Skagway. I can’t believe I’m back in Skagway.

I have visited three times, which is two more than you should. In 2017, an aborted backpack to Kluane National Park (our river disappeared) turned into a week pottering around anywhere you could bus from Whitehorse. Thus a bus trip to Carcross, the most boring town in the world, and a transfer onto the White Pass and Yukon Route railroad down to Skagway. In my spare time I am a train nerd, and like most western Canadians I’d always nursed a modest, Pierre Berton-level interest in the Klondike Gold Rush, a grand tale of human irrationality, hubris, greed, glory, triumph, and despair. Skagway was one of the main Gold Rush towns, these days preserved almost as a memorial, and the railway had been built to convey prospectors and equipment through the early days of modern mechanical mining.

En route the train stopped at Bennett, British Columbia, the near-ghost town that is the northern terminus of the Chilkoot Trail1. From the station you can see a sign for the Chilkoot Trail National Historic Site of Canada. Saint Andrews Church, a rare surviving Gold Rush-era building, looms between the mountains above. You get off the train with the other tourists and ramble briefly around Bennett, looking at the interpretive signs and enjoying the scenery. It is extremely pretty. Some people camp there for a night or two and take the train back without hiking, and you see why.

Then you get back aboard and ride to Skagway through the White Pass, which is stunning. I swore, on that train in 2017, that I would someday hike the Chilkoot, the 33-mile route from sea level by the Taiya River, through the kilometer-high Chilkoot Pass, and back down to Bennett, where Gold Rush prospectors took to their boats and the hiker to his train.

Skagway sucks. It’s a cruise ship town, selling excursions, fashionable semi-precious stones, and art you’d be ashamed to display in your eccentric aunt’s disused nursery. The residents are A+, there are two breweries, and the scenery could make you cry, but cruise ship passengers crowding the sidewalks, blocking traffic for iPad selfies, and acting like the world is arranged for their benefit run it all. I’m sure most cruise ship passengers are lovely but in Skagway they hide. The train ride, for example, vandalizes the views with a person on the tannoy for 67.5 miles giving colour commentary that Enid can tell Margey all about at bridge club. I couldn’t have been happier to leave, even though it meant stopping in Carcross again.

I returned the next year, though, on the Alaska State Ferry from Bellingham and planning, at first, to backpack the Chilkoot. If you can afford the time, and they don’t happen to be on strike, this is the only way for a backpacker to travel. A stately four-day cruise up the Inside Passage, no mess, no frills, just good people, surprisingly good vittles, undrinkable wine (oh well), and the best backdrop to be seen from a public highway, on display dawn, day, and dusk. The backpacker can save a fortune on a stateroom and pitch his tent on the deck2, or sack out with his sleeping bag in one of the lounges. I found the trip wonderful, but as to the hike life had intervened and I settled for a one-night out-and-back trip up the least handsome part of the trail to Canyon City before fleeing to Whitehorse by bus.

Song Inexplicably Stuck in My Head All Day: “She Talks to Angels” and “Hard to Handle” by the Black Crowes. Not appropriate to the surroundings and not even approximately good songs, these were a burden heavier than any camping chair.

Now it was 2019 and I was making a flying visit. After work in Vancouver, BC on Friday, take Amtrak to Seattle and reach the airport around 11:30 PM. Nap on the benches at SeaTac, then the dawn Alaska Airlines flight to Juneau. A small plane and a 45-minute flight to Skagway3. Sprint around the obnoxiously-familiar townsite collecting stove gas4, train ticket5, and souvenir for back home. Then I rolled up to the United States National Parks Service’s Chilkoot Trail office, between three bad art shops and near the ice cream, for a mandatory trail briefing.

Organizationally, the Chilkoot has much in common with the West Coast Trail. Both are popular and limit the number of hikers permitted every day. As a result, it is wise in both cases to book in advance. Both also subject you to a mandatory orientation, to talk you out of being a danger to yourself and others.

The Chilkoot’s orientation is better. It is more convenient, running every two hours from 8 AM to 4 PM in peak season. While the West Coast Trail orientation seemed mostly to be about burger joints and tsunami safety, the Chilkoot one was presented by Rain, whose style is accurately given by a video on the US park website. She’s a fine raconteuse with plenty of useful information. There isn’t much tsunami risk on the Chilkoot and no burger joints. On the other hand, there’s no point listing recent bear sightings since the answer is “fucking everywhere”6 so she is very serious about bear safety, very serious about caching everything that might imaginably attract a bear into the bear boxes first thing when you arrive in camp, very serious about never leaving packs with odorants in them unattended, and very serious about strictly preparing and consuming food and drink in the designated cooking areas. It’s a serious subject. You hear about dumb tourists deliberately feeding bears, and if the Chilkoot got that habit rangers would need to start carrying machine guns.

There’s also paperwork, since you’re hiking across an international border7, and a bit of politics. The Americans who patrol national parks are called “rangers,” the Canadians are “wardens;” one group Tolkien, the other group Bioware. This leads to sentences like “at Sheep Camp the ranger will tell you to start early, but if you reach the Pass too late the warden might let you stay over,” which takes a little bit of keeping-straight.

With paperwork but without optional bear video the orientation took about 45 minutes and was informative. But it’s Skagway, so you get the cruise ship passengers coming off the street into some point of particular importance to gawk and ask stupid questions like this was all part of the show. “Oh how far is it? Five days?! Do you bring a tent?” They possess supernatural powers of inanity and distraction. Are people sent on Alaska cruises by relatives who need them far away, preferably in a place with bears? “Where do you get food?” From your corpse if you don’t fuck off.

The trail actually starts not in Skagway but near Dyea, a Gold Rush rival turned ghost town and government campground8. You can drive the gravel road or hike nine miles of narrow, car-filled dust, but the best bet is to drop US$20 cash on Ann Moore’s trail shuttle. She or her husband will have you put your backpack in a wagon, pile you into a van, and give you a ride. They’re a hiker-focused service, their schedule matches the orientations, and they’re typical friendly Alaskans who shoot the best kind of breeze, talking about nature and 80-year-olds who hiked the trail and 3-year-olds who supposedly did, though they suspect dad helped a bit. Hearing I was from Canada, the driver was sure to point out a couple bald eagles swooping over the Taiya River delta. I didn’t have the heart to tell him that in the Lower Mainland and the Southern Gulf Islands bald eagles are somewhat more common than turn signals.

Just before the bridge into Dyea proper, you’re dropped at a parking lot with outhouses and benches. Shoulder your packs, adjust straps, take a photo in front of the park sign of the group of pleasant, chatty women in the van9. Gird your loins.

Then start hiking. It begins with Missionary Hill, so-called, we are told, because if you do it without swearing you must be a priest. It is not severe: 300 feet up, 300 feet down, mostly good surface with brief looseness. It is the best-trafficked part of the trail, with locals and guided groups doing day hikes, and on the Chilkoot elevation map it looks like one of those mythical Russian railways where the czar let his fingers hang over the ruler as he tried to draw a straight line and the engineers had to build these random curves. Compared to what lies ahead it is contemptible. But it is right at the beginning, almost the very first steps you take, and the river-rafters and day-trippers with bare backs move ever-so-lightly, your pack will get no heavier, the views are nil, and you know that it’s relatively insignificant to what comes ahead.

The trail softens soon. All the way to Finnegan’s Point, the first campsite, it feels like a road10. You cross stagnant beaver ponds created by non-native animals who in the 1990s re-engineered this section of trail, building a network of dams that killed a few acres of trees without regard for the backpackers and park rangers who had traditionally used this area. But man has adapted, building handsome new, though sometimes not-nailed-down, boardwalk over the length of the pond.

Here the trees finally open up enough to allow glimpses of the Irene Glacier and some mountains. Brief but welcome, though you’re still so close to sea level that it towers over you. The river is accessible most of the way, but the glacial water is filter-murderingly silty; take water from side streams when you can. Some of those streams have remarkable salmon runs that can be seen from the surface, and one bridge four miles in was out because twelve people stood on it staring until it broke beneath them.

My first day went past Finnegan’s Point, an agreeable and quiet camp for those starting late and going slow, and nearly three miles on to Canyon City. On this leg you are oh-so-gently reminded that you mean to climb into the alpine, like the butler whispering into your ear that your bath has been drawn. You rise, a little, with a net gain exceeding 300 feet, and the path grows narrower and rockier (thanks, it is said, to a winter storm years ago that battered the trees down). It is moderate by comparison to the easy trail earlier, and the chief hazard is fatigue from whatever long day brought you to the trailhead.

Canyon City is so-named because it is in a canyon and during the Gold Rush there was a city there. You can cross a sketchy suspension bridge and walk a mile-long trail to see its ruins, a boiler. Otherwise it is a popular, loud camp. Those two adjectives are not related: it’s popular because for those going a modest pace it makes an obvious first night’s halt, and it’s loud because the Taiya River rushes through the titular canyon at speed, roaring fit to fill your ears at all hours even though good tree cover bars the wind. The campers themselves were a quiet, respectful bunch, give-or-take the kuh-rang of a bear locker.

The park has begun installing tent platforms at Canyon City. Most campgrounds on the Chilkoot Trail have platforms, meaning the wise tenter will bring plenty of extra line for his stakeouts and be prepared to tie them off. But in the summer of 2019 Canyon City’s were unusually obnoxious, lacking good tie points and in some cases being only half-finished. One late-arriving group carried boards from one construction site to another, adding them up into something approaching usability. There were still ground sites available, but the platforms are clearly where the future is headed; they’re easier on the ground and in the rain are much appreciated regardless of the momentary inconvenience pitching camp.

I arrived tired more in spirit than in body; I’d had a long couple days with not much sleep, and had foolishly left my girlfriend’s brand new camping mug, which she had kindly lent me, three and a half miles back by the river. Despite a successful day’s hiking I found myself irrationally demoralized, but bucked up because of something I normally hate. Had I the power I’d give all vandals a rope, and it’s a pretty common name, but seeing “Ben M.” carved on one of the campground’s bridges gave me the feeling that I was meant to be here after all.

Song Inexplicably Stuck in My Head All Day: Al Stewart’s “Year of the Cat.” A jazzy tune about bohemian living that could not be less in tune with the surroundings, but a good song.

A magnificently restful night, a satisfying breakfast of apple cinnamon quinoa, tea drunk straight from the pot, a black bear jogging through the cooking area in front of ten people, a fine start to the morning.

I am forming the impression that the Alaskan woods are bear country. Tracks abound, and one lucky camper awoke to a steaming fresh pile of bear scat in front of his tent, which I guess answers that question.

Day two was planned to be short. If I hiked the Chilkoot again, I’d damn the torpedoes and go straight from the trailhead to Sheep Camp in a day; it would be a grind but I’d feel good having done it11. On the other hand, it would have brought me into Sheep Camp around 9 PM, missing the daily ranger briefing on conditions over the Chilkoot Pass, and before a 4 AM wakeup call to summit in the best part of the day. Having gone to work, napped at an airport, flown into Alaska, and hit the trailhead, there’s something to be said for conservatism. Also, on the Chilkoot Trail you need to book your campsites in advance. I booked mine the previous November, when to say the least I did not know what the weather would be. What if it had been miserable?

The summit is the Chilkoot Trail’s main feature. The quota system is based on the number of people crossing the pass each day. Your trail permit shows “Summit Day” as about the most important thing to know. 7 PM daily at Sheep Camp, a ranger briefs you on the pass’s current conditions. In the pass itself, a warden keeps watch from his patrol cabin, guarding hikers too weary or late-starting to cross the 7.8 miles from Sheep Camp to Happy Camp in a day. Nobody bothers to write much about walking between Dyea and Sheep Camp, but once you’re on the Chilkoot Pass you’re in among history: the Scales, the Golden Stairs. The pass is the show. It’s not too tall, not too long, but it can hurt you, especially if the weather is bad. First-timers should err towards showing it more respect rather than less.

If you, like me, take a short second day, it starts at its toughest. There is an interpretive sign not far from Canyon City that begins “Difficult Trail Ahead.” “Oh dear,” says the innocent reader. It’s not that bad, but you have work to do, ascending out of Canyon City’s canyon by a long, windy, rough-hewn stone staircase. One party I talked to met a bear cub there, which must have been fun. It is broken, gradual ascent, two steps up and one step down, with good patches of bear-friendly, shoulder-high bush to pass through, and it’s a drain.

Dry, too. Once up the stairs there was no water at all for two miles. This was a dry season; you can see the channels where water would normally flow. Most of the time you’ll hear the river but it’ll be to your left and way below you. It’s worth carrying a bottle.

It was a cloudy morning, perfect temperatures, a few views mostly hidden, and I flew to Pleasant Camp. The trail was no worse than a healthy intermediate in the conditions. Even rain I think would mean only mud and watching your footing. The worst part was another sketchy suspension bridge.

The original location of Pleasant Camp, beneath the trees on a short sandy beach, is marked by a sign and earns its name. But today campers stay another quarter-mile up the trail in a pretty generic woodlot. Only a tributary of the Taiya passes here, so it’s quieter, and its awkward location means fewer campers stop, but I sure didn’t leave wishing I could stay.

From there, enjoy the stroll to Sheep Camp. It trends up hill but so slightly that, knowing Sheep Camp was above Pleasant, I was worried that I was about to walk into some bloody cliff-face just before the campsite. There is very little to say about the hike: it is a walk through the woods. With the clouds out there wasn’t much to look at, and most hikers have done something like this a million times.

Great bear country, of course. Nearing Sheep Camp, I was taking a swig from my canteen when I heard a great bang and choked on the last gulp.

“Hello?” Only the sound of steps replied.

“Nobody here but us humans,” I said in my most reassuring voice, advancing cautiously around the next kink in the trail, whereupon I saw the US ranger cabin and the ranger himself, backpack shouldered and locked in the zone, off to start climbing the Chilkoot Pass at 10 AM, sweep up stragglers, and get material for his talk.

Apart from the ranger I was the first camper to stay at Sheep Camp that day, and he lives down the street so he doesn’t count. In the cloud it is sort of ugly and bugs like it. In the afternoon they blew off and revealed a camp seemingly hemmed in on three sides by swift-rising mountains, but trees are thick enough that you don’t get much grandeur and the view is contemplative rather than spectacular. Pretty enough, and I enjoyed it when I could do my writing in the picnic shelter away from the insects. It’s not a large area, given the horde of campers depending on it, and the size of the main cooking shelter, the second- or third-largest structure on the trail, shows early arrivals how popular Sheep will be.

But American ingenuity provides. The campsites are on wooden pads, older and better than those at Canyon City with plenty of convenient tie-off points. The paths snake up the hill and through the bush, not only housing the multitude but lending privacy to most. In the evening a woman I’d oriented with, after looking around the camp in despair, was reduced to asking if I’d share my tent pad, but the time I’d moved my tent off to the side her partner had found that there was an entire wing of vacant spots past the outhouses. The big shelter is positively first-rate and the newer warming cabin not only looks amazing, it smells amazing.

The ranger, whose name turned out to be Peter, returned from the summit around five and at seven gave an interesting twenty-minute talk. He had a charismatic aspect, movie-star looks, and useful information, which is a good package. He asked who had seen a bear today; every man-jack of 30 people had. He handed out long, full-page American federal government forms to be filled out for every individual sighting of every individual bear. I for one decided I hadn’t seen a bear after all.

He also had current intelligence and sensible advice. Four people in two parties were camped at the summit as we spoke, a dramatic but desolate, lousy spot to spend a night, because they’d made too poor time to do the second half of the day’s trip to Happy Camp. Patiently, he explained the dramatic progress of the route, how you’d start uphill almost from the first step of tomorrow’s hike, ascending through forest and sub-alpine to the Scales, the last chance to rest and water before Canada. Then the crawl up the famous Golden Stairs, a huge field of huge boulders stacked atop each other to an infinite depth, striving towards a niche in the mountains, reaching it at last, and… it’s a false summit. Pushing up further, one eventually sees an obelisk honouring the history of the trail and marking the formal international border, and… it’s a false summit. Finally, after even more up, one reaches the Chilkoot Pass warden cabin and tiny warming hut, and there, at last, you have reached the top of your world.

Get an early start, he advised: it was likely to be a long day, with fit men carrying light packs reaching Happy Camp in five to six hours but the average time being eight to twelve, and the forecast was for clear skies. A clear day on the Chilkoot Pass is a rare treat, but both the ascent and the descent are over miles of bare, unsheltered rock, and with the sun at its full intensity it would be brutal out there by mid-afternoon. And don’t take a break on the Golden Stairs. Rest begets rest, in his experience: each stop grows longer, the period between them grows shorter, and before you know it you’ve run out of time. A slow, but steady plod up the boulders is far better than a series of rushes and stops. But if you’ve come this far, he reassured us, you could finish.

Now Peter said those of us who would leave could, and gave us a general lecture on the Gold Rush migration as seen by an outdoorsman. He was full of information about routes, passes, watersheds, and natural history. A few people did retire before this part of his talk, but I don’t think those who stayed regretted it for it was very interesting stuff, and if given the opportunity I suggest you stay and learn.

With the presentation done by quarter to eight, most of us were away quickly to do our night’s business and get ready for a heck of a wake-up call.

Song Inexplicably Stuck in My Head All Day: “Don’t Answer Me” by the Alan Parsons Project. Ironic, since when you hear a strange sound on the Chilkoot Trail you absolutely want it to answer you.

4:00 alarm. Bah. Roll out from under sleeping bag, worn open as a blanket. Fresh socks from tight-packed dry bag. Even in Alaska in August there’s not enough light to work by at 4 AM so on goes the lantern. Some have gotten up even earlier than this and the bob of headlamps is visible outside. Slice off a piece of moleskin (young sheet blister on the bottom of my left foot; far from serious but who needs it). Pack pack pack. Depressingly slow. I hit the food lockers only at 4:40 and am nowhere near the front of the peloton, squeezing into a spare corner of picnic table.

Breakfast (the good one, peanut butter and raisin oatmeal). Half a pot of tea. I eat at 5, when I’d hoped to be leaving. Still early enough but there are already keener folks than me on their way up the pass.

Over moderate distances I am a very quick, actually stupid quick, hiker under most conditions. But I expected to be caught in a jam on the ascent up the pass. My boulder-climbing work has been done in Vancouver, for example on the Hanes Valley route, and people who I’d blow by on the straight and level would be my constant companions climbing the boulder field to the Crown Mountain col. This didn’t wind up happening today. My theory is that Vancouver hikers who’d attempt the Hanes Valley have a much more homogeneous fitness level than those who find themselves on the Chilkoot, and some people get very unpleasant surprises. Especially on days like tihs.

They aren’t kidding when they say you start ascending right out of Sheep Camp. You cross a bridge over a tributary of the Taiya, begin going up, and give-or-take a couple false summits don’t stop until you’re in Canada. It’s a fairly serious ascent through the forest, and gradually the tree cover disappears. More and more often, dirt gives way to boulder and stones. Even at 6 AM in a dry August there was water everywhere, though I’d hate to be a late starter (or a ranger) doing it in the blazing sun. At this point it is still a trail.

Relatively soon, you get your first real look at the Chilkoot Pass, obnoxiously far up. But there are compensations: after two days of middling forest mystery the views are opening up, as you ascend through sub-alpine and into proper mountain terrain.

The last reliable water before Canada is at the Scales, the famous Gold Rush site where loads were re-weighed (and, if you were using professional porters, the prices went up) for the push over the pass. Today the name is strictly historical, the literal scales long gone, but you’ll recognize them because a sign will tell you so. Though very stony, the Scales are easy enough walking for fresh legs and it would be an agreeable spot to rest and refuel for the major ascent if not for the mosquitoes.

Mosquitoes, I’m afraid, played a growing part in my day. I’d picked up a few bites since Dyea but nothing worth writing home about, until the Scales. You cross the Taiya River here for the last time, and what at Dyea was a great rushing torrent is here braided and, at the time of my visit, barely boot-sole deep at the surface. But it runs mostly beneath the boulders you walk on top of, audible far beneath your steps, inaccessible to you and me but for mosquitoes the very idea of heaven. They come up through gaps in the boulders by the squadron, harrying passers-by and assaulting those unfortunate enough to stand still until they go mad. It was an effort of will to stay long enough to filter and drink 24-odd ounces of water, but I stuck it out—and not long later was very glad I did.

Inexplicably, there seems to be some confusion about the Golden Stairs. The main movement of the Gold Rush was during the winter, and enterprising souls carved literal stairs in the ice and tried to charge for their use. There are frequently-reproduced photos of a long, uninterrupted black stripe of would-be prospectors between the white fields of snow, trudging up the Stairs carrying the famous ton of supplies 50 pounds at a time. This, again, was in winter. In the summer there is usually no snow or ice on the Pass. And yet I, personally, met people who expected a literal staircase to the summit, that hand-carved ice steps might somehow still be there in the middle of August 120 years later.

It’s not a staircase. It’s a boulder climb. A simple enough boulder climb, on a day with any visibility, a mile long and half a mile up. The route is marked with tall orange poles that should guide you in anything but the foggiest conditions, though very foggy days do happen. My day was splendidly clear, the way was easy to follow the whole way, and it could not have been better.

Even an easy mountaineering route is still a pain. Climbing boulders is hard, ascending a steady 45-degree slope is hard, doing both at once with a full backpack is a proper workout. Add in your knowledge that the summit you see above you is false and the 3.5 miles from the summit to Happy Camp are said to be as difficult as the ascent, and there’s a good deal of apprehension to go with it. I am sure that people without boulder-field experience underestimate it. If you plan to do the Chilkoot, and have the option in your neighbourhood, why not day hike one of your local boulder-field ascents and see what it’s like?

But it isn’t technical and boulder-hopping is a skill most people develop surprisingly quickly. In my estimation the Golden Stairs are both shorter than and step-for-step easier than the Hanes Valley boulder field, except of course that in the Hanes Valley you aren’t carrying a stonking great hiking backpack and I’ve never once lost all my water.

About a quarter of the way up the Golden Stairs I was bending way over to use my hands for balance on some teetering boulder. Too far; my only, and completely full, water bottle fell out of its sleeve on my backpack, bounced off a rock, and fell straight down a chasm where it will probably stay until the world is remade. Forget getting it out; even with a light I couldn’t so much as see it, and it hadn’t bounced more than a foot horizontally.

I had three rather quick thoughts. The first was that, between this and the mug, it had been a rough trip for drinkware. Second, drinking my fill at the Scales had been worth every drop of blood the mosquitoes had billed me. Third, I was really glad that I used a Sawyer Squeeze water filter, because the Sawyer uses plastic bags to hold the untreated water you then squeeze into a drinking vessel/your mouth, meaning that I could still transport water. But the bags, which are a hassle to hike with full, were empty now, and the ascent would be finished dry.

I tried to make up for it by drinking scenery instead. The further up you go, the more attractive it is looking back, and stone slopes encourage you to stop a step and look behind you once in a while. I couldn’t recognize distant trail or even anything as far as Sheep Camp, which since you can’t see the Pass from there isn’t too surprising, but it was pretty, and gave the impression of real progress. I felt very blessed to have such a clear day.

After much grunt work, more sweat than a teenage boy in the girls’ locker room, and a distinct impediment in my sock as the moleskin patch worked itself off, I reached the first false summit. Blearily, through my fogging spectacles, I looked behind me on the best view of the trip so far, a glorious panorama of Alaska through a notch in the rock, then looked forward to see a quintet of fast-moving women I’d met at the Scales going at a hell of a clip over seemingly-flat ground and thought “maybe this won’t be so bad.”

Obviously there was still plenty of boulder climbing yet to do but it wasn’t. The first false summit means the worst of the ascent is over; you’re in the swing of things now and have done most of the distance. The valleys between the false summits are blasted nightmares of broken rock that make finding the best route an exercise in patience, and you need preternatural stone sense to invariably find the best way forward. But, relatively soon, you’re standing on the second false summit, looking up at a cairn honouring the Gold Rush pioneers and incidentally the international border. The route markers change from the American-style orange poles to Canadian orange flags on unmarked steel poles. There’s arguably a third false summit but it’s more a little mini-bump, you won’t be fooled by it for a moment, and I got so confident that when I saw a crummy-looking, pestilent rainwater pond I passed it up; thirsty though I was, I knew there was better not far ahead. By 8 AM I was standing beneath a fluttering maple leaf atop Chilkoot Pass.

It was a remarkable place to be. A healthy pool slaked my thirst and filled my bag. I stood in the tiny warming shelter12, filled out a postcard to myself13, and talked to one of the parties who’d spent the night at the summit. I spent a few minutes wandering with my pack off, adoring the view, easing my shoulders, and then was off.

The Canadian Chilkoot Trail website says:

Many are surprised when the trip from the Pass to Happy Camp takes as long and proves just as challenging as the climb from Sheep Camp to the Pass. Snowfields between the Scales and Happy Camp persist throughout the summer months. Be prepared to camp on snow at Happy Camp until late June/early July.

It took me about three hours to get up and about two to get down. And the way down was not free of challenge at all. There is a lot of walking over, and balancing on, huge boulders, broad and flat like prehistoric sidewalks upheaved by earthquake. There was an unsafe-looking snowfield which you could either walk over, risking a ten-foot fall when the huge, rotting overhang inevitably broke through, or (my choice) awkwardly side-step along a steep slope of loose stone to pass it. The surface was often hard, and it wound up and down, and as the day advanced on the treeless trail the heat grew uncomfortable. On the bright side the work felt a lot less dangerous, you used your hands a lot less, and the views were beyond spectacular.

Crossing into Canada is like flipping a switch. One moment, American coastal rainforest, the next the alpine near-tundra of Canada’s near north, stunted lodgepole pine and and wildflowers, birds and butterflies. The glacial tarns shine cerulean in the sunlight, still and reflective as polished glass, and as you wind through the mountains it feels like every fifteen minutes the view has changed to something distinctive and equally remarkable. I had to stop taking photos so I could actually hike. It may have been more spectacular than my fourth day on the West Coast Trail, which I would have thought was the most beauty a man could see and live.

I didn’t find the way down as hard as the way up, but the obnoxious stone and persistent tricky bits eroded my patience. There’s a sign beside the trail at the appropriate point which says “Happy Camp 2mi,” and everybody I talked to agreed that we greeted that sign with shock. “Still that far?!” The heat was coming on fast, beating off the rocks, and if I was hiking past noon I’d regret it. Though the scenery is open, Happy Camp itself is well-hidden in a copse of trees, and I was almost upon it before I discerned the roof of the cooking shelter through the pine. But I made it, just over five hours after I set out. Because my GPS watch automatically switched from Alaska to Pacific time when I crossed the border I thought I’d done it in six and was very happy. When I looked more closely and saw my actual time, well, I felt pretty proud to be a fat man carrying a hiking chair.

Happy Camp is tight, crowded, and public, and I picked out the best platform for myself. The setting among the squat trees is pleasant, though exposed to weather, and the creek a short slope below is perfect. It’s a very fine place to spend an evening, if the weather co-operates. The interpretive signs suggest some gold rushers viewed the name as an ironic joke, and I’m sure that on a lousy day, or if I’d done the trail regularly and had a host of memories, Happy Camp might not be my favourite. But for me it was well-named, mostly.

If you want something new to feel anxious about, try being a fast hiker on a difficult trail knowing that people, who you have barely met and are in no way responsible for, are going slow behind you in potential heat stroke conditions. I was the first to get to Happy Camp that morning apart from a German ass-hauler who I never met but always saw in the trail registers ahead of me, and just ahead of the five women who I’d leap-frogged with most of the morning (they were faster than me really; while I could burn myself out getting to Happy Camp they were going to Lindeman, and I am unembarrassed to accept third place on the day). But there was a long, long period of solitude after they left. People trickled in through the afternoon, red-faced and ruined-looking by the heat, with no thought beyond getting into the creek to cool off. Some of the valleys after the Pass felt like a convection oven, with merciless heat radiating from all sides. Most of the slow-goers on this sunny day preferred the climb to anything else, and the only exceptions were me, who finished early, and a party that included a woman who was only 5’0″ and struggled mightily getting up some of those boulders. No doubt, such ascents are a tall man’s game.

Helpfully, if there is a crisis, Parks Canada posts the location of the nearest telephone in each shelter, as there is no cell service at all between Skagway and Carcross. Unhelpfully, the nearest telephone is at the border crossing in Fraser, which is literally across a mountain range from you; it would be ten times easier to hike to Lindeman or Chilkoot Pass and find a warden with a radio.

Meanwhile Happy Camp filled up; by 6:30 the last faces I’d remembered from Sheep were pitching their tents in a bustling camp that had nothing in common with the desolation I’d arrived to. The best line of the day went to a teenager who I’d hardly heard five words from in the previous two days, coming into camp with his guardians and saying “is there a Subway here?” in tones of weary but undisguised triumph. Happy indeed.

Song Inexplicably Stuck in My Head All Day: none; it was rather a high-event day.

Probably my most important job in the morning was to get up and look at where I was.

Happy Camp is intimate. When someone in one tent turns over, five tents hear it. It can’t be helped, and as a compulsive tosser-and-turner with an infamously crinkly sleeping pad I wouldn’t criticize even if I could, but it’s a fact and a bother if you’re already sleeping light. And with thirty mosquito bites playing me up I was sleeping pretty light.

So at about seven I got up and looked outside, and it was amazing. The company was friendly, the food bag was getting agreeably light, it had rained overnight but was clear now, and a hard-to-improve-upon hiking day beckoned.

The social element of the Chilkoot Trail was unexpected. By preference I usually hike alone, as I did here, and loneliness is an occupational hazard. Sure, when backpacking I talk to other people, but soon we go our separate ways. The Chilkoot was unusual in that, while I hiked by myself, at camp I would often enough find myself with one group or another into the evening, joining card games, getting in on jokes, and being positively sociable. The West Coast Trail certainly wasn’t like this. I think it’s a combination of the regularly-spaced campgrounds meaning that even very different hikers wind up with similar itineraries, the mandatory communal cooking areas giving companionship to anybody so inclined, and the native friendliness of the many Alaskans and BC interior-ites on the trail. Hiking life is, in general, much friendlier than civilian life, but the Chilkoot was a step up from that. You hear about people on the Pacific Crest and Appalachian Trails picking up with total strangers and spending hundreds of miles in intimacy, and had always suspected that if I ever get to do one of those great trails I’d be an exception. I’m no longer so sure.

I had a leisurely breakfast in good company and struck out, compared to yesterday, almost decadently late. This being the Chilkoot Trail you begin with a sharp ascent. After carefully stepping along a narrow rock path away from Happy Camp, you take switchbacks up from near water level to the ridge overlooking Long Lake. It’s not a contemptible climb up the rocks, but unlike yesterday these are small stones in secure ground; sharp buggers but easy enough. In the sun the work made me sweat, and at the wrong time of morning the sun was in my eyes, but I felt fresh and was used to worse.

The “ridge walk” is quite low compared to the mountain ridges either side of you but offers fine views of handsome Long Lake, so named because it is long. After a mile and a half of that you descend much more gradually on a path that’s mixed dirt and snow between the stones, just nuts to a Vancouver North Shore hiker like me. Cross a steel bridge, which should inspire the American trail with its stability, and arrive at Deep Lake campground.

I can see why rangers and wardens like this place. It’s sleepy, handsome, spread-out. Being on the opposite side of the stream makes it significantly more sheltered than Happy Camp though you have hardly lost any altitude. Happy Camp is much more dramatic than Deep Lake, and on a clear day prettier, but Deep Lake would be more peaceful, murder you less in a storm, and doubtless dodge some crowds.

Deep Lake is so called because it is deep; for a group that included Robert Service and Jack London the stampeders seemed to lack creativity sometimes. From the campsite you proceed along pleasant track while beside you the lake plunges into a perilous gorge, called the Deep Lake Gorge.

At times the path running by the gorge is narrow and you’ll want to watch your footing, lest you fall off a cliff on one of the easier parts of trail and get in a “World’s Lamest Backpacking Deaths” video. It is also dry, without so much as a pond or trickle accessible all the way from Deep Lake to Lindeman. Luckily I had done my camel act before reaching Deep Lake and made the distance with room to spare.

This was apparently a day for Parks Canada to earn their money. A helicopter bag full of supplies had been waiting at Deep Lake, choppers zipped to and from the campsites for much of the day, and on my way out I passed two wardens whereupon, proving I was back in Canada, each of us stepped off the trail simultaneously to let the other go by.

I had a similar experience with a black bear. For all the bears I’ve seen in the wild before this was the first time I’d actually just run into one on the trail. I am very large, make a lot of noise, and when hiking smell awful; bears tend to fear me. This one was used to worse.

It was not a dramatic encounter. He stood and faced me, ears up. I tipped my cap and wished him good morning, asking how he did. After some appraisal he turned and left, which was kind since we were on a slope and I saw no obvious detour. I waited five minutes then resumed hiking, speaking my inner monologue loudly for about a mile, and saw him no more. A gentlemanly bear. I regret to say, since this diary is honest, that while he was sitting up I took a picture with my phone like a damned tourist, but serves me right: it wasn’t very good.

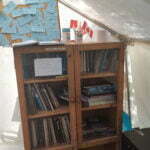

Lindeman Lake is really two campgrounds separated by a five-minute walk. The lower campground is prettier, closer to Bennett, and has sights like the Parks Canada summer headquarters and an interpretive tent featuring the Lindeman City Library, interesting Gold Rush-era photos and documents, bear reports14, and your trail completion certificate15. It was also closed for camping due to bear activity. The upper campground offers views that I’d call spectacular if I didn’t compare them to the lower, a sediment-filled lake with no accessible moving water, rusticity, and a maze-like layout that you can easily get lost in. I camped there, because I had to.

Here, many people I’d been sharing shelters with for days visited and pushed on, heading for Bare Loon Lake to shorten a final push to the train. For those heading back to Skagway, the train leaves at 3 PM Alaska time, making for a perfectly reasonable final day. But I was going on to Whitehorse, and the train to Carcross leaves north at 11 AM Alaska time; that seemed like pushing my luck, so I decided to stop at Lindeman and spend a final night at Bennett itself before boarding the train at leisure. Once again my schedule had been overly conservative. I’d thought Lindeman might be interesting, and it was, but you didn’t need more than a couple hours. The parks headquarters was shut up behind a bear-proof electric fence, and with plenty of helicopter traffic as the Canadians emptied their outhouses the wardens here did no visiting. The old Gold Rush-era cemetery up the hill is solemn, mostly broken-down and unmaintained apart from the new stone marker of a single Freemason, but small. The weather was getting foul. I could easily have been off the trail a day earlier if I hadn’t been so silly.

Eventually I got company. The rain came in and we crowded under the awning of the small shelter, swapping tales and jokes. I happened to be the only Canadian under the shelter that day, and as will often happen with Americans the conversation turned to how much French I knew; I briefly amused the party by reading the French on food packets and maps. The rain came, went, came back, and turned torrential. Soon some campers were fishing sodden sleeping bags out of soaked tents. Lindeman, almost uniquely on the trail, has no tent platforms, and it figures that it was here that a deluge hit; there was soon a pool inches deep beneath my tent vestibule and others on the corners. Though the contents were still dry they soon wouldn’t be, so I grabbed my poop trowel and dug some diverting canals. This had now become a Leave a Pretty Moderate Trace expedition but the pools drained and the inside of my tent remained bone dry. My compliments to the designers of the MSR Hubba NX, which for a lightweight three-season tent had held up to wind and rain flawlessly.

Luckily the downpour didn’t last, once-veiled glaciers came back into view through the clouds, and we realized we’d seen the worst. We’d been lucky, most of us. At 7:30 a pack of Francophone Scouts from Ottawa rolled up. It had only been sprinkling and, mercifully, the rain paused soon after they arrived, so they were able to get their bomb-proof alpine tents up in security. But they were cold and wet from their hike and accepted space in the shelter eagerly. This was a real flying tour: they’d done a short hike at Kluane National Park, bused-and-trained in to Bennett for a two-night taste of the Chilkoot, and were next off to Dawson City to do a tourism. An ambitious itinerary but at their age I’d been on a school trip to Ottawa, and this was better. Alas, my earlier claims of bilingualism were shown up by these children alternating between rapid-fire French and perfect English at will, and I rather lost face.

Ah, well. I was in the woods, the rain was dying down, life could be worse.

Song Inexplicably Stuck in My Head All Day: The Cars’ “Magic” and, for reasons I have forgotten, Gilbert and Sullivan’s “Major-General’s Song.”

No, life could hardly be better.

Having learned my lesson in the past I had closed my previous day’s diary on a cautious note, and was rewarded when I awoke with the tent drier than when I went to sleep. There had been hardly a patter of precipitation in the night, more animal activity than downpour, and when I rose I saw a fine, partly-cloudy morning. The ground had soaked up the water at last and a perfect hiking day beckoned, with all my goods and sleeping bag bone dry in spite of everything.

So thank you God, MSR, and Lindeman.

I rose so late that one party trying to catch the train had already left and the other was saddling up before I started breakfast. Hoping for more precious drying time I refilled my trenches, loitered over my food with the tent up, and finally packed the thing merely soaking instead of pouring wet. The sight of the mud-spatters up the side of my tent body, which had not disturbed my rest in the slightest, confirmed my respect for this tent that had kept me so cozy.

I beat only the Scouts out of camp and set out hoping for an easy lope to Bennett. Alas! the trail offended my sense of narrative by being notably tougher from Lindeman to Lone Loon than from Deep Lake to Lindeman. Not brutal but a greater ascent, starting right out of camp, in a shorter space with more obnoxious sharp rocks. It’s dry from a bridge just before the ridge to Bare Loon two miles later and the descent from the ridge, though short, is sweet. There aren’t even many views, apart from an overlook of Lower Lindeman and the Parks Canada HQ early on; you just gotta do it.

During the Gold Rush, a few brave souls attempted to get from Lindeman Lake to Bennett by boat, through the rapids. One sees their point at first, as this is rough trail to haul a ton of goods over, and given that I saw more fresh-ish bear trees in an hour than in the previous four days grizz is obviously fond of this spot. But then you look at the rapids into Bennett, and hear about the stampeder who lost two complete outfits and shot himself rather than return home a failure, and hiking starts to seem not so bad.

Bare Loon Lake is a neat little spot. It has tent pads, which is a plus, and only an open shelter with no stove to protect you in inclement weather, which is a minus. In yesterday’s squalls it’s an open question whether it or Lindeman would have been more comfortable; those who stayed at one were inclined to vote for the other. But on a reasonable day it’s very cute and I enjoyed my five-minute halt.

From there the hiking is not difficult; rocks and dirt, moderate grade, and an overcast cool day without actual rain is perfect for making up mileage. But between bear anxiety, sore shoulders, and mostly tree-enclosed routes hiding the beauty, I was eager to see signs of Bennett. The first was the sound of a passing train, as here the trail goes within earshot of the WPYR right-of-way for the first time. The second was an in-use trapper’s cabin about a mile and a half out, with a sign on the door inviting visitors to come in provided they lock up after themselves. With my pack on I didn’t even fit through the door so I looked instead; the ceiling must have been five feet high but the dishes gleamed. The cabin belongs to Edna Helm and her family, the only actual inhabitants of the otherwise-ghost town of Bennett, living off the land and trying not to get too trespassed upon by tourists.

I now know I could get from Lindeman to Bennett by Whitehorse train time, since I did it by accident. I came down the sandy hill to Bennett into a mob of fucking cruise shippers. Excursioning, blocking off whole paths for pictures, and nattering like jackasses. It was Civilization with a vengeance. I set up camp and hid before the train left.

Diarizing in the lovely shelter, I was met by one of the Parks Canada wardens, whose name sounded like “Xanax” without the final “x” and quite left me at a loss. We had a chat as she swept out the shelter and she asked why I’d done the Chilkoot; did I have some family connection?

“Because it’s there (and accessible without a car)” is the real answer, but for the sake of conversation I mentioned how I’d long liked the work of Pierre Berton. Instantly her face turned cordially sour.

“Oh, the White man’s history,” she said in a long-suffering tone. But you can say those words in a friendly way to a White man, and she did, and it was no trouble to be friendly back and spar half-heartedly in defense of popular history while she emphasized what you’ll see for yourself walking around Bennett, that the park is at least as interested in what came before the stampeders as what came after.

It’s always a good idea not to fight on the trail. Not long after I was on an insider’s tour with some other hikers led by Xana/Zana and her co-worker Richard, a middle-aged absent-minded professor sort who could forget where he was going but remember several laminated photos of old Bennett in his backpack. We saw a new building in the final stage of construction by the lakeshore, a first-rate cabin with kitchen and hot shower, heated by the sun with water pumped up from the lake. For all the effort that must have gone into building it, the wardens seemed unsure what it was for; it might serve “international visitors” used to a little luxury. Discreet hints failed to produce an invitation to test the shower, and we moved on.

The group went out of “town” for a short hike to a view of the Lindeman Rapids. The trail is not signed, to protect train tourists from mild peril. Though we had Zana/Xana as well as another hiker who’d been here before, Richard led the way and missed the turn while the more knowing women accurately told each other we should turn around. Eventually, at the bottom of a hill, Richard realized the mistake and tramped us back up. It was worth it; the trail is very short but muddy and semi-rugged and best avoided by the cruise ship type. For us, the view of the rapids well repaid the effort, one last beauty spot out of the reach of the day-trippers. Richard said you could sometimes see grayling shooting the rapids, but at the moment the water was too turbulent. We lingered quite a while.

We were told some history and got some conversation. “This is the one year we’re asking the hikers to eat the berries, there’s so many,” said Zana/Xana, soothing some troubled consciences.

After this, and other time-passers, the train returned Skagway-bound. Off poured tourists, and on poured the hikers going to Skagway, in their separate car to keep their offensive odors away from the quality. A few of us staying the night also went, to say goodbye, to watch an NFB documentary on the Yukon river boats, and use to use the legendary Bennett train station plumbing. The station is only open when a train is in, but they have faucets and flush toilets. They also see us coming, with signs saying “please do not brush your teeth,” “please no backpacks in the bathroom,” and many a plea to spare the much-laboured plumbing system.

The survivors adjourned to the shelter for food, cards, and (in one case) very tiny scrawl in a fast-diminishing notebook. The Scouts arrived just before dinner, no deluge this time. We played a bastardized version of Rook with half-remembered rules beneath my camp lantern; it’s a child’s game, but it takes strategy and luck and the eponymous Team Ben had neither, until at 9 PM I finally called an end to the death march and went out to see a lovely red sunset.

The next morning the Francophone Scouts, myself, and one other boarded the WPYR northbound to Carcross at 10:38 sharp. The sun gleamed across Lake Bennett, improving it immeasurably. A cruise shippist waltzed up the hill from the national landmark entrance, found the first photo spot, and whipped out his selfie stick without turning around or removing his sunglasses. By heroic effort I resist the urge to hit him.

As the train rolled out, the tour guide got on the intercom. “Okay,” she declaimed. “I’ll tell you all about here again, just to drive it home.”

Back to civilization.

- Fun fact: the Chilkoot Trail is listed on every guide of Yukon Territory hiking. It is a relic of the Klondike Gold Rush, which quite literally put the Yukon on the map and anchors its thriving tourism industry to this day. Not a single step, not one foot, of the Chilkoot Trail is in the Yukon: it goes from Alaska to almost the very northwest corner of British Columbia.

- But bring plenty of duct tape. It gets windy on the high seas, and pegging your tent out on a ship’s steel deck is impractical without a plasma torch.

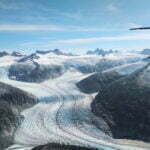

- Via Alaska Seaplanes, who operate scheduled service between Juneau and many ports, including Skagway. Despite the name we flew in a seven-seat land-based Cessna, and with the weather clear we were able to fly between the passes in our tiny plane, way below the mountaintops, so close to the colossal glaciers I could have reached out and made a snowball, then suddenly turning left to rip down the White Pass and thump onto the runway that runs about the length of the town. I never, ever take pictures through airplane windows, except for this time when I took about fifty. It cost US$144. Recommended, on a nice day. On a bad day, if the plane takes off at all the flight is probably unspeakable.

- Because, of course, I couldn’t bring fuel onto the airplanes. Nor could I bring bear spray, and bear spray in Skagway costs a fortune. While there are bears everywhere on the Chilkoot Trail, and over a five-day backpack sightings are virtually guaranteed, there has supposedly never been a bear attack in the history of the park. Use your discretion.

- Logistical tip. There are two official ways to get out of Bennett: the profligate can charter a seaplane, while most people book the White Pass and Yukon Route’s Chilkoot service to Skagway, Whitehorse, or points in-between. The train is great, by all means do that, but be sure to pick up your ticket from the WPYR station near the Skagway waterfront. The confirmation they e-mail you is not your ticket. Your ticket will be handed to you by a nice lady at a ticket window who will remind you that the railway always operates on Alaska time even within the Pacific time zone. In my experience the WPYR’s customer service, even to smelly hikers, is superb, but do not forget this. It is in principle possible to hike out on the railroad’s right-of-way, returning south to meet the highway at Fraser, but it’s a long trip, technically illegal, devoid of facilities, full of bears, offers the prospect of being run over by a train, and not recommended unless you truly have no choice.

- At the moment I was writing these words at camp in Canyon City, a big black bear strolled down the opposite shore of the Taiya River, facing some dozen campsites, like she couldn’t imagine why anyone would be bothered. There would be more.

- A border crossing that, due to COVID-19 politics, has been closed since 2020. Mine was the last “class” of hikers that could do the whole Chilkoot Trail for three years and counting. If I’d missed out I’d have been really mad.

- During the Gold Rush, Skagway and Dyea were both under the control of notorious gangster “Soapy” Smith until he was gunned down on the Skagway wharves. The two towns had reasonable communication by small boat or, later, all-weather road, with Dyea leading over the Coast Mountains via the Chilkoot Pass and Skagway via the White Pass. The White Pass, being narrower and rockier, was worse to walk but had gentler grades, especially in the winter of the Gold Rush when prospectors could mostly go up the frozen Taiya River until the pass itself. Skagway also has a far superior harbour, while Dyea is approached through a mile or so of mud flats. As a result, the Chilkoot was a better choice for a prospector on foot but the White was much, much better for a railway, and when one was built between Skagway and Canada Dyea pretty much vanished. Resource work let Skagway hang on until the tourism boom of the late 20th century led to its current prosperity.

- Maybe this was just a coincidence but my “class” of Chilkoot Trail hikers was something like 70% female. Stampeders so desperate for companionship they proposed to curvy trees would be stunned to know that, in a century, the Golden Stairs would be literally crawling with women.

- Read the interpretive signs and learn that’s because it was, serving a sawmill that closed down in the ’50s.

- People do go over the pass in a day, or even trail-run the Chilkoot end-to-end as a day trip, but these are people with elite fitness and expertise who don’t need my advice.

- Parks Canada had started building a much larger, much more ornate hut perched on the edge of the pass, a beautiful, multi-storey structure that you can see for miles to the north. But on my visit it was strictly off-limits, and at Bennett I learned that a winter storm had hit it so hard it had been blown off its foundations and was likely to be condemned and entirely replaced. Beauty has its price.

- A clever idea by one of Parks Canada’s 2012 Chilkoot Trail artists-in-residence, Corrie Francis Parks, where you write a little note to yourself from the summit of the pass and a year later get a reminder in the mail of just how you felt at the moment of triumph. It’s less important when you keep a diary, but still cool. Not that you’re naturally at your most introspective after all that work; one hiker filled out her postcard with what she had for breakfast that morning. That said, as of the summer of 2022 I had not got mine, and I assume COVID-19 put paid to that as it did so many other things.

- Much simpler than the American model, self-serve, and pinned to a bulletin board where they can be safely ignored.

- Also self-serve; a stack of blanks, some pencil crayons, and a book on introductory calligraphy.