The South Boundary Trail. To some those words are instantly evocative. They mean history, grandeur, self-reliance, and solitude.

Jasper National Park has beautiful backcountry, from Skyline to the Brazeau to the Tonquin Valley; the South Boundary’s isn’t the same. The scenic highlight is Nigel Pass, which is also a day hike and easily backpacked on the Brazeau. Otherwise, there are wonderful moments but not constant stimulation. No 3,000-foot climbs, no camps above treeline.

The South Boundary just feels different. The ninth Earl of Southesk put it on the map in 1859 when, recovering from injury, illness, and the loss of his wife, the 32-year-old peer explored the Front Ranges, defined a great Rocky Mountain backcountry trek, met legends of the Canadian West, read Shakespeare and Bulwer-Lytton, and wrote his account with a personality that any fan of obscure backcountry content will recognize. The hunters with him had hardly the vaguest idea where to go: they were experts, not guides, and the earl pioneered this route.

As Jasper matured the South Boundary became popular until, around 1994, the parks began their long retreat from the backcountry. Wildfires in 2003 and 2006, and a flood in 2013, decimated the trail, and little was repaired. Reports discussed how difficult the path could be to find, let alone hike.

Then, in 2019 Stuart and Evelyn Howe recorded a two-and-a-half hour video of their hike. They found Rocky Pass, navigated the washouts, made it to the old paths above the Southesk burn, then got down to the bridge. They showed what victory looked like, posted their GPS tracks, and more would-be hikers were inspired to follow them. In the years since the trail’s been better-marked by cairns, markers, and flagging, and the park has made a couple maintenance trips. One hesitates to call a 75-mile trail with chancy fords, multi-mile route-finding, primitive campsites, unbrushed trails with six-foot willows, and one thoroughly remote trailhead “easy.” But it mostly is.

Formerly, the South Boundary Trail ran from Jacques Lake, off the Maligne Lake Road, up and over the Rocky River, along the Medicine Tent, over Cairn Pass, then near the banks of the Cairn and Southesk Rivers until finally turning south and following the Brazeau River out of the park.

The 2003 wildfire obliterated the stretch between Jacques Lake and the former river crossing at Rocky Forks. The bridge and trail were both destroyed; those few gutsy enough to have fought through the hundreds of downed trees and near-total obliteration of the track and reach the Rocky River found that it is an impossible ford on foot even in September. As a result, the northwest trailhead for the South Boundary is now, both officially and as a matter of convention, at the Rocky Pass trailhead parking lot, adjacent to the boundary of Alberta’s Whitehorse Wildland Provincial Park, out in the end of nowhere south of Cadomin on the Grave Flats Road.

When Lord Southesk rode it, the area was even wilder than it is today, but he could hunt for his food and the Hudson’s Bay Company, owners of the territory up to the continental divide until 1870, was on his side. At a time when the HBC swore Rupert’s Land was unfit for settlement the earl got five-star treatment, traveling from Lachine1 to Fort Garry2 with Sir George Simpson and John Rae. There he met Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché, followed the Carlton Trail west to Fort Edmonton, shot bison, ate saskatoons, and spoke with Joseph Brazeau, the great character and linguist of the West after whom other explorers named the Grand Brazeau glaciers and the lakes and rivers that flowed from them. Traveling on horseback with expert hunters, he had intended to follow the Athabasca to the HBC post at Jasper’s House3 but, hearing there was no game, the earl stopped at Lac Ste. Anne, met future St. Albert city founders Father Albert Lacombe and Andre Cardinal, wrote his opinions on literature and railroads, then followed the Athabasca and McLeod Rivers south into the foothills of the Front Ranges and approached Rocky Pass4.

Traveling with Simpson and horse-trading with Lacombe would have been a good summer already but Lord Southesk, who had no idea how much history he was rubbing shoulders with, pushed on. From Rocky Pass, on a rambling journey after goats and grizzly bear, they followed a route very like the modern South Boundary east over Cairn Pass, stopping to build the huge cairn that gives the landmark its name. Aiming for Old Bow Fort, an even-then-long-abandoned HBC ruin thirty miles northwest of today’s Calgary, they left the future trail and forded the Brazeau River. This took them into tougher country and they struggled through deteriorating weather to find, and eventually cross, Job Pass. With horses falling they were relieved to strike the Cline River and from there the Kootenay Plains, from which the rest of their trip was over travelled (if not civilized) land and relatively straightforward. Lord Southesk, after being initially impressed, found the Front Ranges more oppressive and frightening than beautiful, less than he dreamed, was glad to escape with no more harm than wasted shot and three horses lost, and spent the rest of his life looking back on that journey. These are emotions I think we all understand.

Lord Southesk went on to publish poems and novels, which hiking bloggers would if we could, and his exploration days were up. He had hardly hung his coat back in Scotland before he’d re-married and become a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, though it took fifteen years for him to put his diaries into publishable order. His fourth son, the Hon. David Carnegie, was a remittance man in Australia who in a short life had even more extraordinary adventures than his father. The ninth earl’s grandson married into the Royal Family, following which the Carnegie patriarch is now the Duke of Fife. Yet it is rather pleasing that, when the pioneer’s great-great-grandson retraced some of his ancestor’s steps in 2009 his father was still alive, and so the future Duke stood by his ancestor’s cairn with his family’s courtesy title, the Earl of Southesk.

Those of us who follow in his steps have, mostly, an easier time. But the South Boundary still has a reputation for being half-hike, half-exploration, for involving route-finding and a fair proportion of technical difficulty. Imagine my joy to find how overstated that was. Lord Southesk wouldn’t have recognized the place5.

Intermission (or: Day 0)

The story so far: a tubby man carrying a hiking chair has resolved to hike the South Boundary Trail, a 75-mile backpack on the edge of Jasper National Park between the current northern trailhead at Rocky Pass, near Alberta’s Whitehorse Wildland Provincial Park, and the southern trailhead at Nigel Pass trailhead, which is actually in Banff National Park. This epic Jasper journey that neither starts nor ends in Jasper is 75 miles on foot but more than twice as far by road, including some gnarly gravel, and typically involves a horrible three-hour taxi ride or two-car shuttle. The tubby man went to Jasper with no car, so his scheme was to shorten the horribleness by hiking the Fiddle River trail from Miette Hot Springs, taking him to within 11 miles of the Rocky Pass trailhead. We pick up our tale at Whitehorse Creek Provincial Recreation Area, the Fiddle River trail in the rear view mirror after three nights in a tent, with our correspondent eying up the 11-mile road walk to his next trailhead and dreaming of not actually doing it.

Starting at 10 PM, my civilized frontcountry camp got a cute little mountain storm. Not serious, just sputtering showers and lightning that was seen rather than heard. I had hoped the weather would dull its own malice for a few days, but no such luck: it was beautiful when I awoke but supposed to rain again overnight.

Sleep had been a bit rough. My tent was too warm and, for lack of safe food storage at the drive-in camp, full of Ursacks. The sole of my left hiking boot was still working its way off, and to add to my Petty Gear Annoyance list, the button fell off my pants. The pants were Prana Stretch Zions, an old and well-worn pair, but the little cap over the staple that held the button on had been lost somewhere along the way, and the staple had gradually unbent until, at certain angles, the thing would just slide off and fall to the ground. I had pliers in my repair kit and did a hack-job fix that, with awareness of the issue, kept my pants up for the rest of the hike; an important thing, since my backup pair was shorts and I did not want exposed calves on the trail to come.

Three nights in, a list of nuisance problems, and I wasn’t even on the South Boundary yet. I had hiked an entire trail and felt like I hadn’t started. A bad place to be, mentally, but at least this would be the last day of The Approach. I had made it to the Grave Flats Road, and in ten miles plus change I’d be sitting at the Rocky Pass trailhead, ready to do the hike I’d actually come out here for.

The road walk begins. Flying up the gravel at a good pace. The rain is supposed to come but it’s lovely for now. It is dry and dusty all the way. There are water sources, miles apart, but it’s a road and it tries to go over them. Every drink is a feat of patience and careful footing.

The Grave Flats Road, and what a name that is, is an interesting place. I had expected a rough mining road and it is rough, but the actual mining road is a totally separate, bitumen-surfaced road that runs parallel to the Grave Flats Road for miles, even to the point of sharing bridges, but always carefully and clearly physically separate. Whenever an access point from one road to the other exists it is gated and locked. It was a Saturday, and mining here ended in 2020 due to declining reserves, but Teck still has cleanup activities at the old mine and aspires to open new operations in the area; the traffic was therefore decent, but almost out of sight behind the berm.

Nowadays, the Grave Flats Road itself exists pretty much entirely for recreation. It once ran south as far as Nordegg, allowing easy access to Red Deer or Saskatchewan River Crossing, but the road east of the Rocky Pass trailhead washed out in 2003 and Yellowhead County has no plans to repair it. Google Maps says it’s a passable route. Please don’t trust Google Maps out here.

Tracks in the dust. Horseshoe prints, and prints that might be boots. Maybe I’m not the only one stupid enough to… wait, an engine! Turn, face the truck, stick my thumb out, try not to look smelly. There is a man, his wife, and two dogs, crammed hilariously into the standard cab of their pickup. They do not slow down. I don’t blame them, give up, and wave. They wave back. Their truck has Ontario plates. Probably an interesting story if I could have heard it.

If only there was a hand signal for “I would be very happy riding in the bed of your truck.” Oh well. The Canadian Rockies Trail Guide says that this road is seldom-trafficked but drivers are usually friendly to hitchhikers. Still, they need to be able to physically fit me in the vehicle. If I have to I’ll road-walk the 11 miles, uphill, I’d just really rather not.

Walk on. It’s a Saturday. Despite what I’d been led to believe, between Whitehorse Creek and Cardinal Divide there’s decent traffic. But it’s no good to me at all. ATVs. Dirt bikes. Quads. Six-wheelers. Again and again I hear a motor, again and again it’s something that even the best-intentioned driver couldn’t pick me up with. I wave a lot. I don’t actually like hitchhiking, and lack conviction.

The road goes up, then down. Signs warn of 6% grades. Ooh la la. So far it’s not bad, and the gravel surface is reasonable. It’s just dull. I am pushing on at good speed and wish it was over. There are hints of the old railroad, the Coal Branch, which once served the old mines in the area. A bridge from 1931 would be in great shape if the tracks connected to anything, but after a 1950 flood of the McLeod River the damaged railbed was abandoned in place and several mines closed. The usual story. Everything gets a bit worse.

A mine employee happens to cross over from their private road as I pass. He has to get out and open the gate, and we chat. Beautiful day. A grizzly sow with two of last year’s cubs is in the area. Oh joy. Any chance of a lift? Sorry, they wouldn’t let him. I didn’t really think so, and I thank him anyway. Nice guy.

It occurs to me that if the grizzly eats me, my family could probably sue the mine for quite a bit if I write that encounter down. But that would mean stopping, pulling the diary out, and I just want to get this done.

At least it’s not too hot. More quads, more ATVs. Is this the ATV capital of Canada or something? Four miles in, making good time, but the worst is yet to come.

Another truck behind me. Stop, thumb out. Dad, mom, daughter crammed into the standard cab. Didn’t I just see this movie? They stop anyway.

“We’ve got a full house here, but would you ride in the back?” Yes I would.

Comedy ensues as the first gentleman of Alberta can’t get the truck’s bed unlocked for five minutes. His buddy, in the also-full truck behind, comes up and they swear at it a bit before getting the cover off and giving me room to leap in. “The word ‘hero’ is thrown around a lot these days…” I literally say. The bed of the truck is not too full and beats the hell out of walking. We are off.

The way to experience the Grave Flats Road is in the bed of a pickup truck. The bumpy ride passes a surprising number of Alberta backroad points of interest: a STARS air ambulance base, some sort of ATVers camp atop a bluff, more unreasonably thoroughly-engineered tunnels and bridges with shitty loud decks, increasingly terrible road that rises, narrows, and roughens. They blast the horn through the tunnels and have a great time. Between my fat ass and my fat backpack there must be 280 pounds of hitchhiker bouncing around this guy’s truck and I try not to move too much.

After much enjoyable passenging we stop five miles later at Cardinal Divide, their destination and the local beauty spot. I’ve got more than a mile to go but it’s all downhill from here and I am terribly grateful. Cardinal Divide is very nice, with outhouses and information kiosks. People with trucks and quads, recognizable from passing me on the road, are eating brunch or drinking beer and looking at grand mountain vistas. I restow my pack, which had changed shape after its paint can treatment, and hike the mile and change downhill. The road after Cardinal Divide is simply appalling, even compared to what was before; it’s a nuisance to walk, let alone drive, and everyone who said you want a high-clearance vehicle here was correct. I would also recommend a spare tire. Still, one sees the provincial park sign, and then one sees the trailhead almost immediately after, and then I was eyeballing the first day of the South Boundary Trail. The plan: camp at the trailhead, do Rocky Pass tomorrow, and finally get my hike started.

The only problem is, thanks to my ride, I have arrived before noon.

Push on over Rocky Pass? I have time. Against this: despite my ride I have hiked five miles today, and they were easy but not free. Gaining a day isn’t worth anything, since my schedule is fairly firm: even if I finish the South Boundary in half the time, my train home leaves the same day. If I really did save four days I could pop to Edmonton or something, but I soberly decided a while ago that was pretty much impossible, and saving two days would be just spending money. Moreover, the weather forecast from my Garmin inReach is bad for the afternoon and evening, but good now and decent for tomorrow when I’ll have more time, energy, and patience anyway.

Finally, the Rocky Pass trailhead is surprisingly good camping. It’s in neither Whitehorse Wildland nor Jasper parks; this is a Public Land Use Zone, and apart from specific restrictions you can do just about anything in one of those. Hunt, fish, hike, quad, and camp. There are several decent places for tents, more than I’d find on most parts of the South Boundary Trail, a good stream for water, and a couple of views. In fact there’s already a party there, with their Woods tent, their three chairs, their full kitchen, and their sky tarp, but no people. The downsides are the lack of bear hang and the vehicle traffic, but one gets used to one of those problems and can choose to ignore the other.

So I pick a spot, set up while it’s sunny, and waste almost an entire day sitting around, reading, writing, and watching the birds. It’s pretty rewarding, actually.

There’s a lot of company here in the ass-end of nowhere. A hiker in what I think is a The Trek t-shirt comes down around 2:30. Despite wearing a t-shirt for a hiking website, he’d actually been hiking, popping up to La Grace the previous night having already done the entire South Boundary the month prior. I’m not sure what else I could have asked for in a campsite visitor, unless he’d brought a case of beer with him. He is in a hurry—and since he doesn’t have a vehicle I understand why—but we briefly chat. He found the trail “definitely passable,” which I guess I’ll take, and while a month ago the bugs had been apocalyptically bad, they had died down hugely since and he’d had no problems the previous night. He had to bust it up to Cardinal Divide and find a way back to civilization, so I didn’t detain him, but it was a valuable chat all the same.

Many ATVs and quads drive in, hour after hour. Dozens. Some of them tow trailers or carry big loads and are obviously in for a few days; others are just having a drive around, since from here they can follow good track and seismic line as far as the Cardinal River headwaters. The other campsite turns out to be two people on a quad, who return late in the afternoon, but most are camping deeper in the woods. It is a huge, varied crowd. I think of some of the trails I’ve hiked that were just too crowded to be fun. Do quadders ever have the same thoughts?

An SUV pulled in and a couple got out, to spend the night I would have thought at that time of afternoon, but instead they pulled out light packs and started hiking back towards the Grave Flats Road. Well, I said hi, and learned they were on their way back to Cardinal Divide themselves, there to drive their second vehicle to Nigel Pass and hike the South Boundary Trail in the opposite direction of me. At that point I was pretty sure God was telling me I had been right to stay the night. We calculated we should meet Wednesday at Cairn River—and it was at Cairn River that their previous attempt at the South Boundary had gone wrong due to difficulties route finding, as the trail is effectively gone much of the way to Cairn Pass camp. I promised that if we did meet I’d try to tell them how to get through. I found the idea of running into some strangers almost by appointment in a few days on a 75-mile trail rather pleasing.

The night rolls on, the storm rolls in. A wicked thunderstorm arrives, boxing the compass with its terrible noise. A few of the strikes seem horrendously close, but I am in my tent by then, occasionally looking out the fly through the rain at the quads heading back out again. It lasts not much more than an hour, but it is a great, ominous way to close my very, very long trip to get to the South Boundary Trail.

The first morning of the hike was beautiful and clear. The only clouds were in the direction I wanted to go, but the only constants of mountain weather are that it is inscrutable, and that I will regardless attempt to scrut it. My tent was very wet, which saved me the trouble of being annoyed if it got wet again later, and as the weather was pleasant at breakfast but might well have deteriorated I resolved to hit the trail rather than give the thing time to dry. So I shook the water off the fly as best I could, shoved the wet tent into its now-also-wet bag, ate a coconut and chia oatmeal with grim determination, and powered out towards the pass at a brisk and early, well, 8:30 (it was cold!).

Every leaf, every branch, was shimmering with moisture, and a wet hike was in the offing even if the rain stayed away, but since there’s wasn’t much I could do about that I thrust me jaw out and marched down the seismic line towards Rocky Pass6.

A seismic line is a swathe cut through the forest by oil and gas prospectors, who need a clear corridor so they can set off explosives in the ground and see if there’s petroleum nearby. Such lines have one job and aren’t meant to be permanent but many, like this one towards Cardinal Pass7, have been seized upon by hunters, trappers, and other outdoorsmen as picture-perfect ATV tracks. This particular one rips in an arrow-straight line towards Mount Cardinal, a great stone pinnacle visible down the clear track for miles. Quadders ride this line then turn right towards the headwaters of the Cardinal; hikers turn left towards Rocky Pass, a mile or so in8. The seismic line, though muddy and tire-scarred, is about as easy as walking gets.

At one time, the turnoff to Rocky Pass was a puzzle for South Boundary hikers. If a visitor didn’t arrive already knowing that this little track leaving the seismic line between two rocks was the right way, there was every chance to miss it. Then, in 2020 or 2021, someone added a trail marker. It reads “Rocky Cardinal Pass Horse,” signed by A.H. and D.A. of the NTR then screwed into a tree over an old blaze, and is completely unmissable. All of a sudden navigation becomes much less dramatic than the trail’s reputation would have led you to believe.

This would be a theme of the entire hike. Not that you can’t get lost, or take a wrong turn; I did myself, more than once. But the bad old days when you said “I not only don’t know where the trail is, I don’t really know where I expect it to be” are disappearing behind cairns. Eventually they’ll fall down, the flagging tape will fade, more of the trail will slide into the river, and the real route-finding will return, but right now the South Boundary is, for the first and maybe only time this century, getting a little bit easier every year9.

Another theme was that, as I left the literally-straightforward seismic line for the horse trail, it was with a twist in the pit of my stomach borne of anticipation that this would be where the “real hiking” began. The horse trail was easy. The day was easy! The hardest part was getting there, with most people driving to Nigel Pass, parking a car there, taking their second car over the frightening roads to Rocky Pass, and banging out the day’s hike. More people would camp a night at Rocky Pass trailhead if they knew it was an option, and now you do.

Rocky Pass is really fairly low, a deep cut in the Nitkanassin Range; it stands out on the National Geographic map like a smear of green crayon. It’s middling long but not terribly exposed. It is, at times, work. For example, the shoulder-high willows; I had thought I was getting used to them after the Fiddle River, but I hadn’t seen them like this. Willows stretched over the trail like a lover’s fingers, stroking me in passing. The track is well-defined, but the canopy of the willows overtop makes it invisible from more than a few feet away. After a rainy night they collect water, droplets cling to every leaf, two dozen leaves stretch over the path per willow, and there are 500 willows. It is like going through a car wash for hours. I had consciously left my rain pants at home, because I never, ever wore them: I would have worn them today. Horseback riders don’t need to worry about such things, though I’m not sure anybody asks the horses. Hikers do.

Willows with even the modest trail brushing that, say, the Rockwall gets are very different flora. Nobody’s going through and cutting back the growth in the backcountry every year, but getting to it every few gives enough room to shimmy through, or let your left side get whacked for a bit then your right side; there’s no escape on the South Boundary, when you simply have to power through the water for as long as it’s there. It’s not unbearable. If you aren’t prepared to be very, very wet when on a two-week backpack in the mountains, you aren’t prepared. I got very, very wet.

The trail is muddy and rutted from horses, hikers, and the boggy soil, and obscured by the foliage; passing through the meadows is eyes-down time with a vengeance. Which is a shame, because it’s also open country, and when I did look up, and saw the mountains surrounding the Cardinal River valley, it was worth it. It made me stop and stare, with a smile, and as an excuse for the delay I’d smash the next few willows along with my hiking pole, knocking the water off. I don’t know if that made any difference but it felt good.

Then, rivers. There were four fords of the Cardinal River, and pretty easy in mid-August after a rainy night. Mostly I rock-hopped. One foot went in, once. There was a spot where I planted my poles in a deeper channel, used them as leverage, and took a long step from rock to rock. This sort of rock-hopping is both slower and more dangerous than quick calf-deep fords, and thanks to the willows I was soaked through regardless, but what the hell. The Cardinal is a very attractive river, and well-cairned when the route happens not to be obvious at a glance, which it almost always is.

At one unmarked trail junction with options left and right, there are no markings; left smells correct, and is. But my GPS track went right and I decided to go check it out, only for the GPX file to take a U-turn in less than five hundred yards. It’s interestingly maze-like out in the public land use zone, with the quad and horse tracks. The right-hand trail doesn’t seem to join back up with the left, and the best guess is that it heads up in the direction of Cardinal Divide. Probably you’d reach that right-hand trail if you followed the seismic line further10. Anyway, it’s not worth exploring on foot so just turn left; you’ll know you’ve passed the fork in the right direction when you hit an obvious outfitter camp, well-used and well-cared for, though inconvenient of water access.

Climbing Rocky Pass is like bankruptcy. It happens very slowly, then suddenly all at once. Shortly after the last ford I drove uphill on what looks like a seasonal cascade, braided on all sides by people trying to avoid the water and the flow making its own decisions. The trail is clear, well-maintained, and very direct. Whichever mountaineers laid out this track had never heard of switchbacks; it goes straight up along the path of least resistance which, as paths of least resistance tend to be, is at least short. The real gruntwork driving up the stream bed gives way to merely standard Rocky Mountain gruntwork in a few minutes.

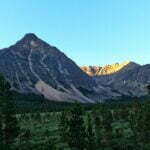

Rocky Pass is not high, but it feels long. Willows are your constant “friend.” Eventually you break through to the subalpine. Rocky Pass is named after the Rocky River, not its physical characteristics; the walk is brushy most of the way. But it is handsome brush, with the Medicine Tent valley ahead of you, the headwaters of the Cardinal River to the north, and great big slabs of rock of the Mount Mackenzie massif to the south. There’s enough room in Rocky Pass for the eyes to feel as stretched as the legs; it’s not some great gorge you’re negotiating a route through like Nigel Pass, it’s just a big, lovely thing, long enough that the views stay varied. You can day-hike this, if you can get to and from the trailhead, and that would probably be fun.

The pass is marked by the yellow national park boundary sign, a couple survey markers, an ancient warning on bringing firearms into the park that’s pretty much in a tree now, and that’s your whack. A few ruins of cairns at high points on the way perhaps reflect other travelers’ ideas of what the high points were. Why not come and build your own? They may wind up naming the pass after you.

There are rocky parts of Rocky Pass, if you’re patient. But be patient in any event. The pass is infamous for how it winds up and down, up and down, in generally non-strenuous but emotionally aggravating ways. You pay a small price for the variety. The most unfair part of Rocky Pass is not that straight-up ascent but, immediately following a spell of easy forest walking, a 90-foot valley on a steep, slippery, narrow, pebble track with oblivion on your right hand. It is a very annoying down, and an even more annoying up, and then right in the middle of it there’s this pretty little falling stream which is pleasant and contemplative even if you don’t need the water, and you can call that a metaphor for the hike if you choose.

After this, you head down. Is it coincidence, or is it old engineering, that the half of the Rocky Pass trail in Jasper National Park is a pleasant, well-switchbacked trip down to the Medicine Tent River (the trail is actually in good shape, too), and the half of the trail that’s in a public land use zone barges straight uphill? The switchbacks are appreciated, for it felt a long way down, until I walked almost smack into one of the most famous signs on any trail in Jasper National Park: a decades-old wooden sign mounted high on a tree. There are two arrows pointing right that say “Jacques Lake” and “Jasper,” and one that points left and says “Cairn Pass.” Hand-carved and painted, edges sanded, and nailed to a tree by somebody who probably isn’t with us anymore. It’s beat up. The bottom half of the “Cairn Pass” lettering was lost who knows how long ago. It’s also wrong, since you haven’t been able to get to Jacques Lake or Jasper from that trail in almost twenty years. But it’s beautiful. It says something much more important than directions nobody needs: it says that this is not some up-to-date, officially-cared-for tourist route. This is an old place, and everyone who has walked or ridden it was doing something a bit special, and now so are you.

I barely remembered the details of Rocky Pass until I went through my photos but I remembered everything about that sign.

The South Boundary has a reputation for being unmaintained, which isn’t quite fair. The Rocky Pass trailhead is well out of Jasper National Park’s way, it’s hard to imagine the last time an official trail party would have come this far, but by Medicine Tent camp there was fairly fresh-cut deadfall beside the trail, within the past two summers. Horse parties? Maybe, but horse parties don’t stop at that campsite. No matter who gets the credit, the trail was in perfect shape. My first steps on the classic South Boundary were about one hundred yards from the old sign to Medicine Tent camp (turn right), and they couldn’t have been simpler.

Medicine Tent is lovely. There are three good tent spaces, which is a lot for the South Boundary. A couple more wonderful old hand-made signs, still fresh as a daisy. Open, but wooded pleasantness, and a pretty river with mountain views. I truly enjoyed that campsite, which is funny because it has a reputation for being sort of “blah.” Yet some of other people’s highlights down the trail, I didn’t like at all.

There is a bear pole, such as the one that thwarted me at Fiddle Pass a few nights earlier, a wooden staff way high off the ground nailed across two trees with their lower limbs removed. The concept here, which is tolerably simple, is that you throw your rope over the pole, attach your food bag to the rope, pull it up to a bit below the level of the pole, then wrap your rope around a tree trunk. The only catch is throwing your rope over the pole. I knew to put a rock in a bag, and attach the bag to the end of the rope, to give it some momentum, but then I’d whip the rope around and throw it overhand, whereupon my rope-rock would get caught in a tree branch or go off the crossbar or do anything but what I wanted it to, and I cut my finger open. At Medicine Tent I tried a gentle, swinging, underhand toss. This worked much better, dissipating days of anxiety in a second. Not that I’m terrified of sleeping with my food (I use both Ursacks and odour-proof bags) but it’s one risk less and, well, they take up a lot of room in a one-person tent.

Medicine Tent also has a privy, the legendary “pole and a hole.” It’s very like the bear pole described above, only quite a lot lower. You drop trou, sit on the pole, dangle the essential region off the end, and a pit beneath receives the necessary sacrifice. Given that we’re literally talking about an open sewer these rustic appliances are talked about with a lot of affection by backcountry veterans, and they’re quite right. The one at Medicine Tent won’t make the annual calendar: the hole is filling and the log is rotting, which might mean a very bad day for somebody in a couple years, but it’s an awfully comfortable way to do one’s business. Much more comfortable than an old, collapsing outhouse, or those three-way thrones on Skyline. Warmer on a cold morning than the green plastic poo capsules. They fit into their setting very well. I fully endorse the pole and a hole, without reservation, as long as somebody’s able to bring in saw, hammer, nails, and spade to move it once in a while.

I got to know this pole fairly well because, having gotten my tent set up, bathed, done some laundry, and had a drink, in the late afternoon I felt a sudden need, went to the privy, and had a more dramatic time than I would have preferred. It wound up being a one-off; I blame stretching half a packet of dehydrated beef an extra day after I’d opened the package. I had thought my Minor Gear Issue would be my phone getting soaked by the willow bath and hallucinating that it had a headset connected but no, it turned out to be my colon.

Like any good Minor Gear Issue, it was fine but provoked anxiety at the time. When alone in the woods I talk to myself, a lot, and I spoke very animatedly with the trees about my large intestine, and then I turned around and a hiker had walked in. He was spruce and fit and carried lightweight gear. We were surprised to see each other. I said I was staying the night. He asked what I was hiking. I said “the whole thing,” meaning the South Boundary, but he thought I meant the Southesk Loop, which was about the most flattering mistake I could imagine. The Southesk Loop really is wild; it follows the South Boundary trail between the Rocky Forks campground11 almost all the way to Cairn River camp, then turns south and plunges into the wild. It’s supposed to be very pretty and very remote, with at most a party or two passing a year, and there’s never been an account of hiking that loop that didn’t boil with frustration at the total lack of trail, the endless fords, and the man-high willows. I’m not that sort of hiker, I like having a nice time.

This fellow was starting his Southesk Loop that day, so while he was checking out Medicine Tent as a stop for the end of his loop his real goal was La Grace, another five miles east. He told me he always wanted to do the whole South Boundary. I told him he could keep the Southesk Loop for me, thanks. He left, speedily, and I’m almost sure it wasn’t because he didn’t want to spend the night at a campsite with a guy who had been talking to himself about his bowel movements.

Once he was gone, it was back to worrying about my stomach, but the sheer time it took for conversation had already taken the edge off my fear. I ate a meal bar, then a gentle dinner, and all was well. By bed time, when I got my phone out and watched my stories (trail videos of other people’s hikes of the South Boundary, so I could remind myself what lay ahead), I was quite at ease. I was right to be.

It was a fine mountain morning. The sun was pretty much out from behind the cloud. I felt good. Medicine Tent camp was right up my street; La Grace camp is said to be a dog’s breakfast of a site, the worst on the trail. It was going to be a short day of hiking, less than six miles and mostly easy, with only one washout, a warden cabin, and a very modest 900 feet in elevation to distract from the short forest stroll. It all added up to a lazy morning in camp, reading, enjoying a leisurely breakfast, even doing some solar charging. I didn’t start hiking until 10:30 in the morning. As an experiment to deal with the boot sole that was trying to come off, I wrapped some Tenacious Tape around the front to try and lend it some robustness. I didn’t really expect this to work and sure enough it didn’t, but it would have saved me something more drastic that might have impeded resoling the boots later.

The trail here was, after five nights of hiking, my first taste of the true South Boundary. There were long rocky gaps to sniff my way over, there was one washed-out section. However, there’s a funny thing about the South Boundary Trail. It’s not at all busy, in fact it feels very isolated, but also more popular than I’d have thought. Some of this is the sense of history, the deepness of the track, the age of the signs that take more than a few years of neglect to really wear, but not all of it. New boot- and horse-prints lie heavy in the mud, heavily outnumbering the moose and the bear. Big deadfall is seldom cut away, but the routes to get around it are well-worn. Moreover, today, when I reached any of those rocky wash-outs, either the trail or a cairn, built in the last couple years, was always in sight to guide me without even perfunctory scouting around.

On the trip I passed the local attraction, Medicine Tent patrol cabin, so close to the trail you can fall sideways to reach it. The patrol cabin is a gorgeous little structure in a gorgeous little field, two and a half miles from Medicine Tent hiker campground and en route to Medicine Tent horse. It has a white fence on the patio and a couple old benches to ease the feet of the weary traveler. It also has, besides the inevitable padlock on the door and the “No Trespassing” notice, a sign explaining in both French and English that there are no emergency communication devices in the cabin and instead giving the Park Dispatch phone number, which would come in very handy in that sort of emergency where you can hike twenty miles to the nearest point with cell reception. It reminded me of the Chilkoot Trail, where notices on warming cabins suggest that in case of emergency you blaze a trail across a mountain range and use the phone at the Fraser border post.

Wardens securing their cabins makes perfect sense. They need to keep the bears out; new tin roofs are a relic of a particularly persistent grizzly who ripped the shingles off many of these cabins a few years ago. They also need to keep the assholes out, as these cabins are well off the beaten path and a warden on horseback will rely on the things that are supposed to be in there and have no easier a time bringing in last-minute supplies than you or I. The signs, locks, bars, and window coverings, however, do turn what should be a charming, pastoral cabin into something more institutional, governmental, hostile; a negative vibe that could not have less in common with what happens when you win the lottery and actually meet a warden or a team of volunteers at one of these places.

The hike to La Grace, in short, is one of those stupid little hikes that makes it seem hardly worth packing up the tent to do it. It does provide a breather before a spell of more interesting days: the climb over Cairn Pass, the real routefinding12 of the Cairn River washouts, the tricky, patience-testing navigation around the Southesk River to its precious suspension bridge, and the potentially-nasty crossing of Isaac Creek. It provides a few nice views of mountains across the Medicine Tent. It was all very simple. Even the part where you scramble down and through the washout of the trail is easy when you know where to go, and the cairns tell you: stick to the shore, don’t ford, the trail will come back soon. It’s easier than the equivalent washout on the Fiddle River trail.

When I was a mile or so from La Grace, a couple hikers walked past. They were spruce and fit and carried lightweight gear, but by this point we were not surprised to see each other. They, too, were doing the Southesk Loop—finishing it, in fact, having gone the opposite direction of the man I met last night. They had seen him earlier in the day, so had half-expected to run into me. The Southesk Loop seems to be the new hot spot for people seeking solitary adventure, like the South Boundary is now too mainstream, although the inherent logistical convenience of a loop hike probably helps. They described their trip in brief and my interest in trying it, which was already close to nil, went down further. The willow-bashing up the Rocky River sounded like a wide-awake nightmare, distinctly much worse than that on the South Boundary which was already enough for me. They had Medicine Tent booked, but were inclined to blast over Rocky Pass and go home. Who would blame them?

La Grace13 camp is better than its reputation, but problematic. The campsite is literally on the trail, all but inviting four-legged passers-by to take an interest in your tent. The water is an inconvenient walk down through willow. Each of the (very few) tent sites are prettily perched beneath trees killed by pine beetle, just waiting to drop big branches or their whole trunk onto your tent, and as always the eating area and tent spaces are snuggled up nice and close. The pole-and-a-hole is miles off and nearly full. Like virtually every campsite on the South Boundary, you can’t see the thing it’s named after from the campsite; Mount La Grace, to your north, is totally obscured by trees.

But. When you’re sitting down, eating or reading and enjoying life, it’s a pretty place in a mountain forest. The weather was turning grim on me but La Grace was not itself dour at all. Certainly, it is by South Boundary standards a poor campsite, and if I were to skip one it would be this. But it has, barely visible, a thread of charm. Its total lack of pretension gives it something I can’t define; it is simple, it is utilitarian, it is even a bit hazardous, and you are in the mountains, and it sort of all fits together. No, don’t feel obliged to stop here, you can see it all from the trail anyway, but the place has a soul. I find my memories of it are rather warm.

The weather contributed the only gloom. Thunder was echoing distantly by dinner time, though the sun shined on camp and I ate in no particular hurry. The rolls and booms once again came from every direction, probably from a great distance as systems of weather were driven together above mountains by powerful winds. Overhead it wasn’t nearly so bad, but lest I think I was in some permanent zone of calm I noticed at this point that two trees in camp had clearly been killed by lightning. The sounds closed in, as did the clouds. The rain, though fat and prolific when it came, was only ever off and on, twenty minutes at a stretch: the thunder was just on. I hunkered down in my tent, and the spirit of La Grace was lost to me.

Still, heavy rain with breaks is ten times better than just heavy rain. One nice thing about camping alone is leaping out during the lull, buck naked, to have a slash, leaving the tent light on behind me.

It seemed rather unfair to wake up after a night filled with that much weather, stick my head out of the tent, and see it was still overcast.

Having slept quite badly through a night of thunder and rain spells, I stirred more from guilty conscience than any desire to experience the world. Cursing, grumbling, I started to pack while it wasn’t actively pouring, and no sooner did I have my sleeping pad away than the rain came back and I waited a while before taking down my tent.

The Garmin weather forecast, which had been surprisingly accurate to date, predicted a bad day, though not a terrible one. The next day was supposed to be enough of an improvement that I toyed with the idea of staying in camp and doing a two-banger tomorrow but sitting inside a tent, listening to the rain and the wind, obviates all of La Grace’s virtues and accentuates its vices. I didn’t really want to lose momentum in a place like La Grace, but I also didn’t really want to do Cairn Pass in the cloud. Given two unpleasant options, I opted for the one that gave forward progress.

I packed as best I could without getting water on everything, and did a pretty good job, though there was so much damp about that I had to shove my poor stuffed beaver into the clothes bag, crushed like my hopes. Breakfast was sullen, though hot, and then I was away, not all that early but mostly dry and entirely alive.

Objectively, Cairn Pass is not difficult to reach. Fairly high—the highest point on the South Boundary Trail—but gradual. It’s not a long day of hiking, either. In equivalent conditions it may be easier than Rocky Pass.

However, any pass can suck in the rain, hiking with no tree cover, being soaked without impediment, wind sucking away your dwindling warmth, cloud so low it veils the way, and lightning, in an area where a hiker wearing a metal-framed backpack and holding aluminum trekking poles might be the most prominent point for a quarter mile. Then, there were the willows. Chest-high, shoulder-high, head-high, and as always not cleared back from the trail. It had rained enough overnight that they were dripping with malevolence, and soaked me through long before the rain started back up. This was very far from the worst sort of day, but it wasn’t great.

It was so grey. So dreary it was hard to believe the mountains could ever be pleasant. The weather forecast said that the weather would be bad in the morning, bad in the afternoon, maybe a shade less bad in the evening; there was certainly no point in hurrying. Emotionally, when I got my pack on, I saw that it wasn’t raining just at the minute so I balled it, and went almost as hard as I could.

This all worked with the motto of the day, which was “Over the Hill!” It was hike 7 of 14 for my trip, leading to camp 7 of 13, over the highest point of my hike: a purely moral milestone, but a truly perfect combination. After Cairn Pass, it was all downhill from there. Over the course of two weeks in the woods I found it helpful to have some near-term target to aim at beyond simply another day’s hiking, some mental slogan that reminded me I was making progress, that every day really was an improvement on the previous and that at this rate I would eventually be home. This would be a good one. The day when I stopped counting up and started counting down.

So I went. I took few breaks and few pictures, none of which really came out. On the Rockwall I’d had a much happier day crossing a pass in the rain, and there’s a grim, even awe-inspiring beauty on days like this. I felt very small within God’s creation, getting above 7,300 feet elevation and seeing how close the clouds pressed on the great mountains around me, seeing how trees and brush felt powerless next to something as ephemeral as the weather. The Medicine Tent Lakes, beneath the gloomy skies and shrunken in late summer, look trivial but pretty. Glistening willows are infuriating, but they are also attractive plants. At one point, just before entering the pass, they rose up literally man-high: they formed an arch over the trail high enough that I had to consider whether to bash through or duck under, and squatting to peer beneath their dripping canopy made Cairn Pass look like a secret place veiled from normal eyes.

I took few memories and concentrated on leaving footprints. The pass is long, willowy, uphill. The rain was back on by the time I emerged from the trees, though not severe; there was a quarter-mile run with rain but no willows, and I realized that I was dryer than I had been willow-bashing with no rain. Still, I was tired, and though the hiking was grim I was enjoying the scenery, and at one point I lost the trail. A typical thing to happen in willow country; it bent left and I missed it, rampaging ahead. In the pass the ground was almost always covered in willows, but the scenery was clear to a reasonable distance, and I had a pretty good idea what I was trying to do, so I went forward rather than turn back. It worked out fine, and I cut across and struck the trail again. But it cost me a selfie at the “Cairn Pass” sign, which I must have missed, and willow-bashing where there’s no trail is marginally wetter than willow-bashing where there is. I bore left through trackless willow, and at one point fell into a hole, up to my waist: an old bear-digging or something, one moment I was walking forward and the next moment thump, down I went about four feet, miraculously completely unhurt but perplexed for a few moments before I managed to lever myself out through the willowy, wet, muddy crap with my trekking poles.

Eventually bumbling back to the trail, it was a hard descent for the last mile to Cairn Pass camp. Hiking briskly kept me warm. I was soaked inside and out; the only time I remember being wetter was when my tent flooded and broke during a storm on the West Coast Trail.

I never did see the Earl of Southesk’s cairn. On a clear day, one needs sharp eyes or binoculars. On a grey one I had no chance.

Cairn Pass camp is an interesting place, even besides my relief to reach it. Moose and elk antlers, and the comforts of a horse camp, abound. Water is from a convenient little creek at the western entrance. Tent spots are pretty freeform, depending on the type of risk you prefer. The one I liked best had a big pile of bear scat in it so I took the runner-up, next to a lightning-killed tree that had no annoying branches so if it went over would hopefully just kill me instantly14.

One of Cairn Pass’s party pieces is its big firepit, but the call for firewood had outpaced the pine beetle and there was next to no hand-snappable timber to be found. Previous visitors had been desperate, or inconsiderate, enough to try burning some of the sitting stumps. A sign on a tree read “don’t burn the tent poles,” referring to the big wooden staves used by the big outfitter camps. Next to the sign leaned a single, solitary tent pole.

Abandoning hope of the comforts of a fire, I set up my tent, got the fly on just about ahead of the next rain squall, and went in it. I emerged in fleece, underwear, and nothing else to eat a quick lunch while I could. But I couldn’t; the rain came back and I fled to the tent, folding the bar up in its wrapper as odourlessly as possible and shoving it inside a dry bag until another lull let me run back outside and eat it. In hindsight this was probably overkill, especially given how strongly my tent smelled like sweaty feet and the pile of misery that was my wet clothes. Sitting out in the vestibule, a great, indistinct lump of moisture and technical fabric. Oh, I had spares, but breaking out something clean and dry when tomorrow’s hiking involved six fords of the Cairn River felt like a waste of a precious resource. One way or another, all that horrible stuff was going back on my body tomorrow. For the moment, it was underwear, fleece, and sleeping bag, watching my stories and reading my book.

Dinner, in that costume, was hurried but welcome. It was then that the most extraordinary thing happened: the sun came out. Only for a moment, but in that moment I was able to look out through the trees and mountains, snap a picture, and see why everyone rates Cairn Pass as one of the nicest camps on the trail.

Then it rained wicked hard, and I got back to my tent.

A cool night, with my watch recording the low in the tent as 42°F (6°C), though I was perfectly comfortable in my down bag. The rain had stopped at around nine and hadn’t resumed. Implication: clear skies? I stuck my head out from under the fly. A beautiful bluebird morning. At last.

I procrastinated in camp, not just because of how lovely Cairn Pass looked in the morning sun, but also because of the grotesque awfulness of putting on my wet clothes, on which the pleasant rays of a cool dawn had as little effect as a mosquito on a monster truck. I made tea for only the second time all trip, admired my surroundings, and sipped it happily, my body gradually warming up the horrible clammy crap I was obliged to wear.

This would be, by repute, a tough day. Mostly downhill, but relatively long and difficult to navigate. The complicated part is that, in 2013, floods of the Cairn River washed out the trail in six spots between these two camps. Routefinding through the flood plains is said to be difficult and, remembering the party I met at the north trailhead who’d been turned back here before, I had a piece of paper and my pen in my breast pocket, to write down information on the route as I (hopefully) followed it.

The willows were, of course, soaking wet. Not as bad as the previous day’s but bad enough. Fortunately, it was such a beautiful day that the views redeemed them.

This is Mount Dalhousie Day. An enormous slab of a mountain to the east, named after the Earl of Southesk’s late friend the 11th Earl of Dalhousie “at whose house my journey to America was first suggested.” The earls of Dalhousie have had their seats in the Scottish Lowlands but Mount Dalhousie shrieks of something wilder, though equally Celtic: crenelated, imposing, imperious, dominant, like a laird’s castle defying Marshal Wade, a line of men with claymores and burning for Bonnie Prince Charlie all but visible issuing from it. It is a great, glorious mountain, one of the highlights of the South Boundary, and for much of the tedious whacking through those willows it is prominently, happily visible. Looking back, I also got my first real sight of the mountain named Southesk Cairn, a less remarkable but still interesting, shallow, scramblable peak. The titular cairn was way out of sight.

It was very pretty. The power-wash of the willows was annoying, but as I was wet already and had six fords of the Cairn River coming up it probably didn’t make any odds. The real inconvenience they caused me was some unknown individual out of the billion chest-high branches I had to batter through snatching my pen out of my breast pocket, so if someone comes across a black Rite in the Rain ballpoint between 2.6 and 4.6 miles from Cairn Pass camp would you please leave a comment. I had to write the rest of my diary in the pencil from my first aid kit. It was murder.

The first spot of trail erosion, coming after the punctiliously-ignored turnoff to the Cairn patrol cabin15, is a simple thing. Down to the shore, follow it two hundred yards, up to the trail. There’s even a cairn in the middle. Easy. The second is no harder. But it’s in here that the trail gets annoying. The willows get worse. And the mud! Great wallowing slimy scummy puddles of ankle-deep muck. Horrible stuff.

Even the trail not destroyed by the flood often nearly was, leading to a great deal of chancy side-stepping. Come see the South Boundary Trail before another three miles of it falls into the Cairn River!

The trail detours, happily, are well-cairned and often well booted-in. Good Samaritan hikers like JJ in the Mountains have flagged some important parts to make it even simpler. The official yellow markers mostly face to the east for visitors heading west towards Rocky Pass, but most hikers go the other direction and therefore the cairns and flagging tend to be easiest for eastbound hikers to pick up. I tried to write these things down for the westbounders I expected to meet that night. In general the fords are easy, the worst being knee-deep and not too swift. There is a rather unfair late-in-the-day up-and-down through by far the most bear-scat-encrusted section of trail I had encountered yet, then the last bit of missing trail immediately before camp. Having picked up cairns no problem all day I found myself a bit unsure there, knowing I wanted to go east but not seeing anything obvious through a little patch of brush. Figuring it could be neither thick nor lengthy, I bulled straight east through the brush. It wasn’t, and when I emerged a moment later it was to look almost right at a yellow diamond, across my last river crossing of the day.

That was where I slipped. Luckily it was shallow; I was carelessly farting around near the shore, moving a bit upstream through ankle-deep water before hitting the main channel. My chair got wet, my butt already was, and only my dignity was hurt.

Cairn River camp is gorgeous. Mount Dalhousie is gorgeous. The stony floodplain is gorgeous. I ate backpacker-chili-no-beef and watched the sun set behind a mountain with no name. The site, like the trail leading to it, showed sign of recent chainsaw work, and there was a healthy pile of wood for burning in a little Parks Canada fire grate augmented by a pretty stone fire ring, on a sunny evening right when I didn’t need it. I had only four problems.

One, my tent got some ants in it. They are active ants at Cairn River.

Two, the people I met at the trailhead missed the rendez-vous. Although it was tempting to think that they had been trapped on the wrong side of the Southesk River by a forest fire or sudden bridge collapse and their not being here on the appointed date was due to some catastrophe that would derail my hike and imperil my life, it was more likely that their math had been off or they were delayed for some reason. I’d spent an hour in the evening making my Cairn River notes out into fair copy, too!

Three, I spent a while looking for the bear hang only to find a cute little cable maybe ten feet off the ground quite near the eating area. It felt sort of pointless, really, though I used it.

Four, my detaching boot sole had made alarming progress leaving the bottom of my foot, having advanced to the second row of tread. It still worked fine, give-or-take catching the occasional rock I would normally step over, but this could change fast apparently. The sole looked like it was splitting off an “inner sole,” within which there were pine needles and dirt but apparently not much natural adhesion. I wondered if the quick river fords were scouring away the soft inner sole, explaining why my problems suddenly accelerated so. Either way it was time to try something else, while the sun was out, boots could dry, and glue could cure.

I had used most of a tube of Aquaseal earlier in the season, repairing my winter tent. The remains of the tube had gone into my repair/first aid kit and it had almost, but not quite, entirely hardened. I knew I should have replaced that before I left. I just knew it.

But that was no longer a solvable problem. I got my boot dry, cleaned out the gap between the soles as best I could without making things worse, cut the tube of Aquaseal up with my knife, forced a few dollops of adhesive from within all the dry stuff, also cut my finger just a bit, added a little bottle of Crazy Glue, bound the toe of the boot up in some clothes line I’d found around camp, put most of my worldly goods on top of it, and left it to cure overnight. I had limited expectations for success but this wasn’t the Pacific Crest Trail. I needed six more hikes out of the thing. That was it.

Bad sleep. Bad mood. The bad boot did not immediately re-deform when I removed its binding; that was a plus. Good weather, another one. There was nothing objective to be upset about, besides the usual worries; I just woke up and felt down. I had never been down in a more beautiful place, though.

Probably as a result I loitered in my bag, loitered in my tent, loitered over breakfast, and loitered all around the campsite. I left at some outrageous hour, eleven or something. Unbeknownst to me I was embarked on a perfect cure for depression—a day that didn’t kill me but might have.

This is the trip from Cairn River to Southesk camp, across the Southesk River, fed by Southesk Lake. The names on this part of the map (and even Cairn Pass and Cairn River are indirectly named after him) has led to many jokes at the expense of the ninth Earl of Southesk’s apparently-colossal ego. Reality is not so bad: in his book, Lord Southesk wanted “the mountain near where the two rivers16 rise” named after him but, believing that such a prominent feature probably already had a name he was unaware of, accepted the more obscure Southesk Cairn as a consolation prize. In the end he got both. Southesk Cairn, prominent on what became a major backcountry route, gave its name to Southesk Pass (also called Cairn Pass), while Mount Southesk named Southesk Lake and in its turn the Southesk River. Southesk camp, which is not on Southesk Lake, is named after the river. Such is how things happen.

Here, the trail was badly burned in 2006, with slaughter easily visible from Cairn River camp. It destroyed probably five miles of the trail, burned the patrol cabin to the ground, damaged the Southesk suspension bridge17, and created one of the South Boundary Trail’s defining challenges. While the active hazards of a forest fire site are mostly gone and the trail through the burn is generally fine, there are several spots where the trail has, again, fallen into the river. This is common in the years after a forest fire, where the destruction of hundreds of trees and the death of their roots releases great landslides with sometimes dramatic consequences. Unlike the Cairn River, the Southesk River trail was fairly steep to begin with, as the trail climbed well above the Southesk River valley and actually left the park for a time, winding around some seismic lines and ATV tracks before returning for a sharp descent back to the river. This means that, while the Cairn River washouts mostly involve splashing through a new river course until you find the trail again, the Southesk slides and slumps make for a very steep, very tricky process of picking out the right course among a thousand options which all look the same while walking at a 30° angle, trying to peer for chainsaw marks and the occasional yellow marker that’s as likely as not fallen over.

Much of the labour could be avoided if you could cross the Southesk River to the less-steep south bank at the horse ford, not long after Cairn River camp. For years, hikers have tried, and for years they have walked to the shore, looked out over the rushing Southesk, and mouthed “oh my God,” their words drowned out by the volume of water, though not as drowned as they’d be if they tried the ford. I didn’t even go look. At the junction, the Southesk already sounded impassible. Supposedly, when the bridge goes out, there’s a better hiker ford east of the bridge site, opposite the warden cabin. As such, bridge or no, the hiker trail was the way for me, as well as a surprising number of horseprints at first. These gradually faded as I scrambled up the shoulder of Saracen Head.

There is a lot of very good advice on how to navigate this part. Watch for markers, for flagging, and for chainsaw cuts, which are a tell-tale sign of human activity. There are a couple places to watch for cairns. Look ahead for where the trail could be, not just underfoot for where it is. But I confess, I got lost. I suspect most people do at some point. It is confusing in there, and the right path turns into the wrong one without warning. So my advice would be: don’t be afraid to double back, even a fairly long way, to the last definite sign you saw, and start over. Also, don’t go high for its own sake.

And take your time. Not just because that will help you get where you want to go. Take your time because this is an astonishing part of the trail. Through the burn, the views of the mountains are almost uninterrupted… but not quite. The scenery, between the death and the new growth over such a grand backdrop, is at once desolate and inspiring, beautiful and dreadful. Walking on the side of Saracen Head, looking over towards Mount Southesk means an ever-changing angle and a unique sort of beauty. I have walked through burns, and none of them struck the senses in quite the same way as this one. Oh yes, take your time.

I was vexed by the two deep rock gullies. I am sure I navigated the first correctly. There was a marker, then a distinct path up the hill; unmarked but also unchallenged by any alternatives. It was steep and loose and I really wanted to take something else, but didn’t find anything I could believe in. So I climbed it, and it was obnoxious, and somewhere up there I went wrong. There were no traces; there were boot tracks, so I wasn’t the only one, but I couldn’t figure it out, and everything was steep enough that I wasn’t eager to go back if I could help it. I reached the second gully and got totally cliffed out, with no crossing imaginable without great risk. Peering around, I squinted at every tree trunk and looked hopefully for a sign, any sign.

I found it. It said “Foot Bridge.” It was nailed to a tree almost by the river’s edge, across the gully, almost one hundred steep feet below me.

Backtracking to a less deadly slope, I started carefully down the slippery gravel, lost my footing anyway, and butt-slid nearly to the trail with nothing worse than a scratched arm. Even now, looking at the GPS track, I’m not sure where I should have gone, but it was somewhere other than where I went. I think, probably, I should have just kept to the shore after the first gully, bushwhacking if I had to, but I don’t know.

From there it was simple. Okay, not simple, but I didn’t get lost again. Following the low line to the “Foot Bridge” sign was straightforward. I still had to hike back up to the escarpment, which led outside Jasper to Alberta’s Brazeau Canyon Wildland Provincial Park, along obscure and often invisible or infuriating trail, but I found if I shouted “show me something!” loud enough it turned up, and the trail felt a hair more real. Sometimes it was just a sensation underfoot, or the direction that the deadfall wasn’t going, but I kept it without too much drama, my short periods of uncertainty were always resolved the right way, and while the climb was a bore it got done. I reached the park boundary, and from there it was simple.

No, really! The burn hardly reached the provincial park, like the fire was under Ralph Klein’s orders, and in there we have a network of seismic lines and ATV tracks, muddy and rutty as hell, but hikers only come in here to do one thing and several good, sometimes characterful signs guide them through. The protocol is simple. Follow the trail. Reach an intersection with a quad track, then turn left, and a clearly-marked intersection is minutes away. Hit another quad track, and do the same thing. The National Geographic map is accurate, but it lacks most of the intersecting trails and is too small-scale to be much use in sorting them out, so you just have to know, and watch for the signs.

I even saw a couple quadders—this on a Thursday at lunch. They were the first humans I’d seen in 72 hours. At first I thought they were heading towards me, but they disappeared around a bend and when they emerged they were clearly heading away, and drove off without slowing. Perhaps they were always going away from me, and never saw me; perhaps they were hunters, trappers, or poachers who had found that chatting to wilderness wanderers was never a good use of their time. I’d have hoped seeing a lone hiker that far from anywhere would have been interesting but not to them. I missed talking to people.

Now the hiking was easy going, though the mud was not fun, and gradually it carried me downhill towards the sound of the river. At length I re-entered the burn, got my first view of the Southesk River in a mile or so, and saw the gentle ribbon of the suspension bridge intact across the river through the burned gaps in the trees. Even though I had always been pretty sure it was there I still shouted “yes! yes!” at the top of my lungs.

The descent to the bridge was via a 170° turn (unsigned but obvious) into what was, at first, a steep but navigable nearly straight line down the side of the mountain, until it became steep but navigable switchbacks. If you slip, fallen timber gives you something to smack into, but it was fine when taken slowly, and the bridge, hanging above a beautiful rocky cleft, was motivation on its own. At the bridge I smiled in pleasure, took my pack off, snapped some photos, filtered some water, took a drink, knocked half the water I filtered over, said “hell with it,” stowed my hiking poles, and crossed the Southesk River into Jasper National Park.

The bridge is traditionally said to have “every board perfect.” I would say “every board is good enough,” which is… good enough. The steel cables and bolts, on the other hand, are perfect; not even rusted. The engineering of the bridge looks simple but the craft and care that went into assembling something that would last is a tribute to the Flying Trail Crew of 2007, whose signature is on the Jasper side. I don’t like heights and I don’t like dodgy bridges, but this one didn’t feel dodgy. It bucked and swayed like a bronco. The experience wasn’t exactly pleasant. But compared to any imaginable ford or log crossing, or the bridges on the American side of the Chilkoot Trail, it felt quite safe. At Brazeau Lake I read a 2017 register entry from a couple that had to carry their Blue Heeler across this bridge, which is about the only way you should have real trouble.

At one time, the trail up from the bridge towards camp was hard to find, but on my visit the entrance was marked, there were ribbons, and the track was well booted in. The route even has three more log bridges over easy gullies, again courtesy the Flying Trail Crew of 2007: when Jasper manages to get a construction team out this way they are not there to play around. I had no problems at all, not even hesitancy. If things are worse on your visit, the goal is to just get on top of the ridge and eventually you’ll trip over the trail that runs along it. It is long, from a meeting with the horse ford to the warden cabin, has several new signs added post-burn, and should be easy to see.

From there I hiked out of the burn and onto easy trail paralleling a great swathe of old, uprooted trees. It went on for ages, like a tornado had gone through, with the trail on one side of the broad corridor. It was a fascinating if confusing area, and while contemplating it I ran into the couple I had met days earlier at Rocky Pass trailhead, and had expected the previous day at Cairn River. One of the other two members of their party had suffered a nearly-evacuation-provoking knee injury, and while they were still in the game they’d taken an extra rest day as a result. I was able to hand over my Cairn River notes at last, and in turn received intelligence on the trail ahead, whose only complications seemed to be a number of downed trees before Isaac Creek. Most of all I got to talk to somebody for the first time in three days. Nice people. I wished them well.

Then I missed the turn to Southesk camp. The sign isn’t visible, at all, from the west, and the turn is easily missed through the general destruction. I hiked on nearly a quarter of a mile before seeing what sure looked like (and was) the campsite and its pond behind me and to my right, going “hey, wait a minute,” and doubling back.

It was worth the trouble to reach. Southesk campsite is small but pretty. So small there is room for between zero and three tents; everyone gets to pitch up nice and snug in a tiny circle right around the eating area, so close a grizzly could just turn and swipe everyone open without taking a step. The bear hang is taaaaallll, at least (once you find it hanging, safely distant, over the entrance trail).

The unobtrusive little site serves as the foreground for grandeur. Mount Dalhousie and its massif gloriously dominate the skyline behind the still pond that serves as a water source. It is a good pond as ponds go, and very pretty, but the life is visible in it, and I had to hope I hadn’t somehow invisibly broken my water filter. This also makes it a decent site for bugs, not just mosquitos and flies but bees, wasps, ants, and crickets; the little camp area projects into the pond on a mound in a tiny peninsula and is a natural meeting-place. It can be loud, and probably annoying, but I had been blessed with a shortage of bugs on this trip and was blessed again, finding even the increased pressure not much more than a nuisance. My head net and long sleeves stayed in the bag. The scenery’s worth the bother, and the pole-and-a-hole is probably the most overengineered I shall ever see. I loved it.

But what I loved best was that, through some miracle, my improvised half-equipped boot repair had held up perfectly through a rugged, rugged day.

Most visitors call Southesk, with its lack of running water, “peaceful.” There were times in the night when I preferred “creepy.” The sounds of insects, buzzing in my fly, smacking into the tent, making their creep-creep noises outside. A warm, high-altitude wind all night created a moderate ruckus but barely kissed my tent with breeze. It took a while to get to sleep, and my dreams were complicated.

But it didn’t rain, it was very beautiful, and I don’t believe the pond poisoned me, so Southesk is good in my books.

The trail to Isaac Creek, my next stop, is known for two things: blowdown and Isaac Creek. By South Boundary standards this is a pretty reasonable list! Fording Isaac Creek can be tough not only because it’s the highest-volume ford on the trail but because it can be hard to actually find your target across the broad gravel flats of the creek. As a result, rested or not, I was away bright and early to catch the creek eight and a half miles later before it had swollen with an afternoon’s melt. Well, early-ish. 8:30. It would have to do.

Let’s generalize the hike to Isaac Creek into three main types of terrain. The first is “SBT traditional.” Low-lying (I mean, we’re at like 5,000 feet base elevation but relatively low-lying) with willows, berry bushes, and pine trees over the trail, veiling a usually-deep, sometimes overgrown track filled with tree roots and rocks. Even this type of trail is at least clear-ish and not as bad as its equivalent was after La Grace, and of course if there are views, this is where they are.

Second, there is “nice trail.” Forested, soft, pleasant, broad track, usually pine needles underfoot, typically a bit higher-up. Not much to see but great, great walking.

Third, there is “downed trees.” Pain in the butt. I don’t know whether the erstwhile trail maintainers with chainsaws just skip this part, but this is a very good leg for downed timber. I saw a few trees that might have been down for decades but several that definitely weren’t. There is usually room to get around or over the trunks without too much drama; I only had to really duck twice and never had to take my pack off. Unfortunately, and not coincidentally, the otherwise-“nice” trail produced the most deadfall. It’s never too bad, I’ve seen worse on Vancouver Island, and all the worst stretches were over before I could get too tired of them.

That’s your hike. Walking through the forest, negotiating obstacles. It’s the very opposite of the earlier technical challenges. There isn’t even much change in elevation! Nor is there much to look at, save in the willows, though there are moments to see Mount Dalhousie, behind, or Tarpeian Rock, coming up ahead.

At Isaac Creek, one does have to work. The gravel flats from trail to trail are very broad, with the creek well-braided, and the yellow rectangle showing camp at the south bank of the creek is obscured by new growth and hard to find. Fortunately, the area is reasonably cairned. If you see cairns when you’re there, follow a line between the first cairn you see and the yellow marker on the exit (north) side of the trail. There is a second cairn on about the same line; stick to that vector. After passing some mid-river brush, the yellow diamond was visible to me above a row of three cairns. If you don’t see it, err left (to the east). Don’t cross too far to the west, where the bank is forested; the bank you want is stone. There may be footprints in the sand to help give you ideas. I made the compass bearing from marker to marker about 160° SSE.

That’s if you’re going my way, of course; southbound. What about you nobos? Easy: go to the creek, find the marker on the north shore, and walk to it. (It is much more visible in that direction.)

Don’t literally just walk marker to marker, of course, you idiot; ford the creek carefully like an intelligent person. It moves quick; I slapped more Tenacious Tape on my bad boot to keep the scouring water away, took my time picking my line, and wound up with a good one. The channel got no worse than high-knee deep around noon.

Noon. I had left early enough, apparently. That’s an awfully long time at Isaac Creek campsite. Many have liked it but I found it depressing.

It’s a well-constructed old horse-hiker camp. A large, attractive meadow, in front of a forested haven for horses, with old corrals, an interesting layout, and an air of history. I was too late in the year for wildflowers, but the meadow is pretty and has plenty of room for tents. Unfortunately, the previous winter a storm went through and wrecked the place. The old horse corral is in ruins, the bear pole has been destroyed (I believe I found it on the ground), and no good alternatives were obvious18. What on the videos looks like a homey spot with plenty of open space is now a land of downed trees, cleared up to some degree but still plainly not what it was. Somebody forgot her bucket hat drying on a bush.

I stowed my food in my tent and soon found that I was far too self-conscious about leaving an unguarded tent full of food and garbage alone long enough for a side-trip to the warden cabin. It’s not far, but my trash had a distinct aroma when I stored it anything less than perfectly and the many berries on the hike in gave a bear a reason to visit. I hiked up the path to the cabin for probably five minutes, got nervous, and went back. It would have been fine, and if I was worried I could have carried my food with me, but I was tired and monkey-brain instinct ran ahead of reason and curiousity. Instead I did some washing, charged stuff, watched the sky go greyer and greyer, watched my stories, and kept reading my books (ebook readers are a wonder on the trail).