At a used bookstore in Coombs, of all places, I first met two of the old Don Beers cycle of Canadian Rockies trail guides, The World of Lake Louise and Jasper–Robson: A Taste of Heaven.

Beers is a retired Calgary teacher who began exploring the Canadian Rockies in the 1950s. “Exploring” is the right word; not just hiking (though he did plenty) but coming to know people, places, characters, and histories to a depth equaled by few and equally-communicated by none. Those were good years: the trails were cared for, horses and hikers alike roamed from the border to the Kakwa, wardens lived at their cabins sharing experience in person, and the second-generation pioneers, the people who knew the people who opened this vast natural wonderland, were around to share their fathers’ stories, a living index for archival research at which Beers became unusually expert for a public school teacher.

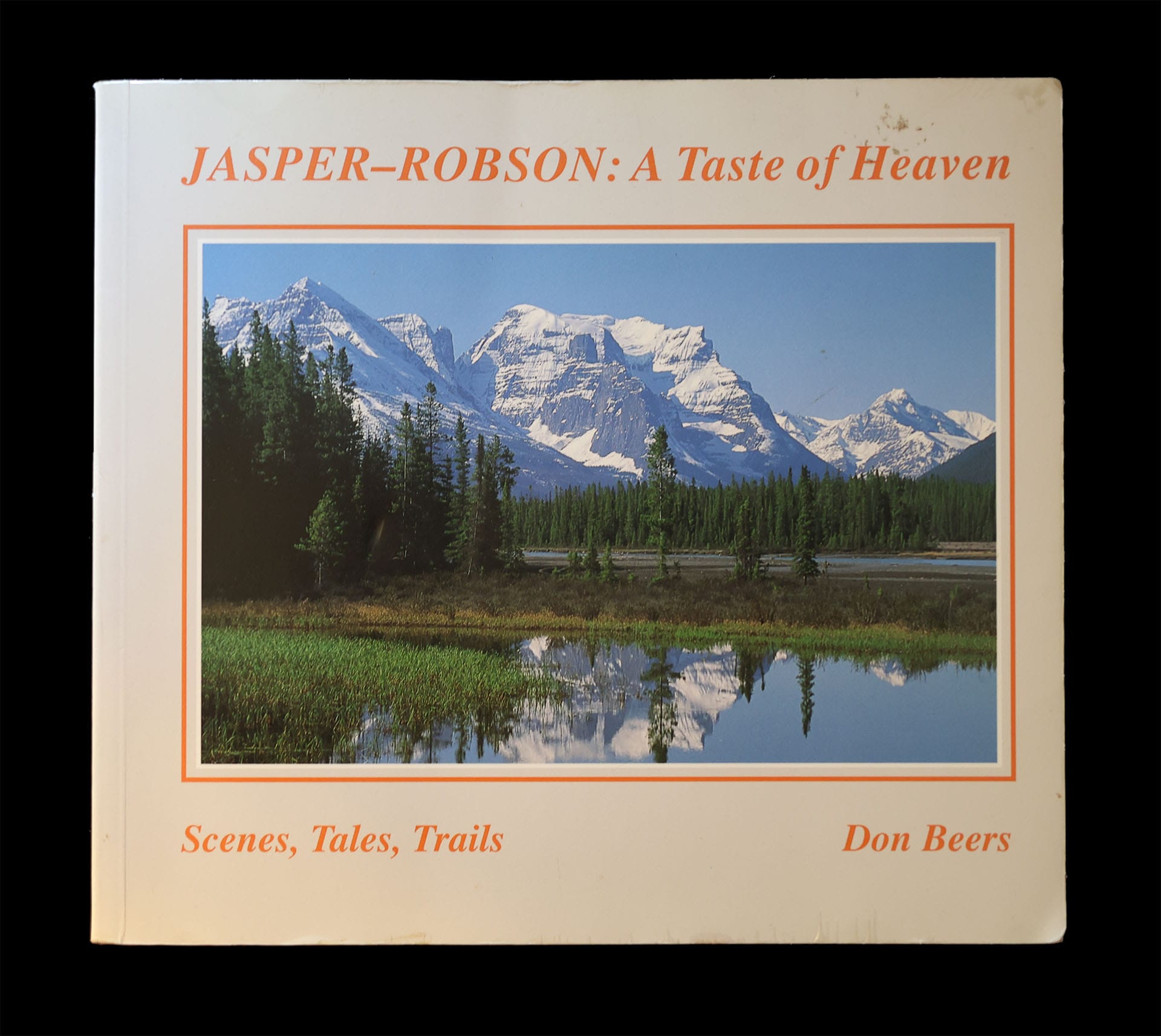

It was thirty years before Beers put pen to paper. His 1981 debut, The Magic of Lake O’Hara, was conventional, but 1989’s The Wonder of Yoho began what became a short, priceless series. Lake Louise (1991), Banff–Assiniboine: A Beautiful World (1993), and Jasper–Robson (1996) followed, then Beers put the pen down, returned to his family and the trails, and let his words, his photos, and the stories and history he collected speak for themselves.

Though not exactly rare, these books were mostly self-published and are rarely stumbled upon. Many tourists dipping in at the gift shops were probably bored by the historical and geographic passion, but those who felt sympathy never put them down, and have evangelized the books long after they ceased to be current. They are objets d’art; even if someone had the ability to create books like this, they’d never be commercial propositions, and they are far more labours of love than an attempt to make the author famous.

Self-promoting authors are not new to the Internet age; publishing is inherently egotistical and self-promotion is good-feeling good business. Not Don Beers. You won’t find him seeking attention for anything other than the mountains. Decades of experience and research were accumulated in the vessel of his memory before he poured it onto the page, clear as mountain water, and there they have stayed, the best books of their type ever written.

Most trail guides take very practical names: The Canadian Rockies Trail Guide, Backpacking in Southwestern British Columbia, Hiking the West Coast of British Columbia, a library of books that are exactly what they say they’ll be. Beers shoots for romanticism. Jasper–Robson: A Taste of Heaven, subtitled Scenes, Tales, Trails. The four major books are 9×7 and packed with perfectly-reproduced colour photographs. You might not know from the cover that they are practical trail guides, but his descriptions are thorough, with distances, elevations, campsites, and guidance, and in their day were probably invaluable. To the modern reader they are conspicuously pre-GPS (“hike 41 paces…”) and the latest descriptions are now thirty years old, so obsolescence has intervened. But the scenes, tales, and trails are as good as ever, and make the books must-haves even today; Beers’s evocative titles are precisely as accurate as everyone else’s straightforward ones.

If you want to catch some of Beers’s manner look at what as far as I am aware is his only other published work, a 2010 article in the scholarly Alberta History journal of the Historical Society of Alberta1. The two subjects of the article, Sir James Lougheed and Eugene Bourgeau, are now obscure, as indeed are some of their mountain memorials. I cannot forbear quoting one of Beers’s footnotes at length:

To this day, there is an unnamed pinnacle over 9,500 feet high adjacent to Mount Bourgeau. To get to their Banff cabin, the Lougheeds had to cross the Bow River bridge. From this bridge, the 9,500-foot summit is one of four impressive peaks of the Massive Range seen on the western skyline. The unnamed summit is north-west–not north-east–of Mount Bourgeau but seeing the skyline peaks of the Massive Range in line, it is unlikely that a viewer would first stop to calculate the points of the compass. From south to north the four peaks are: Mount Bourgeau, the unnamed peak, Mount Brett, and Pilot Mountain. Could this unnamed peak be the summit the family first thought had been chosen when Lady Lougheed accepted the honour? If the Board had in fact intended to offer the 9,500-foot summit, would the family have been satisfied with the choice? There is no evidence that the Lougheeds were ever aware of the precise identity of the 8,888 foot outlier of Bourgeau. The Lougheed House Conservation Society fonds (see note 11) include a letter from Clarence Lougheed to F.H. Peters stating that Peters had mentioned Mount Bourgeau and Mount Brett. Peters did not mention Brett in his letter, but the young Lougheed’s letter might suggest that the family were indeed thinking of the 9,500 foot unnamed summit, which is between Bourgeau and Brett, instead of the 8,888 outlier of Bourgeau.

About twenty years ago, while browsing the 1926 map Banff and Vicinity in the Whyte Museum’s archives, I noticed a Mount Lougheed shown near Mount Bourgeau. I had never before heard of this summit. I stepped outside to look for Mount Lougheed. Although I saw it, I didn’t recognize it because the top of the mountain blends into the strata of Mount Bourgeau, which overshadows it. I guessed Mount Lougheed to be the shoulder on the north east side, where the ridge rises slightly. I was close, but that shoulder is 500 feet lower than the highest point on Mount Lougheed. I have since “seen” Mount Lougheed countless times from Banff and from the top of Sulphur Mountain, but always Bourgeau’s camouflage deceived me. I never guessed that Lougheed’s flattened pyramid, visible but insignificant, was once named a mountain. Finally, while hiking back from Rock Isle Lake I realized that a low mountain like ridge ahead was the elusive Mount Lougheed. Later, looking at old photos I finally recognized it, but I was not impressed. I have never met anyone who identified the 1926 Mount Lougheed.

There’s the enduring value of Beers in two paragraphs: digging up ancient maps and fonds, tracing names back to stories, seeking and eventually finding the connection between geography, history, and aesthetics, and sharing it until you can almost see it. What Don Beers does better than anyone is reproduce what hiking the Canadian Rockies backcountry feels like. Once you’re away from the modern tourist trails, it’s more than just beautiful. It feels old. There are always reminders that most of these trails were well-established and well-loved before your grandparents’ time. The atmosphere is unlike anywhere else, even obviously, overtly historic routes like the Chilkoot Trail. The signs, the air, the trees exude history, and no book will ever cover it, but Don Beers brings that unique feeling to as much life as words will allow.

Even The World of Lake Louise, where trails are as well-trodden as any in the world, is replete with this. Do you really need to know that Peter Spear, Jim Gardner, and Harry MacPherson were treed by a grizzly while camping on the Red Deer River’s Shingle Flats? Of course not, but how much more memorable it is than the usual blasé “grizzlies frequent this area.” Beers devotes two and a half pages of text to the Plain of the Six Glaciers and Lake Louise lakeshore hikes, which require no more guidance than “go to the crowd and follow it.” But we hear about the tame marmot of the Smith family at the Lake Agnes Teahouse, the hair-raising adventures of experts and lucky escapes of tourists in the infamous Deathtrap between Mount Victoria and Mount Lefroy, and the history of those six (really, as far as Beers can tell, seven) glaciers. If crowds make you reluctant, Beers tells us that Sharon Wood, the first North American woman to climb Mount Everest, called the Plain of the Six Glaciers her favourite place in any mountains, then prints beautiful photos to back that up2.

When Beers writes about Jasper’s South Boundary Trail, he writes about the now-defunct route from Jacques Lake, but more than half the two-page spread is given over to tales from the trail, about Ed MacDonald crawling away from a near-fatal grizzly attack in 1940, Stuart Taylor repairing his pants with a fork, and the tragedy of John McGillvray, among others. You can find out how to navigate the changed trail elsewhere; the history, irreplaceable unless you can repeat Beers’s work of listening, reading, watching, and hiking in the old days, is what keeps us turning the pages.

History is everywhere. On page four of Jasper–Robson, Beers’s late friend, retired warden Frank Camp, is photographed lounging at Glacier Pass, today an unmaintained spur of the undermaintained North Boundary Trail, the backcountry’s backcountry, in double denim; jeans and jean jacket. Sure, Camp was on horseback and the weather was fair, but it is literally a look into another era, the old Metis guide inured to hardship, when being cold and wet didn’t mean the same thing as it does to today’s hikers panicking about condensation. Camp was pushing seventy when that photo was taken, and damned if you can tell. Even the trail-hardened outdoorsmen don’t look the same anymore, but there is what they used to be, in Kodak clarity that must have cost a fortune to print.

In July 1987 a grizzly bear treed twenty-four campers and ran riot through the Lake Louise area; thanks to courage and resourcefulness on the part of the campers, and the bravery of wardens on horseback, nobody but the bear was killed or seriously injured. Beers relates the tale in detail with a photo and the lively testimony of witnesses. Why do you need that within a description of the Kingfisher Lake trail, a literal three-minute hike from a parking lot within walking distance from Lake Louise Village? Because it’s a good story, that’s why. Each book ends with pages of uncut history about the area, the people, and the events that Beers couldn’t work into the trail narratives but had unearthed from archives, forgotten books, and old friends. Three pages on Walter Perren, the last professional guide of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the first climbing instructor of the Canadian park warden service, serve no other purpose than rembering a character Beers met and admired. They are treasures.

Lest one focus too much on the romance, Beers is also very clear when the romance is missing. By the time he became an author his love affair with the Canadian Rockies was fully mature, it was hearty and reciprocated but he had no doubts about his bride’s blemishes, so he happily tells us of such wonders as Merlin Pass (“one of the very few mountain destinations I take satisfaction in knowing I will never have to go to again”), Moosehorn Lakes (“expect a rough trail with faint and overgrown sections, beaver swamps, and [30-odd] fords”), and Disaster Point (which lives down to its name).

Such clarity and perspective makes his enthusiasm for the places he loves contagious. You can tell the depths of that love because he never settles for plain assertions of how pretty it all is. Another lengthy quote from his description of upper Blue Creek valley, off Jasper’s North Boundary Trail:

Few hikers visit this remote area. Yet outfitter Tom McCready, and warden Dave Carnell, who know the Park well, have told me that this is their favorite part of Jasper.

The valley is renowned for its scenery. Multi-hued blue lakes feed Blue Creek. The sheer limestone faces of the Ancient Wall rise to the north. The imposing Natural Arch was discovered by outfitter Fred Brewster who was searching for a route to connect the Sulphur River with Snake Indian River. Hiker-historian Lawrence Burpee suggested calling the reddish mountains south of Blue Creek “Sunset Mountains,” a name now used for the northern summit of the Ancient Wall.

Bighorn sheep, caribou, moose, wolves and grizzly bears frequent this remote wilderness region. Blue Creek, a glacial stream, is often silty grey. Gillean Daffern suspects its name may, in fact, derive from the monkshood, which turns the high meadows blue by late July. [. . .]

Near the site of Natural Arch Horse Camp, Curly Phillips built a cabin where he trapped before this area became part of Jasper Park.

From pioneers Brewster, Burpee, and Phillips, to contemporaries McCready, Carnell, and Daffern3, Beers shows us the depth of a part of the park rarely seen by even dedicated backpackers. We are admitted to its history, we do not need to take Beers’s word that it is a grand and ancient place. It’s more interesting, informative, and valuable than a thousand paragraphs of personal impressions. “Ancient Wall,” “Natural Arch,” they sound remarkable (and are); those names, and the hardened men who inspired them, flying out in almost-disconnected sentences just because Beers couldn’t bear not to share them. They mean more than even his many glamourous photos.

For readers boasting even a cursory familiarity with the Canadian Rockies backcountry, Beers comes closer to evoking that being-there feeling than any other author, of trail guides or anything else, has ever done. It’s not because he’s a poet. Bluntly, Don Beers writes like a schoolteacher: short paragraphs, simple verbs, basic structure, limited adjectives, and the occasional indulgence of a semicolon. The pioneers he quotes have more style than he, but he quotes them freely. A Don Beers book is last of all about Don Beers; there is no solipsism. This does not reach to false modesty; if Beers encountered something interesting himself, he will say so, but his sole authorial purpose is to be a conduit for all that makes the Canadian Rockies so lovable.

When another Rocky Mountain guidebook legend, Brian Patton, published his tribute to Beers’s work in 2014, Beers’s daughter and granddaughter left lovely comments but though Patton certainly knew Beers (he gets a credit in Jasper–Robson) there was no dragging the author himself into the limelight. Which is appropriate. You can read all his books and hardly get to know Don Beers at all. But boy, will you get to know the Canadian Rockies, and then you’ll go explore them yourself. I’m sure that was exactly what he wanted.

- Beers, Donald. “Lougheed and Bourgeau: mountain names remembered.” Alberta History 58, no. 3 (Summer 2010), 21–26.

- Incidentally, Beers’s text says that Wood was the first woman to climb Everest, period, which she wasn’t; that was a Japanese named Junko Tabei in 1975. Tabei was also the first woman to conquer the Seven Summits and is fairly well-known. He would have got it right if he looked it up, and Beers was always looking things up, but he wasn’t that interested in the Himalayas. The Rockies were his outdoor passion and the rest of the world was colour commentary. I find this rather telling, and rather lovely.

- Among other achievements, Daffern is the author of the canonical hiking guides for the Kananaskis country and, with her husband Tony, founded the well-known Rocky Mountain Books publishing house. Beers gave the Dafferns Rocky Mountain Books’s first goat logo, while the Dafferns published Beers’s early work and Gillean contributed photos to Jasper–Robson. The publication history of Beers’s books is a bit hard to trace but that one at any rate was not published by the Dafferns, so Gillean contributing several beautiful photos to what might fairly be called a rival project also says something wonderful.