This August I’m off hiking in Jasper and Banff National Parks. Take the train in to Jasper, camp for a night in the frontcountry, hike a trail, take the bus to Banff, another frontcountry night, more hiking, camp at Lake Louise, then head home. Since I am the sort of person who enjoys planning trips almost as much as going on them, I had this planned out, with routes researched, campgrounds picked, and schedules ready, before Christmas.

Good thing. I needed a night in a frontcountry campsite in Jasper; reservations opened up January 7. The largest campground in the park is under renovation for all of 2020 so I played it safe, got up early to snag my spot. This was smart. Parks Canada’s database server failed under the strain of us early-risers; as errors and “processing…” queues kept me waiting I could watch the sites I wanted turn from green to red. Luck was on my side: I got in. But that was merely the first battle in a long war, a campaign of all against all between thousands of fellow-travelers from Canada and around the world, for the right to go camping.

The worst part is, there isn’t a better way.

The next morning was Banff frontcountry opening day, and I needed two sites. Think with sympathy of the systems administrators who find themselves getting DDoSed because the bosses decided how to manage their business without asking, and of the social media interns and customer service agents who are shouted at by the public for the inevitable faults of technology. The Parks Canada website was essentially unusable for hours. Every step of selecting a campsite was a lottery where you’d see if the database server would let this particular query through, and if it didn’t you could only try again. Many users, including me, had our credit cards charged but, because the reservation database was inaccessible, didn’t actually get campground reservations1. I spent so much time trying to book my sites that I was late for work but after three and a half hours either enough people gave up or the sysadmins were able to lay on enough extra power that I was able to check out, campsites in hand, just in time. As of this writing the 64-site Two Jack Lakeside campground is entirely sold out most summer weekends.

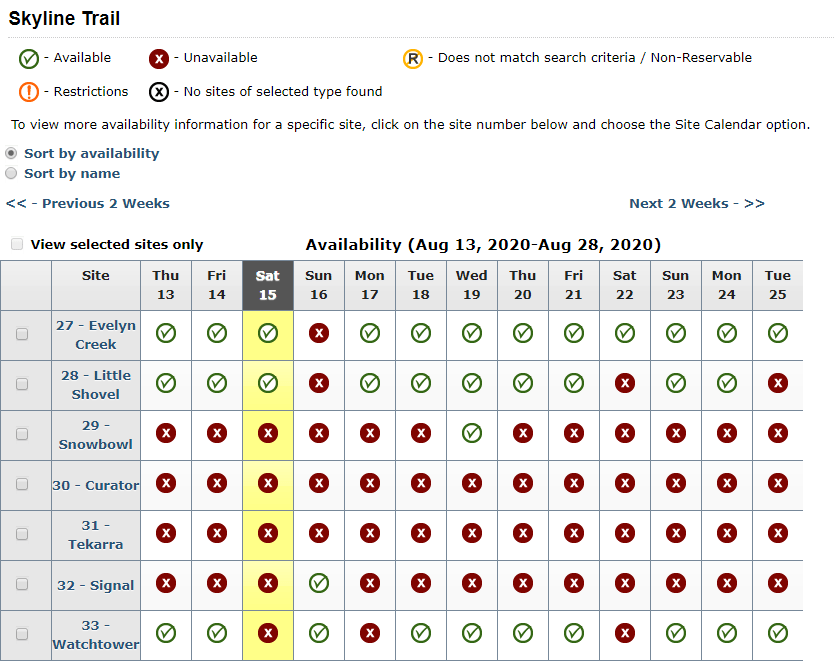

That was an end to the stress for two weeks, but starting January 22 backcountry reservations opened. A backcountry campground is less popular but it has a fraction of the sites and, unless you want to hike 25 miles on day one and five on day two, it’s important to get just the sites you want. Boy was I on the ball for Jasper: I’m hiking Skyline, one of the most popular trails in the park, and took no chances, rolling into the office early so I could be sitting with my finger on the mouse button the minute reservations were available. Reservations opened at 7:00, I had my confirmation at 7:02, and by 9:00 the four most desirable campgrounds on Skyline2 were booked nearly solid from July 4 until mid-September. For those in more obscure niches it was worse: the canoeing sites on Maligne Lake and the Athabasca River were just gone, all-but-sold out for 2020, as was the much-coveted single spot at the decommissioned Maligne Pass’s Avalanche campground. If my train had broken down on the way to work I’d have needed to cancel my vacation. It did break down on my way to booking a campsite in Banff the next morning, but luckily this was a lower-demand site and didn’t sell out within an hour. Lucky me.

So far, touch wood, planning my morning around being online with credit card in hand at the soonest possible instant has worked. But I’m deeply blessed. I can plan my vacations well in advance, I have no kids yet, I don’t own my business or have the sorts of responsibilities where I need to hold out and see when I can get away. If I lived a slightly less fortunate life, if I didn’t know in January whether little Brédolyn’s baseball team would be in the playoffs or whether work would let me out that week, I just flat-out would not be able to camp in these spots.

Things still aren’t certain. Canada’s park access is not only limited but the rules vary from park to park. My route in Banff goes through British Columbia’s Mount Assiniboine Provincial Park, and BC has its own reservation system which allows you to reserve sites four months in advance. This is a smarter way to manage demand on your poor servers than what Parks Canada does, but it leaves me one thing left to worry about, one more early wake-up in the spring to put a bow on my hiking plans.

I’ve made the point before that access to the wilderness, like everything else in a society with scarcity, is rationed whether you admit it or not. At present Canadian national parks ration access based on how low-time-preference you are and how on-the-ball you, or the guy who makes reservations for you, is. If your life is too fluid to book an August hike in January then either go someplace less popular or be very lucky: there are always last-minute cancellations in these parks because the current system encourages you to book up every site you want at the earliest possible moment even if you just might use it. There’s an unspoken assumption that doing it this way is fairest.

It’s instinctively unfair to ration by price; it sounds like an affront to the very idea of a national park, which should be accessible for the entire nation, though as we’ve established that’s not actually an option. Weirdly, our parks have the worst of both worlds. Save the West Coast Trail they don’t post high prices, but they do tack on hidden fees which exploit without deterring. A stiff ($11.50) reservation fee might make sense, if only because of those who book-then-refund-later, but although I got my Banff campsites at the same time, on the same website, with the same credit card, they were at separate campgrounds so incurred separate reservation fees. One campground added a mandatory $8.80 fire permit I didn’t want. And of course this is just the cost of camping; there’s a separate admission fee when you get to the park, and every business, every guide, every photographer, every bus driver that you deal with in the park is licensed by Parks Canada and quietly passes the cost on to you. Meanwhile, Jasper has been decommissioning trails, admission for new Canadian citizens is free, and the government promised thousands of dollars for “lower-income families” to go camping, so problems for the rest of us only get worse.

Other jurisdictions take different approaches. I contemplated hiking a portion of the Continental Divide Trail from Montana into Alberta but the American Glacier National Park backcountry reservation system stopped me. Their 2020 reservation season opens March 15: all reservations submitted on opening day are processed in a random order and you’ll be informed whether you have a reservation or not in up to eight weeks. Fees are high: US$10 just to get your foot in the door, plus US$30 if you win a reservation, plus US$7 a night. Glacier National Park, in short, rations their advance-reservation campsites based on luck.

Yet the Americans also offer comfort to the flexible, last-minute traveler: I gave up on them since I couldn’t face the thought of finding out in May whether I had a vacation or not, but unlike the Canadian Rocky Mountain parks, the Americans offer a healthy walk-up inventory if you want to show up in Montana on the day and take your chances. The walk-in camper is not charged the US$40 application and reservation fees, just the US$7 a night. This incentivizes people from the region, who are dedicated to visiting their natural heritage and flexible enough to work around conditions, and discourages international travelers like me, who need plans set in stone but may as well go to Glacier as anyplace else. Which, for a national park, is a perfectly reasonable thing to do.

There’s always room in the outdoors if you go far enough. Jasper’s North Boundary Trail, for example, has availability at virtually any campsite on virtually any day3. As it happens I do want to hike the North Boundary, but I’d need two weeks, reasonably formidable backcountry skills, and a way to get back to civilization from Mount Robson Provincial Park, over 100 kilometres away by road from the trail’s starting point with zero public transportation4. Less popular trails may be spectacular and rewarding, but they’re less popular for very good reasons.

What do you do about this? “Build more facilities,” “set aside more parks,” this is good as far as it goes, but there are limits. The Rocky Mountains are essentially park from the international border to the Yukon. Build trails, but the closures in Jasper in the past decade were driven by conservation concerns and those don’t go away. If you want people to visit new ground you need to get people to it, so build highways and railways in a country where land claims and environmental paralysis keep us from running 36-inch-wide oil pipelines. Easy.

Pick the low-hanging fruit when you can; stop the stupid subsidies, run a few more buses and trains, open up trailheads that are accessible only to the very high-agency today. Provincial parks are prone to rotting on the vine: Sooke Mountain Provincial Park, near Victoria, recently banned backcountry camping because they have neither the time nor the resources to safely develop it. But sit down, start looking, and there are fewer cheap wins than you might think. Meanwhile interest in outdoor pursuits is growing, everyone wants nature shots on their Instagrams or content for their shitty blogs, Mountain Equipment Co-op is somehow losing money but that aside the problem’s not going away. So you ration. You gotta.

And when I get up at dawn again and F5-gang the BC Parks website so I can get the last campsites I need I’ll be frustrated, but happier than entering a lottery, or paying auction prices, or showing up in Banff on vacation day saying “so, am I going camping or am I hanging out at A&W all week?” Whenever demand exceeds supply, which is most of the time for most things, you pay for it somehow.

- I should say that my extra charges were reversed punctually without me even having to complain.

- Snowbowl, Curator, Tekarra, and Signal.

- Though I’d be in tough on the far end, when I’d need to descend Mount Robson Provincial Park’s Berg Lake Trail in a day as the campsites have been booked solid since December.

- The nearest public transit is in the town of Valemount, a 39-kilometre highway walk from Mount Robson, where you can bus to Prince George twice a week or stand on an exposed rail siding waiting for the train to Vancouver or Edmonton three times a week and court hypothermia.

One reply on "Park Reservations Unfixably Suck"