??? thriller The Feather Men, can be… negotiable.

There are things in common with Colin O’Brady, who now may be nobody’s favourite adventurer except his own. O’Brady holds records of the modern type, fastest to this, youngest to that, but won prominence in 2018 when, as the story goes, he became the first man to travel all the way across Antarctica, via the South Pole, by his own power, solo and unsupported. The specialist press was all over this claim even while it was being made, but after years of uncritical adoration from the mainstream media, Aaron Teasdale’s 2020 National Geographic article “The Problem with Colin O’Brady” put the fat in the fire.

Both Fiennes and O’Brady are professional adventurers, corporate speakers, and authors. Both were upper-crust before they were born; the “Sir” in “Sir Ranulph” has been with him all his life as his father, the second Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes baronet, was killed in action before Ranulph’s birth. O’Brady’s mother is a prominent businesswoman, NGO board member, and Democratic politician. Fiennes went to Eton, O’Brady went to Yale. Both are sometimes criticized for how forthright they can be about their true accomplishments.

Both men have skied the Antarctic landmass; Fiennes in 1992–93, with Dr. Mike Stroud, and O’Brady solo in 2018. Both wrote books about their expeditions, and neither quite achieved everything that their biggest fans might claim. Now the similarities stop. In one case, we see what might be called “honest spin,” a groping for lesser success rather than failure; not to be encouraged, maybe, but to be forgiven. In the other, we see spin of a different degree, better suited for politics than the white Antarctic.

Mind over Matter: The Epic Crossing of the Antarctic Continent1

Sir Ranulph Fiennes

London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1993

Hardcover, 326pp.

The Impossible First: From Fire to Ice—Crossing Antarctica Alone2

Colin O’BradyNew York: Scribner, 2020

Kindle edition, not long.

The trouble begins with the phrase: “unsupported crossing of Antarctica.” Nothing could sound more obvious, which is precisely its danger. Unsupported: just you or your party with your own resources, no snowmobile with a support crew that sets up the tent and makes the coffee, nobody laying supply caches, nobody getting dropped off or picked up, no stops at McDonald’s, if your ski breaks you have a spare or go without but you certainly don’t get a new one brought in. Crossing: you go from one end to the other end, and if you’re thinking ahead you’ll add “and you pass through the middle on the way, so no slicing off a peninsula!” Antarctica: big cold place south of everywhere.

The details are where you find cracks through which the unscrupulous drive. “Unsupported,” eh? If you hike down an established trail for two weeks, without resupplying or getting someone else to help you out, are you and your friends “unsupported?” Who made that trail? Who cuts out the deadfall (well, some of it), puts up the bridges, flags the uncertain bits? Even on trails that see a chainsaw once every two years, quite a lot of support went into making them however usable they are. You wouldn’t presume to compare yourself to those who bushwhacked through it before the trails were even a thought; you’d feel ashamed.

How about “crossing?” The geographical centre of Canada is near-as-makes-no-difference Yathkyed Lake, in Nunavut, south of Baker Lake and west of Hudson Bay. Suppose you flew to the western coast of Hudson Bay, traveled a few hundred kilometers to Yathkyed Lake, then blazed south through Manitoba to the American border. This would be a formidable backcountry adventure and you should get a book out of it. But you would never say that you crossed Canada, would you? What about, for example, the entire Canadian Arctic? You started from one end-point, went through the middle, and ended at another end-point, but you left out half the bloody latitude of the country! Some crossing!

Finally, “Antarctica.” Surely devoid of ambiguity, or at least any ambiguity an adventurer, who doesn’t give a toss about tectonic plates, can’t safely ignore. However, when one speaks of exploring Antarctica, the mind goes back to the early twentieth century. Scott. Amundsen. Shackleton. Mawson. Their era has a name: “The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.” It is part of our common heritage, Amundsen’s dogs versus Scott’s men, “I am just going outside and may be some time,” Shackleton bringing home the entire crew of the Endurance against all hope, Mawson surviving alone after both his companions died. All their expeditions were different, but all arrived by ship. When Scott, Amundsen, and Shackleton tried for the South Pole, they started not with a flight to the most coastal point of the landmass, but by spending weeks sledging over the Ross Ice Shelf. Four of Scott’s party of five got to the South Pole and back across the landmass just fine, but then they had to cross the ice shelf and perished. Shackleton’s Ross Sea support party for his attempted Antarctic crossing had to sledge across the ice shelf, and three men died. The ice shelves are in broad terms permanent, vast, and hostile. They are the very devil to pull sledges over, they have fearsome crevasses and terrifying blizzards, they impose enormous physical challenges, and they killed more heroic age explorers than the interior did. The men of the heroic age called the Ross Ice Shelf “the Great Ice Barrier.” They are not an afterthought. In the geological sense maybe Antarctica is the landmass, but when you’re talking about exploration, if you leave the ice shelves out, you’re leaving out most of the story.

In the 2020s a system, the Polar Expeditions Classification Scheme (universally referred to as PECS), has been established to close those gaps. Take a look at their guidelines if you want to learn how far such common nouns have been abused. We learn, for example, that:

A journey is Unsupported if:

- it does not receive any external resupply of food, fuel or equipment, either pre-placed or delivered during the journey

- it does not off-load anything but human waste and greywater

- it does not enter buildings, aircraft or vehicles, or tents other than their own, during the course of the journey, in particular base camp-style tent (except when instructed to do so as a condition of logistics support, such as at the South Pole)

- it does not use any type of road, vehicle track or marked route except when following routes into, out of or around bases, stations and camps as directed by authorities.

- it does not use a vehicle that provides physical and/or psychological support

- no team members are evacuated

A journey may only use the Unsupported descriptor if it has denied use of all types of above support for its entire journey.3

There is nothing about GPS, or satellite messaging, or weather forecasts, or even aerial reconnaissance; no early-twentieth-century manifesto for the imaginary purist. It is a simple attempt to group like with like. PECS is also not retroactive; indeed, PECS cannot be retroactive without losing meaning. It denies you “unsupported” status if you discard unwanted gear en route, which was common practice until about yesterday. PECS distinguishes between expeditions that use wind assistance and those that do not, but this the product of huge improvements in para-skiing; starting with Scott parties got some use from the wind when it favoured them, but twenty-first century kiting techniques allow adventurers to achieve incomparable feats across the ice. There was no single point where the switch flipped, but sails were one thing then and another now. A specialist may appreciate these distinctions but the mainstream media will hardly bother to differentiate between, say, the different meanings of the word “crossing” without some authoritative source.

In his 1993 book Mind over Matter: The Epic Crossing of the Antarctic Continent, Fiennes details his and Dr. Mike Stroud’s attempt to sledge, unsupported, from one end of Antarctica to the other. Fiennes had crossed Antarctica before, as part of the 1979–82 Transglobe Expedition, but by snowmobile and with support. This crossing was, in its conception, a crossing: from the edge of the Weddell Sea on Berkner Island4, over the Filchner Ice Shelf, through the South Pole, down the Beardmore Glacier, and finally to McMurdo Base on Ross Island at the far end of the Ross ice shelf, where like the heroic age explorers of old they were to be removed by ship.

Three cruise ships take tourists to MacMurdo base [sic] in mid-summer each year and one of these was due to depart from Antarctica at 6:30 a.m., and not a minute later than, on 16 February 1993. If we could reach the coast by then the ship’s operators, Seaquest, kindly agreed to remove us at no cost and take us to Australia (providing we took passports).5

Perhaps you saw, barely visible, in the very title of the book, a hint of trouble. The Epic Crossing of the Antarctic Continent. Fiennes and Stroud laboured for over three months, nearly 1,400 miles, with sledges that started the journey weighing 485 pounds each. They made it as far as the Ross ice shelf, and stopped, more than two hundred miles short of the sea.

Their chances of catching their ship were zero, and in fact they lacked the food to make McMurdo Base at all. Stroud was having hypothermic events and Fiennes was worried Stroud, a husband and father of two, would die in the traces; Stroud was himself worried about Fiennes. They were freezing and starving to death as the polar autumn came and their unspeakable, prolonged physical effort burned more calories than it is biomechanically possible for diet to replace. Stroud, a medical doctor and nutrition specialist, ran studies with himself and Fiennes as lab rats which demonstrated an average burn of 6,000 calories per day, reaching 8,500 to 10,000 calories during the most strenuous climbs. Not only had they no fat reserves to keep warm but despite exercising hard every day with the best possible diet, both men lost significant muscle due to sheer starvation. Stroud’s lower body strength at the end of the expedition was measured at 50% of when he started. They had to call it quits:

Whether or not London Insurers would pay for the ANI6 costs of retrieving us would depend on their definition of our state of health when found. Mike’s medical summary included, along with details of various wounds, a description of my feet as ‘toes infected and ulcerated due to frostbite with large areas of devitalized tissue’, and ‘eroding ulcer on right foot, present for seventy days but increasing in severity since supplies of appropriate antibiotics finished’.

He described his own debilitation: ‘Rapidly increasing vulnerability to cold demonstrated by an episode of hypothermia two days prior to pick up. Additionally, episodes of mild hypoglycaemia, due to starvation and high levels of exercise, are increasing in frequency and severity and posing the probability of a very dangerous situation.’

We will never know how much further we could have continued because there are too many ifs and buts. If, like Scott, we had no option but to battle on, it is my opinion that we would have died short of Ross Island.7

They were lucky. With their primitive satellite communicators out of action, they had to set up their radio antenna and call for help rather than press a big red button. Luckily they were able to get through, luckily the weather was clear for a plane to land, luckily both men survived and are, in fact, still with us. But they had failed in what they had set out to do.

What they had done was astonishing. Pushing 1,500 miles of manhaul without support. They had used a sail in the right winds, but this was so seldom, and to relatively inexpert paraskiers so risky, that accounting for the weight Fiennes considered the sailing equipment barely a net gain8. Most importantly, while they had not achieved the crossing they had set out for, the crossing Ernest Shackleton had set out for 80 years earlier, the crossing of Antarctica from water to water, they had crossed the landmass. So you see, in Ranulph Fiennes’s Wikipedia article today, that deceptively-simple sentence:

[In 1993 Fiennes] joined nutrition specialist Mike Stroud to become the first to cross the Antarctic continent unsupported; they took 93 days.9

Everywhere you look, Fiennes and Stroud were the first unsupported crossers of the Antarctic continent. By this point in the article you realize what an important qualification that is, but until you know it is an elusive distinction.

Fiennes knew. His narrative of the end of his expedition is not triumphant. He and Stroud badly wanted to make Ross Island and only its impossibility forced them to stop short. The quote above about insurance and death is typical of his thoughts. He triumphs the length of their journey, a record at the time by some distance, and proclaims that, by their great feats, he and Stroud partially exonerated Robert Falcon Scott’s much-reviled support of manhauling. He takes the undoubted victories full-heartedly; the lesser triumph of crossing the landmass comes more by side-long mention, earlier in the book, and is couched in justification for having to stop. Even the 2007 edition of his autobiography, Mad, Bad & Dangerous to Know, claims the crossing of the landmass in the same half-ashamed way, while trumpeting his and Stroud’s undoubted distance record.

We can be sure that, even after this, Fiennes thought the ice shelves were really part of a crossing because he proved it. In 1997, Norway’s Børge Ousland, the greatest polar adventurer of his generation, set out to cross Antarctica solo. Two other men attempted the same: Poland’s Marek Kaminski and England’s Sir Ranulph Fiennes. All three started, in slightly different spots, near the sea edge of Berkner Island, dropped off by air to cross the ice shelf. Because that’s how you cross Antarctica.

Ousland made it, all the way, across the continent and past the South Pole and the ice, 1,864 miles in 64 days alone, still the greatest journey of its type in history. Ousland’s success was enabled by his fantastic kiting skills, but the kites of 1997, though in Ousland’s hands a great advance on earlier models, were far short of those of 2010, and Ousland manhauled two-thirds of his mileage. For the kite to make a one-third difference, when Stroud and Fiennes had failed by 15% of their intended distance, was important, but also a tribute to Ousland’s guts and skill. He is the pioneer of long-distance kite travel in the Antarctic, and like all pioneers might easily have failed. Robert Falcon Scott tried to pioneer the snow machine and improve Shackleton’s success with ponies, and both decisions helped kill him. Ousland might have gone the same way. Fiennes relates a story where Kaminski, riding his kite, fell, concussed himself, and was dragged away from his gear before he came to; certain death, except that he was able to follow a trail of his own blood back to his sled10. Fiennes himself was evacuated only halfway to the pole with kidney stones, and Kaminski, well behind Ousland despite his own kite, arrived at the South Pole too late to even continue a crossing, let alone have any hope of beating the Norwegian.

That kite, though. To the historically-minded, it is to Ousland’s credit rather than his demerit, but to the adventurous it was an asterisk as large as Roger Maris’s. Scott and Amundsen hadn’t had kites like that. They’d had dogs, and nobody sets dog-driving records anymore except as historical re-enactment. Sir Vivian Fuchs crossed Antarctica in snow machines with air support in 1957–58, and I’m not sure anybody knows what the air-supported snow machine record for an Antarctic crossing is anymore because I’m not sure anyone cares. Adventure is imposing artificial hardship on yourself, and the greater the hardship the greater the honour. First someone does it at all, like Hillary and Norgay climbing Everest in a huge team with bottled oxygen, then someone does it the hard way, like Reinhold Messner soloing it without oxygen, and both enter the history books, get sponsorships and speaking gigs, and never have to work 9-to-5 again.

Today’s adventurer, seeking a similar life, is running out of options. For some there is the novelty record, first woman of color to reach the South Pole and so on, and the sponsorships, honours, media worship, and cash flow to them like honey, but if you have the misfortune to be a white male too old to be the youngest anything, and too young to be the oldest anything, that is out of bounds. Adventuring remains a very white male pursuit. So if you are as driven to make a name and a living as Sir Ranulph Fiennes, how about crossing Antarctica without snow machines, without air support, without a kite, without anything but your own two legs?

There’s just one problem: it might be impossible. It’s too far, too hard, too high, and too cold. Science can improve training, lighten gear, ease navigation, provide a safe rescue (some of the time), but nutrition science, in terms of getting the most calories into the least mass, has topped out, and food is so vastly your heaviest problem that lightening your tent by a pound is one flake in a blizzard11. You can’t safely skimp far on fuel, the second-heaviest item, in a frigid land with zero liquid water. Science cannot make the body absorb more calories in twenty-four hours nor make the summers longer and warmer. It cannot shorten the continent.

Or can it?

Fiennes and Stroud had gotten the laurels for an unsupported crossing of the Antarctic continent. Never mind that they’d fallen short of their intention; what they did got both men OBEs and plenty of opportunity for future expeditions12. It was a precedent, and if Ousland and even Fiennes had been too honourable to pursue it to its logical conclusion then that was a simple matter of changing the idea of honour, a moral burden as easy to discard and as obsolete as a theodolite13.

In 2009–10 the American Ryan Waters and the Norwegian Cecilie Skog re-did the spirit of the Fiennes-Stroud route, from the sea at Berkner Island to the beginning of the Ross Ice Shelf, in 70 days, improving on Fiennes and Stroud both on time and in not using the wind, allowing them to claim the “unsupported, unassisted” record. There is no suggestion, unlike Fiennes and Stroud, that they would have gone on to Ross Island if they could have, and the official victory photo shows Skog triumphantly in Waters’s arms with not even the vaguest hint of a job unfinished14. They wanted to one-up the Britons and did so, but now the end of the landmass was the goal rather than the consolation, and sure enough, all the headlines obligingly referred to the “first unassisted, unsupported crossing of Antarctica” without even the “Antarctic continent” semi-hedge.

Twenty years earlier Reinhold Messner and Arved Fuchs had “crossed Antarctica,” in the now-familiar partial sense, without animal or machine assistance but with a resupply at the South Pole. They had intended to march sea to sea but their logistics company was forced to set them near the land, right at the inner edge of the Ronne ice shelf. Messner, of “by fair means or not at all” fame, was reportedly so furious that the logistics company had to cut him a big cheque, but he and Fuchs were hardly going to go home from Antarctica just because they had the “wrong start.” Their expedition to the Ross Sea was a success, though marred by public bickering between Messner and Fuchs, and another precedent was set. What the agencies now call the “Messner start” is not even this already artificially-easy point but one another 70 miles east, presumably because Messner’s worldwide reputation for scorning modern shortcuts hides the fact that this is a colossal modern shortcut, reducing the length of an Antarctic expedition by about two weeks.

So if Messner and Fuchs could start on the shoreline, and Fiennes and Stroud could end on the shoreline… never mind that neither party had meant for that to happen. It could.

The first man to follow this logic to its conclusion is difficult to write about. After a much-honoured career in the British Army, 56-year-old Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Worsley, MBE launched his “Shackleton Solo” expedition in 2015. It was not Shackleton, solo. Shackleton, when he tried to cross the Antarctic, would have had to cross two ice shelves in full. Three men in his Ross Sea supporting party, the Rev. Arnold Spencer-Smith, Aeneas Mackintosh, and Victor Hayward, died on the Ross Ice Shelf or the adjacent sea ice while moving supplies Shackleton would have needed had he made it that far. The ice shelves were very, very important to Shackleton. Worsley effectively skipped them. He started at the south, inland end of Berkner Island, saving over a hundred miles of ice shelf, though he had to cross a bit of it to climb to the Antarctic plateau. From there, he passed through the South Pole, unsupported and without sail, making his way towards the Shackleton Glacier, where he would ski just far enough into the Ross ice shelf for an airplane to pick him up. For anyone who read beyond the press releases and the deceptive title of the expedition, the truth was plainly stated, and a map and description of his planned route was right there15. You would have needed an appreciation of the history to realize what it was he was not doing.

Worsley would have made it. He was two or three days from success, with time and supplies in hand, but he fell ill. An aircraft was able to evacuate him to Chile, and his wife was rushed to his side, but Lieutenant-Colonel Worsley died of bacterial peritonitis January 24, 2016, leaving behind his wife and two children.

In the news coverage that followed the press naturally read “Shackleton Solo” to refer to an emulation of Shackleton’s attempted journey, heard that Worsley had been stopped 30 miles short of his finish, and went from there. The Guardian, bastions of precision, published an article on Worsley’s death with the usual lack of clarity and a map of which the most charitable comment would be that they successfully identified Antarctica. Worsley of course bore no responsibility for journalistic malpractice after he died, and it would be ridiculous to say that a man who made a widow of his wife trying to ski 900 miles should have gone for 1,600, but to get sponsorship, you have to get attention. The 1% of people who dove into Worsley’s journey could see the plain truth, but for the 99% who stop at the words “Shackleton Solo” and the inaccurate media coverage, it all sounded very different than what it was.

We come at last to Colin O’Brady, whose 2020 expedition account, The Impossible First: From Fire to Ice—Crossing Antarctica Alone (yes, really, sub-subtitle and all), it is impossible to recommend less. You can get an idea of it, and it is inadvisable to get more, by reading O’Brady’s official website on the expedition. O’Brady does write better than this—it would be bloody difficult not to—but the tone is authentic:

The History

Harkening back to the turn of the 20th century, humans have been trying to cross the continent of Antartica [sic]. Everest had been conquered, oceans has [sic] been sailed, rowed and even paddle boarded across solo 0- [sic] however, from the time Shackleton first set foot in Antartica [sic] over 200 years ago [sic!!!!!], a solo, unsupported and human powered crossing of Antartica [sic] still remained unfinished, leaving it one of the last remaining iconic “firsts” in modern exploration.

A Perilous Journey

In recent years, after the tragic passing of Henry Worsley and the attempt of Ben Saunders – two of the world’s most accomplished polar explorers – many have said a crossing of Antartica [sic] is IMPOSSIBLE [sic] Worsely [sic] and Saunders individually attempted via the historic Berknet [sic] Island starting point in reverence to Shackleton’s footsteps [sic].16

The word “Antarctica” is misspelled eleven times on the page17.

O’Brady, and his rival in the field former British Army Captain Louis Rudd, sledged from the “Messner Start,” involving even less ice shelf travel than Worsley undertook, to the very beginnings of the Ross ice shelf. The distance, 932 miles, was only 19 miles more than Worsley achieved, which should immediately call into question how impossible it could have been. It was less than two-thirds of what Fiennes and Stroud managed in 1994, admittedly as a duo (which makes no difference to travel speed and saves less weight than 24 years of gear evolution did) and with questionably-effective wind aid. Ousland, we are told, doesn’t count because he used the wind, but when the wind didn’t serve he manhauled more than Rudd and O’Brady did. To call it “impossible” would require either deceit or rank idiocy, though fortunately for O’Brady Wired magazine gave him the latter, as O’Brady’s site quotes: “it’s straight-up impossible to take enough calories with you to get across the continent of Antartica [sic, and might I add for crying out loud].”18

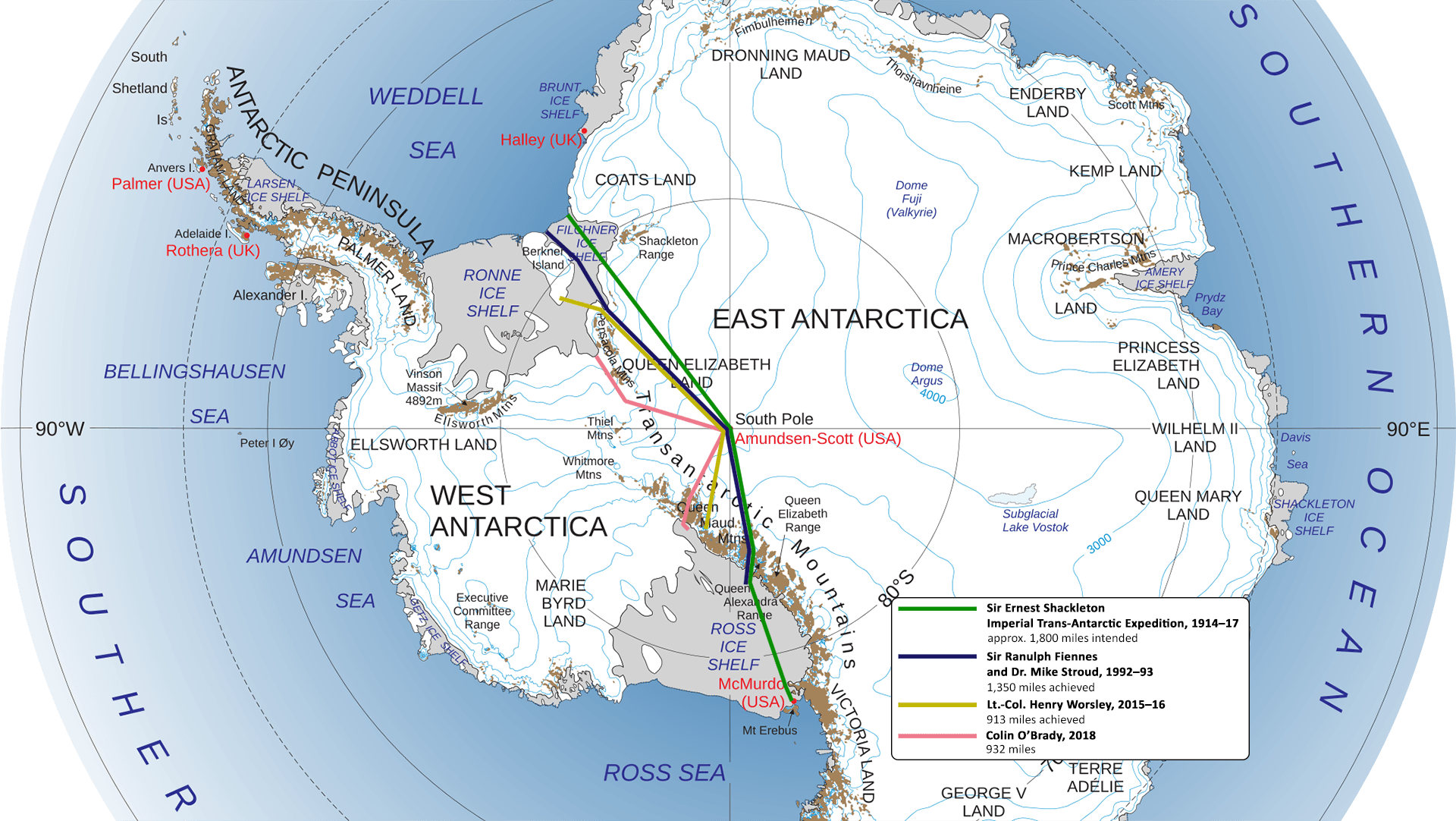

For the convenience of colour-blind viewers, the routes are, in order from the top near Berkner Island: Shackleton, Fiennes-Stroud, Worsley, O’Brady.

Click for a larger map.

Viewed on a map, even Shackleton’s plan to cross the continent leaves quite a bit out but O’Brady and Rudd’s “crossing” looks goofy. From the “Messner start,” one sweeps inland to the South Pole, then turns sharply to head back to the coast by the shortest possible route. The latitude of O’Brady’s “Messner start” was 82.79 south, and his official endpoint 85.45 degrees south19, meaning O’Brady crossed 11.7 degrees of latitude. For comparison, the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba are eleven degrees of latitude from their southern to their northern border. This “crossing of a continent” involved 40-odd more north-south miles than the crossing of a province; Fiennes and Stroud’s first camp, by comparison, was at 79.32 degrees south20 while their goal at McMurdo Base was 77.84 degrees south21, a goal of 22.84 degrees latitude not counting the .08 or so of a degree they made on the first day. The map on the New York Times’ slavishly-uncritical coverage of O’Brady’s race shows a big greater-than sign in the ice.

So it’s not much of a crossing; it is still sledging 930 miles, pulling hundreds of pounds, in a frozen, substantially uninhabited environment where something as treatable as peritonitis can kill, where you will not see another person for more than a month at a time. There have been genuine Antarctic frauds, people claiming they did something they never got near doing, but O’Brady’s feats, qualified though they are, are authentic beyond doubt. The author of this article could not come close to doing that and neither could almost any of his readers. So what if it’s not much of a record? We are not, actually, only interested in records. Jon Krakauer has made a career writing about expeditions that weren’t records. Adam Shoalts, a Canadian adventure writer of today, has gotten several best-selling books out of trips that weren’t records, but that were exciting, filled with natural history, and told in an inimitable style. Record-chasing is one pursuit, but not the only one.

Colin O’Brady does not seem capable of writing that type of story. Or perhaps he didn’t want to try.

What could happen next played out before my eyes like a waking nightmare: I lose my grip. The tent rises, I leap desperately for it but can’t catch it, and I stumble and fall. The tent disappears almost immediately into the white. I get up and run for it into the storm… and then… and then… I am lost. The tent is gone. I turn back and see nothing but the full whiteout of the storm. I have nothing to guide me back to the sled and no hope of surviving the night.

That horrible vision kept playing out as I held on desperately

I had no backup tent. No rescue party could ever make it through a storm like this, with zero visibility and rugged, uneven terrain that would prevent a plane from landing. I’d grow sleepy, then increasingly irrational, and finally I’d lie down, thinking that the ice was a nice place to rest. I’d die alone, in the cold, my body temperature falling.

It wasn’t the fear of death that really got to me—it was the realization that I’d never make it home. I’d never get back to Portland, never walk along the Willamette River holding hands with my wife, Jenna, never laugh around another campfire at the Oregon Coast with my parents and the rest of my family, never again smell the deep, peaceful aroma of a damp, bark-lined forest trail in the Cascade Mountains.22

Stripped of melodrama, O’Brady’s tent almost blew away before he had it staked out. Granted this is Antarctica, and he would have been in more trouble than most: his experience is familiar to the ordinary frontcountry camper, and his danger hinges on imagining “but what if I’m incredibly stupid?” He kept control of his tent by the way, though you wait almost to the end of the book to learn it formally.

But that’s page one. He wants to grab bookstore browsers with excitement. Perhaps it’s not a good sign this is the most exciting thing he can think of in 900-odd miles of sledging but does he get better?

No.

His expedition begins flying to the ice in the company of Louis Rudd, which makes sense since they’re both attempting the same “impossible” “crossing.” Rudd talks to O’Brady about his previous experience in the Antarctic and they swap opinions on gear. He allows O’Brady to take pictures of him, he shows O’Brady a picture of what Rudd looked like at the end of his earlier South Pole expedition, and allows O’Brady to take a picture of that. All the time, O’Brady approaches this conversation in the spirit of a master psychological warrior, convinced the older, more experienced Rudd is psyching him out, trying to get under his skin, and determined to win the Battle of the Airplane.

On a flight to sledge through Antarctica, there seems to be no more natural topic than sledging through Antarctica. With a former British Army captain and an American former triathlete it’s the main thing they have in common. When O’Brady chats to somebody hiking the same route as him in Oregon, does he think they’re having a mental duel? Every two-night backpacker in the world has had that talk! Ah, but O’Brady has to build it up, his opponent is not merely a hostile continent but the wily Captain Rudd. Cue the cut-rate psychobabble23.

Through the book O’Brady is the hero against the unfeeling hostility of nature as well as the cunning snares of his adversary, and of course there’s never any hint of thought that O’Brady might have been in his own head, that he was nervous and jumping at shadows, because that mars a plot that must lead to total triumph. The Rudd drama fills much of the book. Rudd, unlike O’Brady, initially does not publicize the GPS track, leaving it hidden behind a password on his tracker’s webpage. This is a most ordinary thing to do, I do it myself, it is a consumer-grade feature and not a nefarious plot. When O’Brady’s mother, back home in Oregon, manages to crack the password to view Rudd’s track, it is treated as a cunning piece of computer wizardry and a turning point in a mental war rather than a possible felony24. The New York Times, publicizing the race, asks for Rudd’s tracking info and he gives it without demur, but never mind: a few days later Rudd misses a tracking point or two because for whatever reason he wasn’t able to transmit, and this is again another great psychological gambit by the chessmaster Rudd, teetering on the verge of checkmate by O’Brady. The New York Times record shows Rudd did not miss updates for long; after stormy weather his batteries may have been short, and O’Brady treats Rudd’s claim of continuing blizzards as obvious deception. The Antarctic literature shows that hyperlocal weather patterns are not uncommon around the Ross Sea25 but anyway, O’Brady’s book needs Rudd as a foil and has little use for him as an adventurer.

It would not be fair to O’Brady to make it seem like his book is entirely about overcoming the scheming Captain Rudd, though that is a major note. He does spare time, occasionally, to talk about his trip.

On their respective first days, both O’Brady and Fiennes had trouble moving their fully-laden sledges. For Fiennes the story is told in the clearest fashion. He and Stroud had considered their irreducible minimum to weigh 485 pounds, and compares this to previous polar expeditions. 150 pounds maximum each for Amundsen’s dogs, 175 pounds each for Scott, Shackleton and Wilson on the Discovery; 253 pounds per man for Wilson, Bowers, and Apsley Cherry-Garrard on their 1911 “worst journey in the world,” with Fiennes quoting Cherry-Garrard’s book on how back-breaking it was. 200 pounds each for Scott’s men heading to the south pole. 353 pounds each for Roger Mear, Robert Swan, and Gareth Wood on their unsupported attempt on the South Pole. Reinhold Messner, who Fiennes reminds us is “revered internationally as the greatest mountaineer in history,” wrote of his own experience: “two hundred and sixty-four pounds is a load for a horse not a human being.”26

Then Fiennes and Stroud try to move their own sledges:

There was no excuse for delay; nothing to be gained by considering any further the unpalatable facts. Goethe wrote ‘Whatever you can do or dream you can . . . begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it.’ A spot of magic would be more than welcome.

We adjusted the manhaul harnesses about our stomachs and shoulders. I leant against the traces with my full 210-pound bodyweight. The near half-ton sledge paid no attention.

I looked back and spotted an eight-inch ice rut across the front of the runners. I tugged again with my left shoulder only, and the sledge, avoiding the rut, moved forward. I will never forget that instant. Never. I could pull the sledge. The fear that the full load would prove immovable had been growing into an ogre. That was now dispelled.27

You see how much is crammed into a story that runs three pages of text, and now little of it is about Fiennes and Stroud. Diving through history, never failing to acknowledge his predecessors, Fiennes establishes what 485 pounds actually means. By the time Fiennes is leaning against the traces and the sledge is not moving we know that he is not just spitting hot air; that his loads don’t just sound big but, objectively, are. And when Fiennes notices the rut, and gets moving, his triumph feels earned.

O’Brady’s load was also enormous but his only point of comparison is Captain Rudd. As part of his psychological war O’Brady declines to have his sledge weighed but knows it’s heavier than Rudd’s 286 pounds, calculating it at 375. Is that a lot? None of us have sledged an ounce over Antarctic ice before, we have no basis for personal comparison. Having read Fiennes you know they pulled more than Scott, more than Messner, more than Cherry-Garrard, a killer load. Without Fiennes’s context, O’Brady’s troubles sound like spin, throwing big numbers around to dazzle the audience. Even when he’s impressive he acts like a phony.

Which isn’t to say O’Brady does not bullshit. He, too, writes about the effort of trying to pull that great big sledge. Chapter Two, titled Frozen Tears, subtitled “Day 1,” begins its narrative with O’Brady watching the 1992 Summer Olympics. It swings back to talking to Rudd on the plane over, then a reminiscence of his dad telling him the most important thing to do before a swim meet: have fun. He lands on the ice and looks at it. There is a lengthy digression about how, when he was in first grade, he was hyperactive so his teacher sent him to run outside and when he came back in he was calm. It doesn’t sound like much of a story, and isn’t, but to O’Brady:

I’d need it all if I was going to make it across the ice. I’d have to reach back and find the boy who needed to run, and also the boy who found he could focus and solve problems when the energy was burned off. I’d need to remember my failures and my victories because of what they’d taught me. Rather than needing to burn off excess energy, now I’d need every scrap of emotional and mental fuel I could pull together. I’d have to open the door to my own past to have any hope at all.28

I’m sorry but what on Earth is this supposed to be? Back in the literary present, O’Brady walks to his sledge. He remembers the story of borrowing his wristwatch from a friend. He takes some selfie video for his social media. He writes down what he said into the selfie video for his social media, lest the future historian not be able to open MP4s and need a transcription of his fucking Snapchats. He tries to close his sledge up and breaks a buckle. Finally, something has happened cries the reader, falling like a starving man finding a steak upon O’Brady’s psychological assessment that if a buckle breaks that means he now lives in a new reality where sometimes things break and you need to fix them. A paragraph explains that, when you’re pulling heavy loads on ski, you are not using technical ski technique at all but rather the skis are “glorified snowshoes;” good insider detail of the sort this book could use 150 times more of. At last, some 12 pages into the chapter of the book subtitled “Day 1,” O’Brady tries to pull his sled.

Yet even with the traction of my [ski] skins, with those first steps it was immediately, horrifyingly clear that I could barely budge the sled at all. A stupid little buckle was the least of my problems. My sled felt anchored and unmovable on the ice. I managed to inch it forward a few yards, but then had to stop, go back, and check it out. Maybe there was something wrong with the harness or the runners. But there was no easy answer.

Whatever we’d done in removing weight, in Chile and again at Union Glacier, and whatever I’d done in training back in Portland, pulling heavy loads up grassy slopes at local parks, enduring endless minutes of planks with my fists in ice buckets, hadn’t been enough. My crossing of the Greenland Ice Sheet as a training exercise—four hundred miles in seven days—hadn’t been enough either.

I leaned in and managed a few more steps forward before I had to stop to catch my breath. I had more than nine hundred miles to go, and getting even twenty feet from where the plane had dumped me was already painful.

I became, with every next step, aware of my body—the harness yanking deep into my shoulders, my lower back arching forward to help my legs, which should not, I knew, hurt this much this soon. Something was very wrong and I couldn’t help but cry, mostly because, pitifully, I was feeling sorry for myself. I quickly learned how Antarctica dealt with such pity; the tears immediately froze to my face. More ice in a world of ice, and now I was even making it myself.29

It is a mystery how anyone deals with paragraphs like these without screaming obscenities. There’s no rule which says O’Brady, the Oregon rich kid, has to be as phlegmatic as Fiennes, the army veteran who’s done at all and been shot at by Arab Marxists. O’Brady is entitled to cry, and entitled to write about it when he does, but after the fact some self-awareness, some perspective, is what makes it a story. Fiennes and O’Brady both pulled brutal weights, Fiennes demonstrates what that really meant and wins points for overcoming it; O’Brady’s actual physical achievement is hardly less but all he gives us is ME ME ME ME ME ME ME ME ME until the reader wants him to fall into a crevasse. As with his self-declared psychological war against Captain Rudd, there is no satisfying ending, no realization with a laugh that he’d lost his head. This is the true O’Brady, self-absorbed and with an eye on the corporate lecture circuit, and the entire point of exposing vulnerability like this is so at the end he can (spoiler alert) pat the sled like an old friend, having overcome and self-improved, and hopefully get out of the hotel conference room in time to cash the cheque before the bank closes.

The narrative hardly advances without plunges into autobiographical dreck. If you want to learn what it’s like to sledge hundreds of miles in Antarctica, The Impossible First: From Fire to Ice—Crossing Antarctica Alone is not the book for you. If you want to sit an undergraduate exam on the greatness of Colin O’Brady, you’ll be in clover. In his flashbacks, every love is pure and every character speaks in complete Oprah’s-Book-Club paragraphs. There is glamorous travel and the pursuit of a heartfelt soulmate. There is trauma and trial, a serious injury, but heroic recovery. There is perseverance against the odds, and if you ever lose sight of those odds don’t worry, he’ll remind you. His pursuit of sponsorship, armed with nothing more than perfect genetics, good looks, a business degree from Yale, and well-connected friends and family, is given in heartbreaking style. If ever you are so unwise as to think the story is getting going you will soon be disillusioned by another stupid digression. He had a crush on the playground. He watched the Olympics. He went skiing at Whistler while his wife’s mother was sick. Fancy meditation retreats, world travel on a slender budget, a serious injury in Thailand, his difficult recovery and rather easier path to becoming a professional triathlete, relationships, Thanksgiving with his family, making love. What’s it like to sledge long distances in Antarctica? Well it’s very difficult and very painful and rather cold.

For what O’Brady is doing is telling a mythology about himself. The scant history is half-remembered grade-school stuff about Scott, Shackleton, Amundsen, and Nansen. There is little appreciation of the terrain he passes though, not more than three or four occasions in the whole book; one of the great joys of adventure literature is almost absent here, and the few moments when he records something memorable, such as when appreciates an untended airbase with the absurd little outhouse he had been desperately in need of hours earlier, but the use of which would compromise his unsupported status, are most of the book’s few good bits.

By all accounts, Antarctica is a very “samey” continent. To really write out the day-by-day impressions of sledging across featureless ice would be boring in the hands of anyone less than a master. Fiennes fills his book with history, geology, and above all his relationship with Dr. Stroud, told in the quite openly unfair way that marked Fiennes’s mindset at the time, mixed regularly with the acknowledgement that yes, Fiennes knows he was being unfair but that’s how he felt, that’s what the mind does on truly grueling expeditions with a partner. The best part of Fiennes’s book is when, after a particularly hard day on Stroud, the two are in the tent, Fiennes revving up to verbally tear Stroud to ribbons, while Stroud examines an infected abscess on his Achilles tendon. No good; he’ll have to operate. He sinks two syringes of local anaesthetic into his own ankle, surgically slices the abscess open, squeezes out the pus, and bandages the wound. With hardly a word, Stroud earns Fiennes’s silence.

O’Brady did not have a companion along to add human interest, and autobiography is not automatically bad. Grant him that grace. But his introspection is uncut narcissism, all self-absorption with no trace of self-reflection. He has no evident interest in Antarctica, that astonishing place. The only thing Colin O’Brady likes to talk about is Colin O’Brady.

His obsession with the psychological reaches the morally distasteful. After passing the South Pole, O’Brady has to cut his rations:

I was sitting on the sled, eating my reduced portion of ramen, when I thought of Henry Worsley’s descent into peril. I certainly didn’t know what his final days had been like, or the exact symptoms of his decline, but he’d clearly hit some dark corner of his mind and body, a place where something of Antarctica had confronted him or changed him. And that night, when I froze again in place, suddenly confused about lighting my stove, it struck me that perhaps Worsley, a giant of Antarctic wisdom and experience, had not known what to do when he hit that inflection point. Maybe he’d become locked in place, unable to choose or see a correct path ahead, and that’s what had turned a problem into a crisis.30

Lieutenant-Colonel Worsley had not “hit some dark corner of his mind and body,” he had developed peritonitis, and if he’d been an ambulance ride away from a good hospital he probably would have lived, but he wasn’t so he died. The kindest thing to say about paragraphs like this is that they are not meant to have any kind of literal meaning, that O’Brady is trying to let the reader into his anxieties that are as unreasoning and unfair as anxieties usually are, but in the text O’Brady gives us no hint that he meant anything other than… what that means. That O’Brady was too strong-willed to get peritonitis like Worsley? The mind recoils, the stomach churns.

Was the trip simply too safe? Never call it easy, it wasn’t that, but did too little go wrong? Your average polar adventurer has tales of dangerous chances, injury, and near-death experiences. O’Brady mentions crevasses more often as a metaphor than as a danger, which is not to be wondered at since he never encounters one. Outside the safety zones crevasses are probably the objective hazard of Antarctic sledging today. Radar and aerial spotting can find bad fields, but those techniques are not perfect and when sledging ice shelves or unimproved glaciers there’s no way to totally avoid crevasse country. When you encounter them, you simply must cross their fragile snow lids and hope they bear the weight of yourself and your sledge. If they don’t… you fall through, perhaps plunging fifty, a hundred, two hundred feet into the icy abyss. No gadget makes the fall shorter and no satellite messenger will save you from the sudden stop at the end. The only way to avoid them is to avoid ice shelf or glacier travel on anything but improved trail. By doing this, O’Brady gave himself a much easier time than his predecessors.

Sometimes he falls over. There are blizzards, but not many, and like the tears freezing on his cheeks the first day, the blizzards serve the dramatic purpose of making Colin O’Brady the right speaker for your company on Overcoming and Persevering. He’s so full of himself that even when he pretends he’s in peril he’s not credible. The epic he makes about an empty food bag blowing away must be read to be believed or, even better, not. If he was self-aware and ironic it could be charming, but nobody has been less self-aware in the history of adventure literature.

I don’t know where it came from, but I woke with a phrase. My alarm beeped, I pulled off the eye mask that helped me block the sun, and there it was, and it had to be said aloud. “Colin,” I shouted into my tent to the empty, cold continent around me. “You are strong! You are capable!”31

SHUT UP!

In the modern era, the distinctions32 got even finer grained, often relating to whether an effort on the ice was supported or unsupported by resupplies of food or fuel cached or provided along the route, and/or assisted or not by any means other than muscle. The Norwegian adventurer Børge Ousland in many ways defined the terrain of astonishing modern Antarctic feats, becoming the first person to cross Antarctica solo when he traveled eighteen hundred miles alone in sixty-three days from late 1996 to early 1997. Not only did he cross the entire landmass of Antarctica, but he also crossed the full Ronne and Ross Ice Shelves from the ocean’s edge. Ousland’s expedition, which had deeply inspired me, was unsupported in that he’d hauled all his food and fuel with no resupplies, but, importantly, assisted in that he’d used a parachute-like kite called a parawing, harnessing the wind to pull him across the ice. His team proudly announced that on one day with particularly favorable winds—parawing deployed—Ousland had sped 125 miles in only fifteen hours. A single-day distance unfathomable without wind assistance.33

Every word of that paragraph is true. Ousland gets credit for crossing the ice shelves, but as a bonus, rather than the historic expectation of what crossing Antarctica actually meant. The asterisk over Ousland’s wind assistance is a quarter of the text, and certainly, he was assisted, but the proportion of Ousland’s journey he spent manhauling without the wind is missing, since that might call attention to the fact that he pulled more days and more mileage with his own two legs than O’Brady, or Captain Rudd. The impossible first would be shown as not only possible but not even first. O’Brady tells a strategically-selected sort of truth.

Compare it to O’Brady’s own account of receiving assistance. The South Pole Overland Traverse is a 995-mile trail from McMurdo Station on Ross Island, across the Ross Ice Shelf, up to the Antarctic plateau via the Leverett Glacier, and across the ice to the American base at the South Pole; not a road, but a prepared track, maintained over the Antarctic summer by the United States. The route is smoothed, though certainly imperfect, and crevasses are filled in by bulldozers. The route is lined with flags, so even in whiteout conditions navigation is a non-factor. It is used by heavy logistics convoys and solo adventurers alike; in 2013, Maria Leijerstam bicycled 400 miles of it. Travelling the South Pole Traverse is as safe as Antarctica gets outside a building, and for this reason PECS considers not only using the road, but travelling on the Leverett Glacier at all, a form of support.

O’Brady took the South Pole Overland Traverse trail for almost 400 of his 900-odd miles; the New York Times reported their astonishment at both O’Brady and Rudd picking up their speed after the South Pole as if unaware their route had suddenly become artificial34. Small wonder he had nothing to write about. ALE, O’Brady and Rudd’s logistics company, seems to have required the easy way:

“But I have to tell you, Colin, that the route you can take through the Transantarctic Mountains is non-negotiable,” Jones said. “Leverett Glacier to the Ross Ice Shelf is the only solo expedition option. If you’re going to do this, that’s it. All the aerial mapping of the crevasse fields, the ground penetrating radar, everything supports this.” He paused for a second. “Lots of that work is thanks to you Yanks, since the US government uses that route to send a large load of gear from McMurdo, their coastal base, to resupply the South Pole station every summer. The South Pole Overland Traverse will already have come through for the year by the time you get there, so as a result the route won’t be completely pristine. You’ll see some flags and rutted tracks from their vehicles, but it’s the safest for soloing.”

I was silent for a moment, My research into the routes through the Transantarctic Mountains was preliminary, but I’d read accounts of expedition teams on other routes navigating through crevasse fields there and, while roped together, falling through the ice daily. The thoguht of being alone, unroped, with no one to pull me out of a bottomless crevasse was terrifying.

[. . .]

“I’ve been around for a while, Colin, a lot longer than you, and let me tell you, safe is good in Antarctica,” he said. “And the second thing is that any route, whatever it is, if it can be completed solo, unsupported, and unassisted, it will be a world first—no one has ever manhauled the landmass of the continent in that way.”

“No, no,” I said. “I’m happy to take the safest route that qualifies under the rules—and the route has historic precedent anyway, right? Felicity Aston went across on the Leverett in the opposite direction if I remember correctly, and she really inspired me.”35

Remembering that the PECS rules which qualified the South Pole Overland Traverse road as “support” were not in place when O’Brady was skiing, he is, once again, being honest to the letter. If he didn’t say he took the trail, he would have been accused of hiding it, so he mentions it—once, amidst fears of falling through glacial crevasses, a risk which he does not quite bother to mention had been reduced to near-zero, and justification that, it’s okay, this counts, really. The convoy already went through so the route isn’t being maintained for the rest of the year! When a hiker hears that the trail crew already went through this year he says “thank God!”; O’Brady tries his best to make it look like his odds have dipped but he has no choice. Besides, Felicity Aston did it! Never mind that Aston explicitly used support, of which the trail was only one component, using two air resupplies to keep her sledge weight below two hundred pounds.

O’Brady does not mention that he is skiing down maintained trail again for the rest of the book. He did his strict duty, and to call attention further to it might distract from the vital worship of Colin O’Brady.

Fast forward to near the end of the journey. It is Christmas Day. O’Brady has awoken in his tent, depressingly early in the morning, although this being the Antarctic summer the sun is fully up:

The sun glinted its red rays through the roof, and all the worn, frozen, and frayed pieces of my life gently swayed around me and over my head, and when I checked the inReach there was a text from my dad. His words underlined everything I’d just been thinking about choices and darkness and light.

“Merry Christmas,” he wrote. “Remember the most important thing.”36

What do you think the most important thing is to remember on Christmas Day? Perhaps you’re not a Christian, but you thought it. Not Colin O’Brady. The most important thing, it turns out, is to have fun. It never occurred to him there might be any other meaning. “Infinite love!” O’Brady shouts as he skis down his government-maintained path, serene in the knowledge that not even a blizzard will let him get lost, not with his personal divinity, and perhaps the well-marked trail he’s skiing, though he forgets to mention that bit. I believe in Colin O’Brady, conqueror of heaven and earth, and in the United States dollar, his only son, our Lord.

It is essential, above all, that Colin O’Brady be the man who overcame, that did the impossible, that you want to book for a speech on overcoming adversity, and this man can talk about himself for thirty minutes at a time no problem. If the odds aren’t stacked that hard against you, ratchet up the psychodrama until you can convince someone they were, and that way you can look on the once-heavy sled as a friend, take the once-dreadful blizzards as just nature’s passing tempest, and make mountains out of molehills even when literally coming down mountains.

Fiennes’s book ends with detailed appendices. A thorough gear list, with weights, that stand with any ultralight hiker’s spreadsheets. A catalog of medical complaints, and the course of their recovery back home in England. A comparison of ration plans, where known, with previous expeditions. The preliminary reports of Dr. Stroud’s nutritional and muscle-strength analysis, accumulated by painstaking measurements on tiny electronic scales, with painful muscle biopsies, and the retention of urine passed with the help of heavy water to identify tell-tale isotopes in their bloodstreams. Navigational details for each day’s march. Technical information on the practical points of radio communication in the Antarctic. Thanks to the support team and a list of sponsors. A natural and geological history of the continent. A glossary, bibliography, and index. Allowing for the passage of thirty years (Lawrence Howell’s radio observations are sadly practically obsolete), if you wanted to fire off your own Antarctic expedition, you’d have a good deal of starting research right to hand.

O’Brady was hardly on a research expedition, an index is less necessary in an e-book, his acknowledgements are as generous as could be wished, and a bibliography would be superfluous in a narrative that shows no sign of ever having come near another book. So his story ends with his rapturous return home as the conquering hero, and how he waited for two days at the finish, on the inland edge of the Ross ice shelf, to generously reunite with his great adversary, Captain Rudd, a gesture of sportsmanship that makes his TV studio hostess tear up. He neglects to mention that, by sharing a plane with Rudd instead of chartering his own, he saved about $50,000.

In 2011–12 the Norwegian soloist Aleksander Gamme and the Australian duo of James Castrission and Justin Jones (universally known, being Australian, as Cas and Jonesy) raced from Hercules Inlet to the South Pole and back. This is a short route without an ice shelf but at least it didn’t have a trail on it; what matters is that Gamme, well ahead of Cas and Jonesy, stopped before the finish line for four days to let the Australians catch up, then finished the journey together in equal time. Gamme could have won, sat at Hercules Inlet, and waited for the plane like O’Brady did, but instead he made a point of waiting for his competitors so they could finish together and, in line with that sporting gesture, the record shares the honours between them. That is sportsmanship. Winning a race and waiting for the other competitors to come in so you can split the ride is not really on the same level, but O’Brady, true to his nature, wants you to think it is. Infinite love, right?

Care to cross the Antarctic yourself? Fiennes and Stroud’s sleds weighed 27.5 pounds each empty, with traces. They carried 255 pounds each of food and 72 pounds each of fuel. They had three cameras, ten still-photo film rolls, nine video tapes, and 12 camera batteries, total 12.5 pounds. Their sleeping bags, all in, were 13.5 pounds each, and their windsails 11.5 pounds each. They carried 21 pounds in radio gear, a 10-pound Sarsat beacon with batteries, two six-pound Magellan GPS navigators, and two one-pound PLB beacons. With modern materials and electronics, you know where you’ll bust down below their 485-pound average starting weight.

What do you want to know from O’Brady’s expedition? Um, he mentions early on that his sled was second-hand. There are books where you talk about an expedition, and books where you talk about how great you are. When Ranulph Fiennes writes about crossing most of a continent, he wants to put you in his boots, with his troubles, and his experiences, and his knowledge. Colin O’Brady, well. His book is extraordinarily bad. Given the artificiality of his “record,” so glaring that an organization was set up to hinder such claims in the future, it would have been so nice if he could have earned our respect by his writing. But always unlikely.

- Out of print, but easily available used.

- Not out of print, but I’ll be damned if I post a link that might lead to one more sale of this thing.

- Polar Expeditions Classification Scheme. “PECS | Aid.” pec-s.com. Accessed July 29, 2024. https://pec-s.com/guidelines/aid.

- Which is not, in the usual sense, really an island at all, but a raised bit of the ice shelf because the sea floor is a little higher in that area.

- Sir Ranulph Fiennes. Mind over Matter: The Epic Crossing of the Antarctic Continent (London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1993), 19.

- Adventure Network International, now Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions, the largest private logistics and adventure tourism company operating in and around Antarctica.

-

Fiennes, Mind over Matter, 224.

EDIT: August 10, 2024: that Fiennes wanted his insurers to agree that death was inevitable without an evacuation is obvious in the text; it is, indeed, literally stated, with reasons for his concern and justifications for his pulling the cord anyway. It occurs to me only on rereading this article, however, that Stroud clearly felt the same way to provide, on his authority as a medical doctor, such worrisome quotes, particularly as regards his own condition. The rest of Mind over Matter, as well as the rest of his expedition history, clearly proves that Stroud was not one to suck it up and write lies for his expedition leader. There are uncited quotes in the wilderness press that Stroud thought he and Fiennes had left their crossing only part-finished, and if he said so that was very wise of him, for he was right. But Stroud fought on with Fiennes on a few subsequent adventures, indicating no mistrust, and the shape of Stroud’s analysis of their state on evacuation supports the original point: Sir Ranulph and Dr. Stroud bailed because it was that or die, not because that was their preference.

- Fiennes, Mind over Matter, 243–4.

- Wikipedia. “Ranulph Fiennes.” Retrieved July 28, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ranulph_Fiennes&oldid=1231725988.

- Sir Ranulph Fiennes. Mad, Bad & Dangerous to Know: The Autobiography (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2008), 192–3.

- q.v. Fiennes, Mind over Matter, 245–6; of Fiennes and Stroud’s 485-pound starting loads, 255 pounds (52.6%) was food and 72 pounds (14.8%) was fuel.

- Though less so for Stroud, who is uncharacteristic in this story in having a real job to which he was, and as far as I’m aware is, devoted. One gets the impression from reading Fiennes that for Stroud a good proportion of the point is having real-world scientific data of the human body in extremis he can bring home.

- For much of the summary of the next 15 years in polar travel I am indebted beyond words to: Damien Gildey. “Crossing Antarctica: How the Confusion Began and Where Do We Go From Here?” Explorersweb, January 9, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2024. https://explorersweb.com/crossing-antarctica-how-the-confusion-began-and-where-do-we-go-from-here/.

- Fields, Jenn. “Crossing Antarctica: Boulder’s Ryan Waters, partner first to complete trek unassisted.” Colorado Daily, February 2, 2010. Accessed July 30, 2024. https://www.coloradodaily.com/2010/02/02/crossing-antarctica-boulders-ryan-waters-partner-first-to-complete-trek-unassisted/.

- “The Journey.” Shackleton Solo. Accessed from the Internet Archive July 29, 2024. https://web.archive.org/web/20180115181223/http://shackletonsolo.org:80/journey/.

- Some guy who I assume is not the obviously-intelligent Colin O’Brady. “Antarctica 2018.” Colin O’Brady. Accessed July 28, 2024. https://www.colinobrady.com/expeditions/theimpossiblefirst.

- Absolute justice requires me to record that Fiennes’s Mind over Matter has a few “Antartica”s as well, but it’s one thing as an occasional typo in a 30-year-old book and another in a web page of the spell-check era that can be updated any time. Moreover, while I did not count Fiennes’s “Antartica”s I am confident it is closer to five in 300-odd pages than to 11 in a few paragraphs.

- The Wired article is still online at https://www.wired.com/2016/02/people-cross-antarctica-all-the-time-its-still-crazy-hard/. Typo aside, O’Brady’s website’s use of the quote is justified, since the author was referring to Worsley coming 30 miles short due to peritonitis as obvious proof that if you sledged 950 miles you’d starve to death.

- “Impossible First.” Colin O’Brady. Internet Archive snapshot of January 1, 2019. Retrieved July 29, 2024. https://web.archive.org/web/20190101141922/https://www.colinobrady.com/theimpossiblefirst.

- Fiennes, Mind over Matter, 255.

- Wikipedia. “McMurdo Station.” Accessed July 31, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=McMurdo_Station&oldid=1235459297.

- Colin O’Brady. The Impossible First: From Fire to Ice—Crossing Antarctica Alone. (New York: Scribner, 2020), Kindle, loc. 108.

- As it happens, according to Captain Rudd, he didn’t know his expedition would be a race until five days before his departure; see Tillard, Patrick. “My solo crossing of Antarctica.” Shackleton, January 19, 2021. Accessed August 1, 2024. https://shackleton.com/en-ca/blogs/antarctica-now/interview-louis-rudd. He was in the same boat as another famous British Antarctic captain, though a naval one, as Captain Scott only learned Roald Amundsen would be racing him on his way to the Antarctic, long after it was too late to do anything about it.

- O’Brady, The Impossible First, loc. 1239.

- For example: Apsley Cherry-Garrard. The Worst Journey in the World (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 198.

- Fiennes, Mind over Matter, 53. All emphasis as quoted.

- Fiennes, Mind over Matter, 54.

- O’Brady, The Impossible First, loc. 403.

- O’Brady, The Impossible First, loc. 452.

- O’Brady, The Impossible First, loc. 3067.

- O’Brady, The Impossible First, loc. 590.

- Between types of Antarctic expedition.

- O’Brady, The Impossible First, loc. 774.

- “Despite the altitude, and all of their pain and obstacles, O’Brady and Rudd seem to be growing stronger, as counterintuitive as that sounds.” From: Day 46, Dec. 18, Tuesday. “Tracking the Race Across Antarctica.” The New York Times. Accessed August 1, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/12/18/sports/antarctica-race-tracker-map.html.

- O’Brady, The Impossible First, loc. 2908.

- O’Brady, The Impossible First, loc. 3547