Jasper National Park’s backcountry has never been more popular, and never harder to enjoy.

Backcountry trails in the park were at their height in the 1980s and 1990s. Usage was relatively low compared to the decades both before and since, but the trail network was over a third larger and generally in better shape. There was literally a hundred bridges, and it is said, perhaps exaggeratedly, that you could hike a hundred miles without getting your feet wet. Trails now considered adventurous low-water-season hikes were in regular use all summer, and the backcountry camper could have as much, or at little, privacy and challenge as he wanted.

Although Parks Canada hems, haws, and chooses their data carefully when the subject comes up, the fact is that more people than ever are using fewer backcountry trails. To be sure, backcountry campers are by-and-large white and by-and-large spend little money in town except at the bar, so are unfashionable visitors, but we are in an unprecedented boom of backcountry popularity which the park is content to treat with, at best, benign neglect.

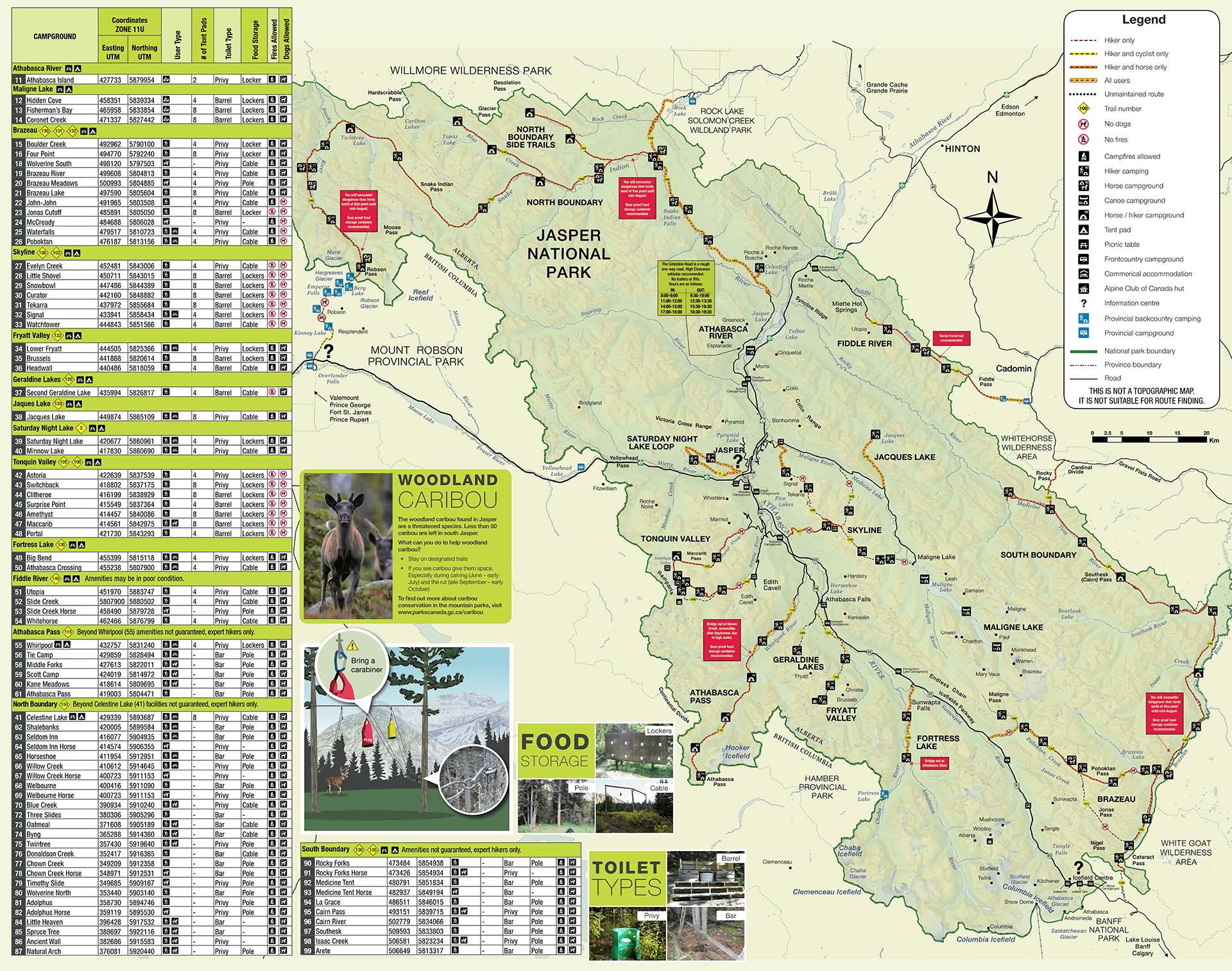

Parks Canada today documents about 775km of trails relevant to the backcountry hiker. This is the largest Jasper’s official backcountry trail network has been in over a decade, because the 47.7km Maligne Pass trail was formally re-opened, not that it helps any. Apart from Skyline, those kilometers are less accessible to horse and hiker than they were before. The Tonquin Valley has been closed to horses and lost its lodges and even the Brazeau Loop, one of the few trails Jasper cares about, has been for serious hikers only since a bridge went out in 2022.

What does this really mean? A couple of wonderful projects, the Parks Canada History Archive and the Canadian Backcountry Trails Preservation Society, have archived what Jasper National Park’s backcountry used to look like. It’s gotten a lot worse. Everyone who’s been there knows that. But it’s also gotten a lot smaller.

In a 2023 article, the state broadcaster very generously said Parks Canada showed “a slight increase of backcountry users now compared to a peak in 1978.” That 1978 peak is around 27,500 user-nights. In 1974, the nearest year for which a map is available, there were about 550 miles of official, acknowledged backcountry trail in Jasper National Park. There are now about 482 miles of trail, and in 2023, there were 32,951 backcountry user-nights1. In short, backcountry use has increased about 20% over the previous record high, a peculiar definition of “slight,” and trail miles have decreased about 11% from their previous low. Jasper’s backcountry is, substantially, the busiest it’s ever been since records began, and even busier per day when one considers how many hikes are how strictly for after August.

From 1938 to 2019, all distances are based off the official Jasper National Park backcountry trail map for that year. The large-scale Jasper National Park map has not been updated in six years and contains important omissions, so 2025 is based off that and the current park trail descriptions2.

| km | mi | km | mi | km | mi |

| 1001.5 | 622.3 | 892.8 | 554.8 | 1185.5 | 736.6 |

| km | mi | km | mi | km | mi | 755.8 | 469.6 | 733.5 | 455.8 | 775.4 | 481.8 |

| km | mi | km | mi | km | mi | km | mi | km | mi | km | mi |

| 1001.5 | 622.3 | 892.8 | 554.8 | 1185.5 | 733.5 | 755.8 | 469.6 | 733.5 | 455.8 | 775.4 | 481.8 |

The growth since 2012 consists almost entirely of the Maligne Pass trail. Parks Canada deactivated this trail, along with many others, in the 2010s, but in 2023 re-added it to the active trails list. It remains unbridged and largely unmaintained, and each of the campsites in it has a limit of one party per night. The primary reason for its reactivation seems to be that Great Divide Trail hikers were using it anyway, and it is easier for both the park and the hikers to manage it as a set of campsites rather than as a random zone3. There’s been no change to the neglect of the trail. Booking trails ordinary people want to hike remains awfully difficult.

Skyline and the Tonquin Valley are the only three-day or longer backcountry trails in Jasper without serious river fords most of the year4. Practical Skyline itineraries sell out on opening day every year. The Tonquin has more campsites and is hikeable for more of the summer, so mile-munchers can usually scrape something together, but anything in August booked after opening day would require a 20km-over-a-pass day between Maccarib campground and the Portal trailhead, which is a very, very solid day’s work for the ordinary hiker. The Brazeau, the usual third of Jasper’s three maintained backcountry trails, has been out of action as a loop for civilians since 2022 when a bridge washed out5, but even so, the most scenic weekends to check out the Jonas Cutoff are booked solid.

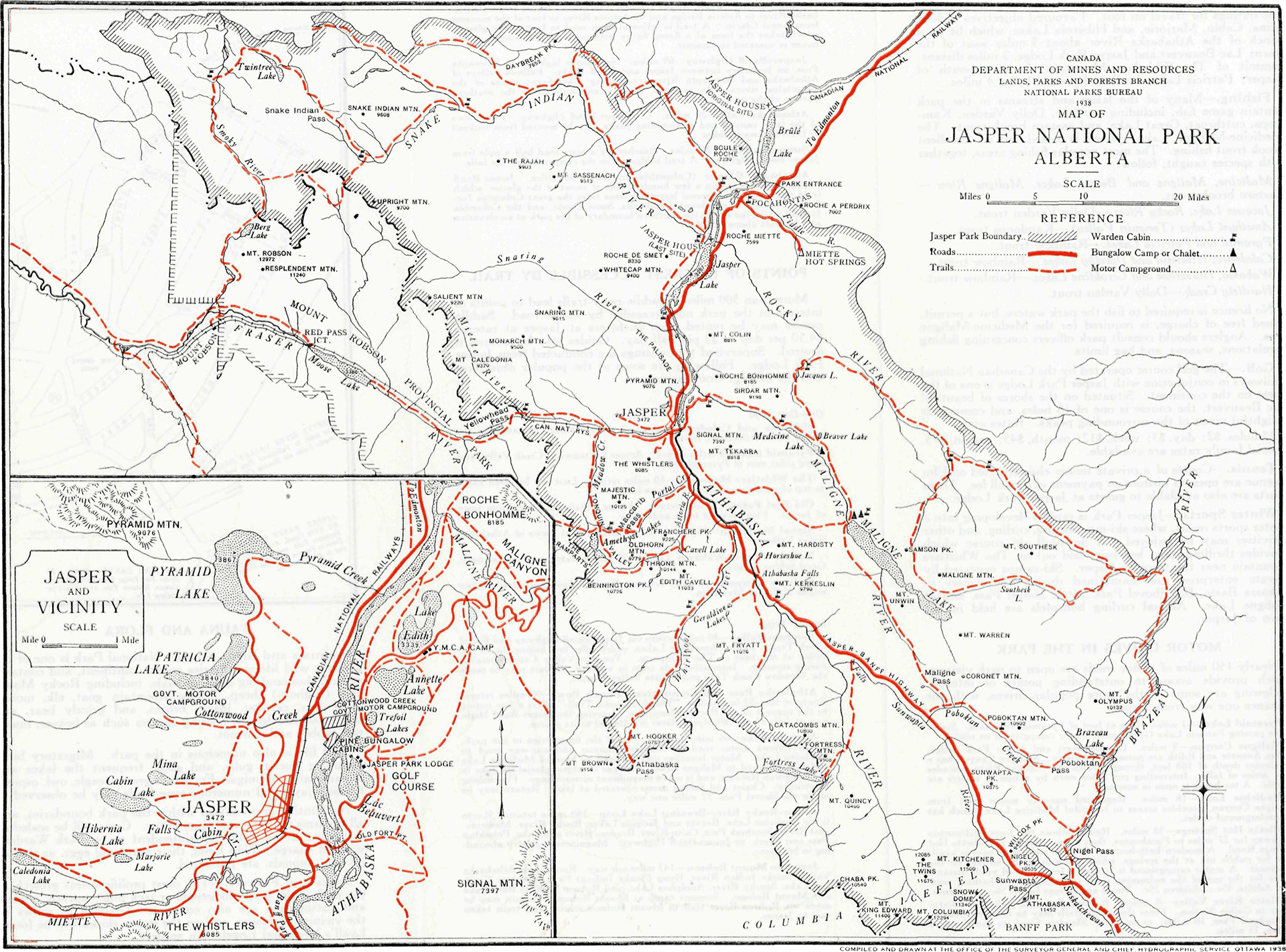

Most of Jasper National Park’s trails date back centuries, to the fur trade and the first railway men carving trail to captivate the tourists. A 1938 map is, even today, almost recognizable.

There are a few long-time trails, like Moosehorn Creek–Wolf Pass, that survived for decades but not to the twenty-first century. On the other hand, there’s a weird thing on the North Boundary, six miles or so between the Moose River and about what is now Oatmeal camp via Campion Creek, that was on the maps until 1962 and off them by 19646. Some familiar favourites aren’t quite right. The Saturday Night Loop is more like a Friday afternoon fishhook to just one of today’s three lakes. Skyline looks off, doesn’t it; it takes a good squint to realize that trail breaks off at what is now Curator campground before descending what we now call the Wabasso Trail through the Valley of Five Lakes into town, avoiding the famous Notch entirely. Important roads, such as the Celestine Lake Road, Snaring Road, the Edith Cavell and Marmot Roads, and for that matter half the bloody Yellowhead Highway, don’t exist yet, though there are trails on their routes and very interesting that ride to Moose Lake would have been.

As is not to be wondered in a time when relatively few of Jasper’s tourists got there by car, trails in this era were mostly for equestrians. This probably accounts for the truncated Skyline: the Notch would be impassible to horses. M. B. Williams’s Jasper Trails, an official park guide of the 1930s, routinely informs you where your ponies can be left or met, and includes some formidable trip ideas such as a 200-mile, 25-day ride between Jasper and Field, today a three-hour drive. Williams assures us that, though difficult and not for the inexperienced, “this trip has been made by a number of ladies”—the M in “M. B. Williams,” by the way, stood for “Mabel.”

But look at what is there. The North and South Boundary Trails are both missing their current standard entrances, at Rock Lake and Rocky Pass7, but otherwise it looks like they have hardly moved an inch. The Tonquin Valley is missing its side trips and alternate routes but there’s no mistaking its main line, and Athabasca Pass looks like it did to David Thompson and to the hiker of today, give-or-take the dated spelling “Athabaska.” There’s a trail to the Geraldine Lakes, there’s a trail that doesn’t really look like it’s going to the Fryatt Valley but probably is. There is no inaccuracy on the Brazeau Loop after 90 years: the small scale means even the warden cabin might be in the right spot8. Some trails have been added since 1938, and some turned to road, but the main changes have been removing them altogether, even on a relatively small half-page map devoid of topographic detail.

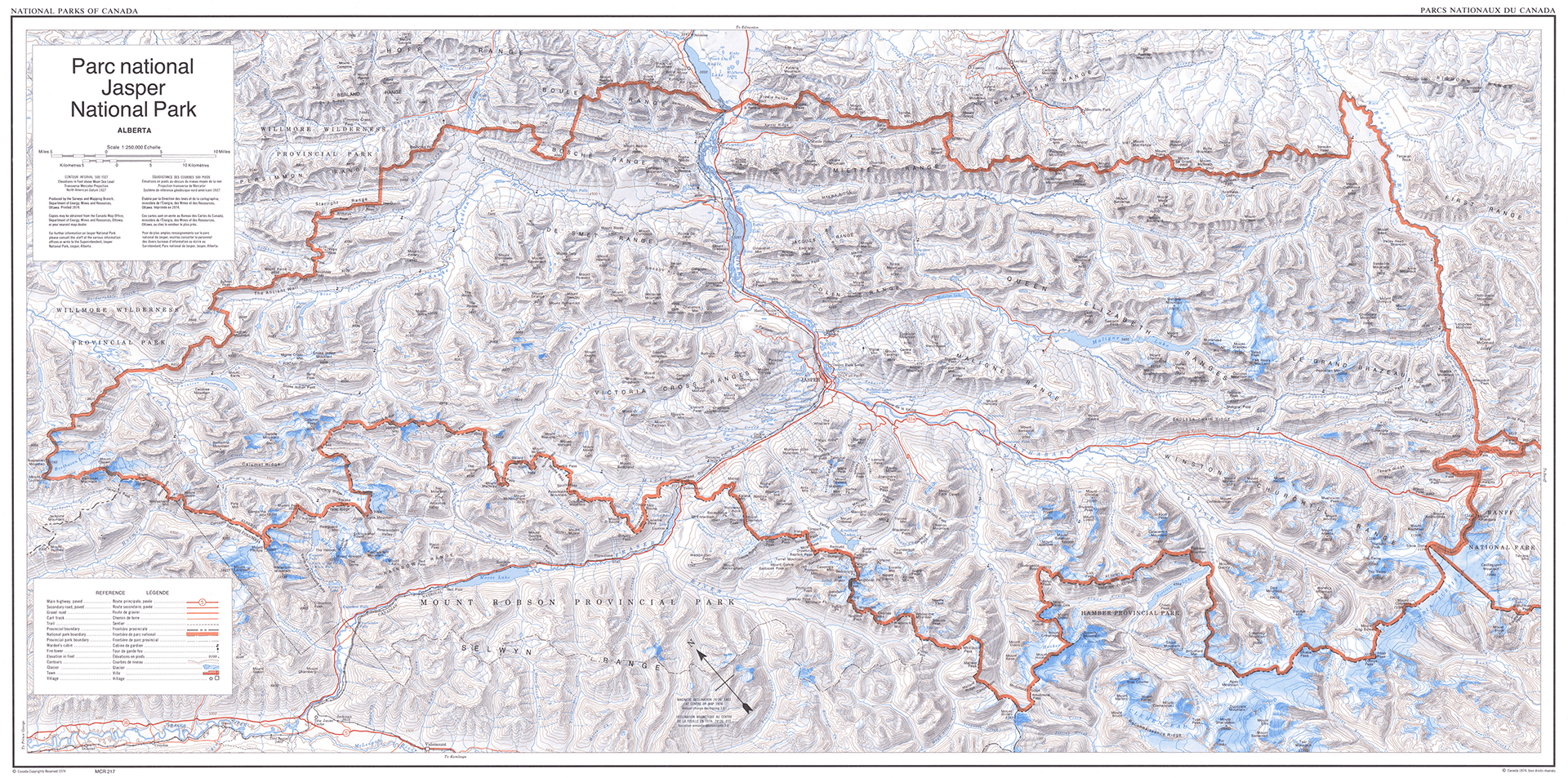

The earliest large-scale map suitable for navigation, or at least suitable for navigation if you travel back in time fifty years, available is that of 1974. It is an odd thing.

In 1974, probably to make it easier to print, they didn’t put north on the top of the page, and that eccentric decision sums this map up.

There are two points where I am almost sure the map is mistaken. The Athabasca Pass trail ends around Tie Camp, rather than go on to the pass, and the Geraldine Lakes trail is entirely missing (though the Geraldine Lookout day-use trail is present). The 1978 second edition of the Canadian Rockies Trail Guide mentions both with no special remarks. If I would have made an exception to my “if it’s not on the map, it’s not in the statistics” rule, it would have been these two, adding almost 45 kilometres to the year 1974.

It omits trails present everywhere else and also adds some present nowhere else, like a Grindstone Pass alternate to Wolf Pass or a break in the Fiddle River trail between Fiddle Pass and the upper Whitehorse that may be real but is somewhat hard to fathom. Many seeming-oddities are legitimate. The Watchtower Trail, today a side route to Skyline, in 1974 did not reach Skyline at all, which the map correctly shows: the missing part of the trail was the most severe. The Southesk Lake Loop trail disappears between 1938 and 1985, but in the 1970s Parks Canada had designated this a “special area” and restricted entry.

Trails now known for being tough slogs not long later were in wonderful shape back then. The North Boundary Trail, today a wildland, was in the 1970s considered one of the best-maintained backpacking trails in western Canada. Maligne Pass was still wet for early summer hikers, but generally safe, and the worst ford over the Maligne River was bridged. Even Mystery Lake, to be quoted later as one of the great why-bother trails of the Canadian Rockies, in the guides of the ’70s sounds like merely an interesting and difficult late-season hike.

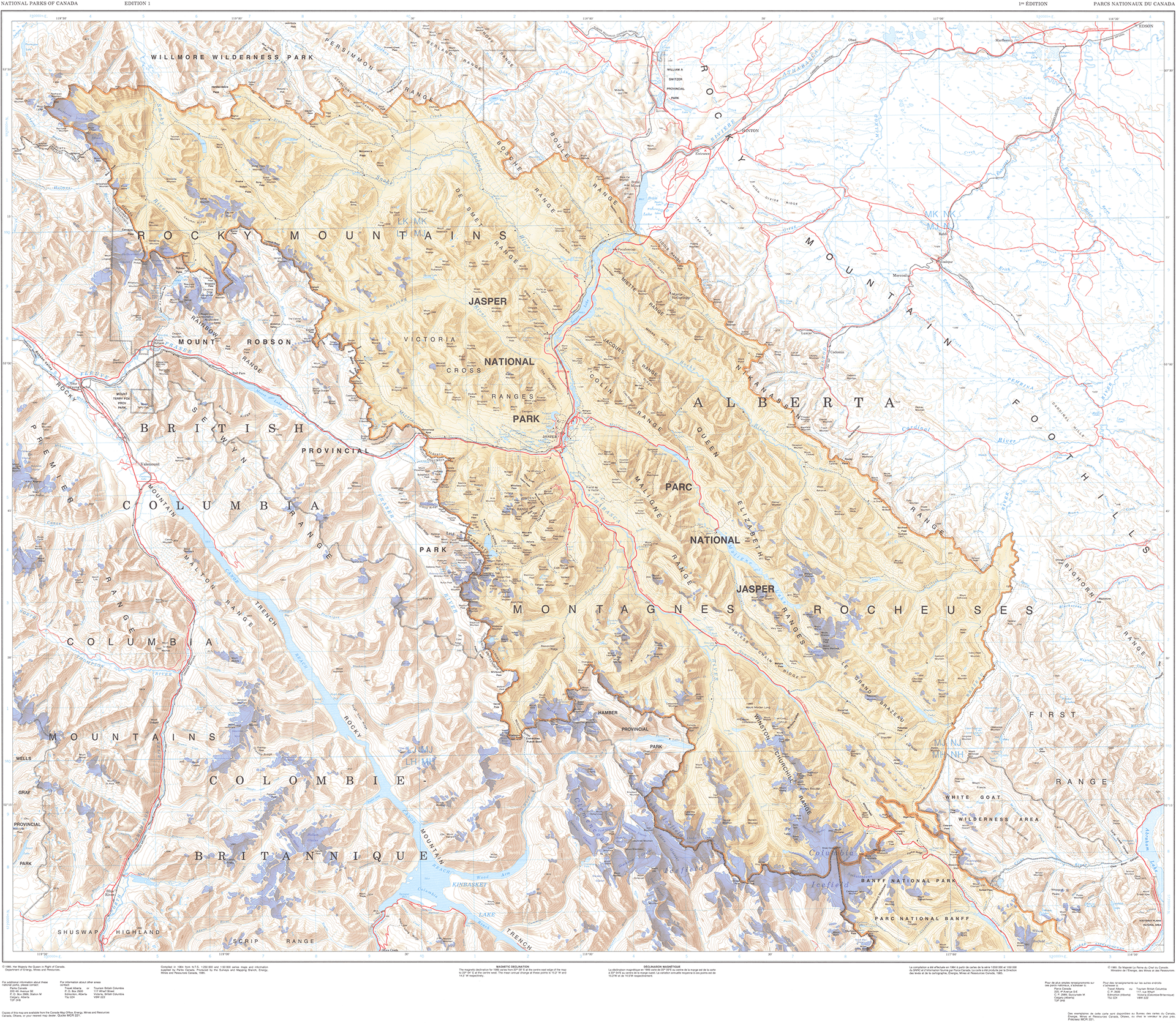

The Jasper map from eleven years later is so detailed, so thorough, and so rich that I had to do a double-take and make sure that yes, this was intended for the general, backcountry-using public.

This map probably represents Jasper National Park’s public trail system as generously as it could ever have been: the maximum number of trails shown at the time of their greatest extent. It is also, in the strange way these things have of working out, by far the best looking. The official 1984 brochure contains an impressionistic not-for-navigation map which omits much; the 1985 map has almost everything. Some are on this map and few other places, including such duds as Vine Creek (“of slight scenic interest”—Don Beers, Jasper-Robson: A Taste of Heaven), Mystery Lake (“a long, rough day trip from Miette Hot Springs, and not much fun as a backpack either”—Brian Patton and Bart Robinson, Canadian Rockies Trail Guide ninth edition), and Short River (“I can’t really figure out what the hell this is”—Marc of the Trail, North Boundary Trail day 8 video), useful for parks staff or privacy-obsessed equestrians but few others.

Some trails now infamous, such as the Jacques Pass–Merlin Pass trail from the Yellowhead to Jacques Lake, were once a bit better. The park’s 1985 trail info guide calls the trail “wooded” but “highlighted by two mountain passes,” which doesn’t sound too bad; hardly a decade later, Don Beers called the faint, overgrown trail “one of the very few mountain destinations I take satisfaction in knowing I will never have to go to again” with his main complaints being brush, difficult routefinding, beaver dams, and soggy trail9.

Though it’s tempting to assume otherwise, this was a map for the general public. I am aware of at least one staff-focused trail that existed then but is not on the map10. Probably, in the 1980s, Jasper’s backcountry really was overbuilt. As today, being on the map didn’t mean it was maintained, and contemporary trail guides are replete with references to dangerous fords and long, rough bushwhacks even then. Backcountry use steadily declined from the late 1970s until 2012, as the last generations used to riding horses through the woods aged out but the backpacking boom hadn’t yet hit. It wasn’t until surprisingly recently that it was simple for ordinary, not-conspicuously-fit people to carry ten days’ worth of food and gear on their own backs. Since the national parks have never allowed motorized travel in the backcountry by the general public, there was a long decline before lighter gear started to allow horse-riding distances on foot11.

“Overbuilt” is a very relative statement. According to former Jasper trail boss Jim Suttill in a 2016 interview with the Jasper Fitzhugh, that “overbuilding” cost about $500,000 a year to maintain in the 1980s. This would be about $2 million in today’s money, against a 2023–24 operating budget of $25.5 million12. Officially, only about 1% of park visitors access the backcountry, but since demand for good trails exceeds supply, this is only so revealing. There was $24.6 million that year for a caribou breeding program that will be accessed by zero park visitors, and $46.4 million for various frontcountry improvements. The caribou program is ironic, since a 2010 strategic review identified caribou habitat as an excuse that could be used to hide massive backcountry budget cuts13. It would cost much more than $2 million a year to bring trails back from the dead, and with wildfire recovery it’s hard to justify in the short term, but their death was a conscious choice.

From this point on, the story is abandonment. The question of what it means when Jasper National Park abandons a trail is such a complicated one that I’ll address it fully in part two. In Jasper, abandonment never means “permanent closure.”

As in the case of the caribou, Jasper National Park can always take refuge in the fact that, by law, Parks Canada’s first priority must be respecting the nature and history of their parks. Like many laws this is more a nice feeling than anything you should take too literally which is why there are, for example, great big mainline railways and truck-filled highways running through Jasper and Banff, and both parks encourage packed tour buses with thousands of people buying future-landfill crap made in Asia. But it’s a nice shield to hide behind when a park can no longer be bothered to keep up an amenity.

To some degree, abandonment stems from a change in standards. Fortress Lake is one of the infamous inaccessible trails in Jasper, with no bridge over the Athabasca River since 2014; Parks Canada now refers to this as the 14.6km “Chaba Trail,” ending at Athabasca Crossing campground. A bridge across the Athabasca was only installed in 1985. Before that Parks Canada said “fording on foot is difficult and not recommended until late August when the river level has dropped;” trail guides referred to the Athabasca River as maybe the worst ford in the Rockies, but it was still an option. In 2025, Parks Canada says that “travel beyond the Athabasca Crossing campsite is not possible due to an unbridged crossing of the Athabasca River.” The trail is still hiked by packrafters and the very brave. It’s probably in no worse shape than it was in the 1980s, but fashions have changed. Backcountry users expect to be safer now than they did 40 years ago, and to require fewer skills.

An abandoned trail is no longer advertised. Guidebook makers and map companies who work with Parks Canada usually remove them. You can still go, but you need to call the parks office for a random camping permit, and quotas can be tight. Because of this, naturally, fewer people do them, and as first-person experience fades good information becomes hard to find, which means even fewer people do them. The list of people who will tackle an abandoned trail without an up-to-date map and without a GPS route, counting on picking out the overgrown track or following decades-old blazes, will never be large. To the ordinary, one-week-a-year backpacker, unless he pays a guide to bring him up the route, it may as well not exist.

So we move into the twenty-first century. The sharper contrast on the current, 2019 map makes the trails stand out more than they did in 1985. It’s easy to sharpen contrast when you have so much less to show.

(Get the 2012 map here, from the Parks Canada History Archive; it’s not uninteresting but similar to 2019 and a man must have limits.)

This, the official, current map as of this writing, is inaccurate. It is missing most of the Maligne Pass trail, and it shows the old backcountry cabins in the Tonquin Valley which, in an anti-human act, Jasper ordered shut down in 2022. Tonquin Valley is shown as a horses-permitted route, which it no longer is. All the same, the many vivid red warnings once you get off the beaten path promise that the situation is even worse than the lines on the map make it look.

Some changes are understandable. The South Boundary Trail once started at Jacques Lake, following the Rocky River to Rocky Forks, but it burned in 2011. The trail has been obliterated, with thousands of trees down over 20 kilometres. It was never really the South Boundary’s scenic highlight anyway, the best is still accessible over Rocky Pass, which is a pain to reach but reasonable doable. If one was to bring the trails back, that would have some of the most effort for some of the least reward. There’s no rule that says every trail has to be as good as it was in 1938, nor should there be. The Jasper section of Cataract Pass, way up in the subalpine, is breathtaking but a rocky, watery expanse that was always more route than trail. It’s probably no worse hiking unmaintained than it would be otherwise.

But some trails are missed. Elysium Pass is convenient to the town of Jasper and, at 30.2 kilometres return with heavy climb, a good three-day hike, one up, one enjoying the scenery, and one back. In 1994, Don Beers described it as a “beautiful area to explore” with many splendid views. It was a favourite of mountaineer Frank Smythe, who was assigned to the area during the Second World War and knew what he was talking about: he pioneered two routes up Mont Blanc, was the one-time holder of the highest mountain ever climbed, discovered many beautiful parts of the Himalayas, and in 1938 was one of four Britons to reach the highest point yet on Mount Everest. Today, Ben Nearingburg’s Starry Summit Mountain Adventures guides the trip but the area deserves more love.

Then there’s the Southesk Lake Loop. I met two separate people doing it in 2022, which under the circumstances is a crowd since that trail is supposedly a nightmare and the access, off the Grave Flats Road over Rocky Pass, is annoying14. It is sometimes guided. People like loops, mountains, and lakes, and I know people keep their eyes on that trail: sometimes they comment on my blog. In September 2023, a party attempted the Southesk Lake Loop and needed helicopter evacuation when storms made the Rocky River impassible. They were smart to call for help, but a helicopter carrying a hiking party three-quarters of a mile through the backcountry to cross the river and warm up is a reminder that “no bridge” is not actually a zero-cost solution.

As the easy trails fill up, not just in Jasper but all over the Canadian Rockies, people do the hard ones. Some of those people will be unprepared and some will be unlucky. People will go on Reddit or YouTube to hear of hikes “off the beaten path,” and the helicopters will go in after them. Or they won’t, they’ll sit in the cities and rot, and worse things will happen. The time has come to open the backcountry up again.

Appendix

This is non-essential reading and you will miss nothing if you close the tab, but as Bill James once said, “the creation of data is a holy act; not really, but occasionally I need to feed my own caricatures.” Having put all this information together, I feel the need to spit it out.

I analyzed six years from Jasper National Park trail history: 1938, 1974, 1985, 2012, 2019, and 2025. For the first five, I used official full-park maps available at the sources linked above to estimate the breadth of the Jasper trail network, as well as Parks Canada’s official written trail guides from the 1930s and 1980s to make sure nothing obvious was missed. For 2025, the map is out-of-date so I used the Parks Canada online trail descriptions to fill in changes. 2025, therefore, has a mileage bias upward because it’s #currentyear; very probably I could have added a side-trail or two in 2012 or 2019 if I had access to the data that show them, but I don’t so I didn’t.

I also included only “backcountry-relevant” trails, which means a trail that, from my chair in 2025, you would be hardly likely to embark upon without a tent. This is entirely a matter of opinion. Of course one can day-hike Celestine Lake, or Rocky Pass, and some do. Some run Skyline in a single day. These trails are nevertheless counted, because most don’t. I made a definition and stuck to it. In 1938, the Valley of the Five Lakes was the best access to what-there-was-of-Skyline and a good way to Maligne Lakes, without really convenient access from the brand new Icefields Parkway. It was certainly backcountry-relevant then, but it is not now, and it is not counted in these lists. When finding a historical trend, crediting the 1930s with extra trail because you had to ride your horse further to get anywhere than you did in 2025 would be missing the point, and pinpointing the precise moment when, say, the Valley of the Five Lakes stopped counting is a job for the Holy Spirit, not me. On the other hand, the fact that the Yellowhead Highway did not go west of Jasper and there was a horse trail to Moose Lake where today there is a highway is counted, because that was a clear-cut backcountry experience that is no longer available.

My statistical goal was to capture a trend, not to concentrate on accurate trail lengths. Trail distances in the national parks have been, historically, inaccurate. They were estimated based off how far a warden riding on horseback figured it ought to be. Starting in the 1970s, the Canadian Rockies Trail Guide measured trails with a wheel, obtaining more accurate distances, and of course in the twenty-first century GPS mapping has become ubiquitous. This means that it can be difficult to judge if a trail in 1938 was billed as different than the same trail in 2025 because it was different, or because it was measured more accurately, or, more probably, some combination of both. Therefore, except in flagrant and measurable cases, such as when a road was closed or opened, or a part of the trail was actually missing one year, I made no attempt to keep up a running history of trail lengths. I picked a source and stuck to it; the South Boundary Trail from the Rocky Pass Junction to the Brazeau Loop was 79.3 kilometres in 1938 and 79.3 kilometres in 2025. It hasn’t really not moved at all, and 79.3 km isn’t the right distance even if it hadn’t, but to build a trend it’ll do, saving a huge amount of work that would only give the impression of false precision rather than the real thing. Sources were, in order of priority: the official Parks Canada figures, old trail guides, Google Maps for parts of trail that are now roads, AllTrails once (on the Southesk Loop), and a few distances for long-forgotten trails eyeballed off the map.

Finally, I adopted an arbitrary and inconsistent approach when trails left Jasper National Park. For trails where the outside-the-park portion was integral to reaching a common trailhead, I included it. This affects primarily the North Boundary Trail (down the Berg Lake Trail in Mount Robson Provincial Park), the South Boundary (a long-established hook route into provincial forest lands near the Southesk River, and the Nigel Pass conclusion in Banff National Park), the Moosehorn Creek trail (a day or two’s hiking through Alberta provincial parks with Jasper on either side), and the Fiddle River trail (starting at Miette Hot Springs and ending in Whitehorse Creek Provincial Park). For trails where the outside-the-park portion was just a place you could go, I did not count them. This includes Moose River, also in Mount Robson Provincial Park, an optional exit from the North Boundary Trail that has always been less popular and often used as a loop with the Berg Lake, as well as all those trails where you watch the dotted line go to the edge of the map and stop. Non-national park trails do not fall so clearly into “official” and “not official” as Jasper’s do.

With those caveats in mind, if the trail was not on the map, I did not include it. If it was, I did. This mostly affects that weird 1974 map in ways that will be seen when I list them. It also means that trails which were not mapped for the general public in these sources but were nonetheless there, such as the Sawtooth cabin trail, the Six Pass route near Maligne Pass, and probably dozens of climbers’ routes, are never shown.

Sources for trail details beyond Parks Canada’s information were the Canadian Rockies Trail Guide by Brian Patton and Bart Robinson, second (1978), fourth (1990), and ninth (2011, reprinted in 2017) editions, and Jasper–Robson: A Taste of Heaven by Don Beers, 1996.

The use of the metric system is a courtesy to anyone trying to research further, since the original sources are all metric, and is not an endorsement. You may also download the spreadsheet used to sort all this information.

Changes between 1938 and 1974

-

North Boundary Trail from Celestine to Mount Robson shortened by 18.8km (opening of the Celestine Lake Road to the trail junction of Celestine Lake).

-

North Boundary Trail from Rock Lake to Willow Creek lengthened by 8.4km (opening of the Rock Lake Trail to what had previously been the intersection with the Moosehorn Creek trail).

-

North Boundary Trail side trip to Rock Creek–Eagles Nest Pass added at 16.5km.

-

Moosehorn Creek trail lengthened by 8km (alternate route through Grindstone Pass).

-

North Boundary Trail alternate from the area of Oatmeal Camp to the Moose River via Campion Creek deleted, removing 9km.

-

South Boundary Trail from Mountain Park to the Rocky Pass junction over Rocky Pass added at 18.7km.

-

Southesk Lake Loop western branch from Southesk Lake to the Rocky River deleted, removing 39km (re-added in 1985; Parks Canada restricted access to this trail in the 1970s).

-

South Boundary Trail side trip to Dowling Ford added at 3.8km.

-

Fiddle River trail added at 33.7km; incomplete, as there is a gap between Fiddle Pass and upper Whitehorse Creek.

-

Saturday Night Lake Loop lengthened by 15.1km as the loop is completed from Minnow Lake to today’s route.

-

Skyline Trail lengthened by 23.8km as the trail crosses the Notch to today’s route.

-

Wabasso Trail lengthened by 4.2km to today’s route.

-

Watchtower Trail added at 9.8km, stopping at today’s Watchtower campground (which, despite all the probable mistakes on this map, was accurate).

-

Maligne River/Medicine Lake trail deleted, removing 37.6km; today’s Maligne Road.

-

Tonquin Valley Loop shortened by 24km as the Edith Cavell and Marmot Roads shorten the route.

-

Meadow Creek trail to the Tonquin Valley deleted, removing 14.3km, though this trail was still used by the Alpine Club of Canada as late as 1977.

-

Moat Lake and Tonquin Pass trail deleted, removing 6.8km (re-added in 1985). Decent chance this is a map mistake, at least as far as Moat Lake.

-

Athabasca Pass trail shortened by 37.9km, as the trail peters out early near Tie Camp (re-lengthened in 1985). In my opinion, this is likely a mistake on the map.

-

Geraldine Lakes trail deleted, removing 7.8km (re-added in 1985, shortened to account for the Geraldine Road). In my opinion, this is likely a mistake on the map.

-

Fryatt Valley trail shortened by 2km (replaced by the Geraldine Road).

-

Wynd–Moose Lake trail deleted, removing 53.1km (replaced by the Yellowhead Highway).

Changes between 1974 and 1985

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to Little Heaven–Spruce Tree lengthened by the addition of a Desolation Pass option, adding 6.5km.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail up Lower Mowitch Creek added at 8km.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail through McLaren’s Pass added at 18.4km between Little Heaven and Blue Creek.

-

Moosehorn Creek trail shortened by 8km as the Grindstone Pass alternate disappears again.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail from Blue Creek to an unnamed lake near Mt. Simla added at 15km. I have found nothing besides that line on the map to suggest this trail ever existed. Probably a patrol trail; the ford of the Snake Indian River would have put this outside the tourist’s run.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to Bess Pass added at 6.7km.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to Short River added at 15km. Another probable patrol trail; a branch already disused by 1978 headed east to Azure Lake, neatly bracketing the most navigable part of Jasper’s northern border.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to Coleman Glacier added at 8.9km.

-

Jacques Pass–Jacques Creek–Merlin Pass trail added at 27.7km from the trailhead to the junction of the Jacques Lake trail.

-

South Boundary Trail Rocky Pass entrance shortened by 7.3km, replaced by the Grave Flats Road.

-

Southesk Lake Loop western branch from Southesk Lake to the Rocky River re-added at 39km.

-

Cataract Pass spur off the Nigel Pass trail added at 6km.

-

Fiddle River trail lengthened by 4.1km as the gap is closed.

-

Tonquin Valley side trail to the Eremite Valley and Arrowhead Lake added at 17.6km.

-

Moat Lake and Tonquin Valley trail re-added at 6.8km.

-

Tonquin Valley side trail to Verdant Pass added at 7.3km. Unmaintained by the 1990s.

-

Athabasca Pass trail re-lengthened by 37.9km. The maps are not clear whether it ends at Athabasca Pass campground or the pass itself. The current trail officially ends at the campground. However, nobody has ever hiked to Athabasca Pass campground and not seen Athabasca Pass, so the 800 metres or so this involves is part of the statistics from here on out.

-

Geraldine Lakes trail re-added, adding 6.2km (shorter by 1.6km than 1938 because of the Geraldine Road).

-

Miette River trail added at 43.5km from the trailhead to the junction with the Moose River trail. Unmaintained by the 1990s.

-

Mystery Lake trail added at 10.1km.

-

Elysium Pass trail added at 15.1km. Of the 1985-only trails in the centre of the park, this is the only one reviewed positively in the trail guides.

-

Vine Creek trail added at 8.2km. Unmaintained by the 1990s, and probably never much-loved.

Changes between 1985 and 2012

-

North Boundary Trail from Celestine to Mount Robson lengthened by 5.2km, as the bridge over the Snake Indian River is closed to vehicles.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to Rock Creek–Eagle’s Nest Pass deleted, removing 16.5km.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to Little Heaven–Spruce Tree shortened by 17.5km, as Glacier and Desolation passes are deleted and the trail ends at Spruce Tree campground.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail up Lower Mowitch Creek deleted, removing 8km.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail through McLaren’s Pass deleted, removing 18.4km.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to Hardscrabble Pass shortened by 13.9km as the trail ends at Natural Arch campground.

-

Moosehorn Creek trail deleted, removing 58.4km.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to that weird lake near Mt. Simla deleted, removing 15km.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to Bess Pass deleted, removing 6.7km.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to Short River deleted, removing 15km.

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to Moose Pass deleted, removing 9.5km.

-

Jacques Pass–Jacques Creek–Merlin Pass trail deleted, removing 27.7km.

-

South Boundary Trail from Jacques Lake to Rocky Forks shortened by 22.8km, as the trail starts at Grizzly campground to Rocky Forks.

-

Southesk Lake trail from the South Boundary Trail near Isaac Creek deleted, removing 22km.

-

Southesk Lake Loop western branch from Southesk Lake to the Rocky River deleted for the last time, removing 39km.

-

Cataract Pass deleted, removing 6km.

-

Watchtower Trail lengthened by 3.4km as it links to the Skyline Trail.

-

Maligne Pass trail deleted, removing 47.7km. It will return, first in part in 2019 then wholly in 2025.

-

Tonquin Valley side trail to the Eremite Valley and Arrowhead Lake shortened by 4.2km, as the trail stops short of Arrowhead Lake.

-

Moat Lake and Tonquin Valley trail deleted again, removing 6.8km. The first 2.8km, to Tonquin Valley Lodge, was certainly maintained and in regular use at this time.

-

Side trail out of Maccarib Campground in the Tonquin Valley added at 2km.

-

Tonquin Valley side trail to Verdant Pass deleted, removing 7.3km.

-

Miette River trail deleted, removing 43.5km.

-

Mystery Lake trail deleted, removing 10.1km.

-

Elysium Pass trail deleted, removing 15.1km.

-

Vine Creek trail deleted, removing 8.2km.

Changes between 2012 and 2019

-

North Boundary Trail side trail to Coleman Glacier deleted, removing 8.9km.

-

South Boundary Trail from Grizzly campground to Rocky Forks deleted, removing 12.9km, leaving only the 9.1km from the Rocky Pass Junction to Rocky Forks campground of the original 44.8km South Boundary Trail western entrance.

-

South Boundary Trail side trail to Dowling Ford deleted, removing 3.8km.

-

Maligne Pass trail partially re-added to Avalanche campground, adding 14.7km. Avalanche campground was (and is) available to only one party per night, meaning this remained a seldom-used route.

-

Fortress Lake trail shortened by 9.4km and rebranded the “Chaba Trail” due to a bridge failing at the Athabasca River.

Changes between 2019 and 2025

-

Maligne Pass trail fully re-added from the Poboktan Creek trail to Maligne Lake, adding 33km.

-

Tonquin Valley side trail to the Eremite Valley re-lengthened to Arrowhead Lake, adding 4.2km.

-

Moat Lake and Tonquin Valley side trail re-added as far as Moat Lake, adding 4.7km.

If you’re reading this, you are officially a trail nerd and should have a cookie.

- Because of the wildfire, 2024 hardly counts.

- In compiling this I tried to make the length of each trail “consistent with each other,” not “perfectly accurate.” Trail reroutes are not accounted for at all except in flagrant cases, such as what was once a trail becoming a road. These numbers should give an accurate trend but are by no means accurate statistics. For grizzly details, see the appendix.

- A few miles of side trail in the Tonquin Valley are also advertised again; this is reflected in the statistics but I am almost sure does not reflect any real change.

- By “days” I mean ordinary hiker days, for people with big packs and casual gear who don’t do it much. Most do Skyline in three or four, though many including the author do it in two. It’s distinct from something like the Geraldine Lakes or the Saturday Night Loop, where the only way to spend three days is if you deliberately go slow.

- If not for the wildfires, this bridge would have been replaced in the fall of 2024. As it is, it’s expected to happen in 2025 sometime.

- The Moose River trail appears for the first time in 1964, which is probably more than coincidental, but a bit hard to figure.

- Which are nowhere near each other, and that two similarly-named trails have such similarly-named trailheads has surely messed up one would-be hiker in the past fifty years.

- It hasn’t got the Four Point warden cabin but who cares?

- The area around Jacques Lake is infamous for how often trail needs to be rerouted to account for the water table, and the beavers’ idea of fun.

- The trail between the South Boundary Trail and Sawtooth warden cabin; Sawtooth cabin is on the map so the trail was there.

- Even today, Parks Canada uses either helicopters or horses in the backcountry, and very seldom quads. Horse trails are too narrow for quads, and since the public isn’t able to ride up and widen them, they stay that way.

- Parks Canada says the wildfire so disrupted things they weren’t even sure what their 2024–25 operating budget was. There are times to throw money around first and account for it later, and this was not a bad one.

- Thanks to the Canadian Backcountry Trails Preservation Society for obtaining this, and other interesting documents, by freedom of information requests. The CBTPS’s document archive is no longer online; this document is mirrored by permission.

- I met one other party doing the South Boundary Trail that trip, and I was on the South Boundary Trail.

Hello Ben,

Great article about the backcountry trails in Jasper, although I would add that it is a Parks Canada issue not just Jasper. All of the Rocky Mountain parks are losing trails. The biggest factor contributing to their decline, from my point of view, is the lack of equestrian usage. Take for example an area like the Willmore Wilderness north of Jasper, a wilderness park with an operating budget a fraction of what Jasper has yet the trails in the park are in great condition, why? because of equestrian usage. The same applies to the Bighorn backcountry. Wherever there are horses there are good trails. Of course there are drawbacks to horses in the backcountry but in terms of trails, they maintain themselves.

Also, you stated “An abandoned trail is no longer advertised. Guidebook makers and map companies who work with Parks Canada usually remove them.” That is definitely a true statement and one of the reasons I started my own mapping company a few years ago. I’ve stayed away from the National Parks for now and focused more on the parks surrounding them but one thing that I never do is omit trails, if it exists and I’ve hiked it, it gets published. I like to think of it as half recreational map, half archival document.

Nonetheless, thanks again for the great article and know that I do have plans to publish a map for northern Jasper, which will shows all the trails and who knows, maybe it will help revitalize some the backcountry in Jasper.

Great research and summary, plus useful for those of us poking around and trying to figure out the condition of a former/current/maybe/sometime trail before attempting it with horses 🙂 I’m hopeful at Sean Elliot as the new barn boss in JNP will convince the higher-ups to let’er rip with horses and trail clearing. Can always hope!